WEINBERG: Wir gratulieren! / Katia Guedes, sop (Madame); Anna Gütter, mez (Fradl); Olivia Saragossa, mez (Bejlja); Jeff Martin, ten (Reb Alter); Robert Elibay-Hartog, bar (Chaim); Kammerakademie Potsdam; Vladimir Stoupel, cond / Oehms Classics OC 990 (live: Konzerthaus Berlin, September 23, 2012)

I’ve always been a huge fan of Mieczysław Weinberg, but his opera about a newly-married woman aboard a ship who discloses that she was a prison guard at Auschwitz, The Passenger, has always struck me as way too dark, possibly because a childhood friend of mine was a prisoner in a concentration camp, but this one intrigued me because the plot is lighter. This recording, scheduled for release August 8, is the very first of this work.

Based on a story by famed Jewish writer Sholom Aleichem (1859-1916), whose story of Tevye the Dairyman became the basis of Fiddler on the Roof, Wir gartulieren (which translates into Contratulations in English or Mazel Tov in Yiddish) is a much lighter story. Written in 1975-82 and premiered in 1986, Weinberg had to include some extraneous praise of Communism against capitalism in his libretto, but otherwise it is based on Aleichem’s story. The plot is as follows:

In the rich home of a Jewish lady in Odessa at the turn of the last century, Bejlja the cook is busy preparing a festive dinner in the kitchen, because the engagement of the daughter of the house is imminent. The widowed cook complains of her laborious work and her lonely life without a husband. A book distributor appears with new books, and Bejlja gives him food and drink. She entrusts him with the latest gossip about her life. With every glass he empties, the bookseller becomes more talkative: first, he advertises his socialist books, shortly afterwards suggesting to Bejlja to found a community with him in view of her savings. Chaim, the neighbor’s servant, comes in and begins to blaspheme about this. Finally Fradl the maid, with a funny little song on the lips, appears in the kitchen. Chaim, who was initially hiding from her, comes out and starts flirting violently with the maid. An exuberant celebration and drink begins, and when the mood reaches its peak, Bejlja and the book distributor decide to quit their service and become engaged. In high spirits, the book distributor reads particularly beautiful passages from the books he brought with him. Inspired by the happiness of the newlyweds, Chaim suggests a wedding shower and then spontaneously turns to Fradl with a marriage proposal, which she finally accepts after initially resisting. Surprisingly, the lady of the house appears and stops the joyful singing and joking.

This performance, given in German rather than Russian, and the score has been reduced from a full ensemble to a chamber orchestra, but the flavor of the music is kept intact. Those readers familiar with Weinberg’s music will understand what I mean when I say that, despite its comic bent, the music is not entirely or consistently “comical” in the sense that Italian comic operas, or older German ones like The Merry Wives of Windsor or Martha, are. Weinberg was much more intent on writing continuous musical lines that change and morph to match the words; when the words are not particularly funny, neither is the music, but when they are his music is lively and energetic—but, again, not in a really conventional manner. His deep interest in and admiration for the music of Stravinsky, Bartók and Shostakovich led him to create music with vacillating minor and major keys and quite a few passages of bitonality. Let us say, then, that the opera is humorous in an amusing way but not something that will make you laugh out loud, and there are, of course, numerous touches taken from Jewish folk and even liturgical music throughout the score.

This live performance was given at at the Konzerthaus Berlin on September 23 2012. (The photo from this production is reproduced here.) A German-only libretto is included in the booklet, which puts us English-speakers at a disadvantage; as a favor to my readers, I am including an English translation of the libretto HERE. Oehms Classics, in keeping with most record companies nowadays, also doesn’t seem to think that identifying the voice range of the singers on the back cover matters, so I had to spend 10 minutes searching the net to find out what range these singers’ voices were. (Note: The booklet, which came to me after I wrote most of the review, does identify the singers’ voice ranges–in the back). All the female singers have solid, bright voices, and tenor Jeff Martin has a compact, brilliant timbre that reminded me of Mark Panuccio. This is particularly good news since the bookseller gets the lion’s share of the singing in this relatively short work.

This live performance was given at at the Konzerthaus Berlin on September 23 2012. (The photo from this production is reproduced here.) A German-only libretto is included in the booklet, which puts us English-speakers at a disadvantage; as a favor to my readers, I am including an English translation of the libretto HERE. Oehms Classics, in keeping with most record companies nowadays, also doesn’t seem to think that identifying the voice range of the singers on the back cover matters, so I had to spend 10 minutes searching the net to find out what range these singers’ voices were. (Note: The booklet, which came to me after I wrote most of the review, does identify the singers’ voice ranges–in the back). All the female singers have solid, bright voices, and tenor Jeff Martin has a compact, brilliant timbre that reminded me of Mark Panuccio. This is particularly good news since the bookseller gets the lion’s share of the singing in this relatively short work.

The chamber orchestra reduction doesn’t seem to harm the music at all, since Weinberg seldom used thick textures even in his symphonies. Indeed, one of the hallmarks of his orchestral writing is a use of the orchestra almost as if it were a large chamber group, with an emphasis on the brass and winds playing either singly or in small choirs that play off each other. Like Wagner, however, he found a way to write continuous music that, although it includes solo monologues that one can identify as ariettas such as the bookseller’s “Guten Tag, ich will nicht stör’n, meine liebe Bejlja!” or Fradl’s “Hab geweint drei Bäche Tränen” in Act I, does not really have full arias that set off the singer for two or three minutes at a time while nothing of import is going on behind him or her. I actually like this, but I know a few opera lovers who will complain that “the music never gets started” because unless one has a discernible pumping rhythm and set arias, music like this doesn’t really strike them as being “operatic.” There’s also a very nice quartet for the three female singers and the baritone at the end of Act I, but again, it’s short and doesn’t linger any longer than the lyrics and the dramatic situation call for. And the first act ends quietly, stopping on a dime. Surely this is not Good Opera!…except that it is, because that’s what the situation calls for.

Surprisingly, Act II opens with a very lively (for Weinberg) little dance in an odd meter played mostly by trumpets and winds, albeit with a violin cadenza that comes out of nowhere. It’s not overly jocular music, but if you’re a good musician you’ll have a chuckle at the way he handles it. Not too far into this act is a rather jocular but bitonal tenor-soprano duet (“Verlobung”) that eventually evolves into a real melody that conventional opera-lovers can enjoy (if they don’t mind the stiffish rhythms played by biting, Stravinskian winds behind the singers). Again, however, I can only go by the general plot description since I don’t have a libretto. The bookseller (Reb Alter) also has a fairly bouncy, Yiddish-sounding arietta, “Zu hause waren wir zehn,” which evolves into a trio with two of the ladies and then a quartet with the baritone. The music morphs and evolves, changing its melody and slowly increasing the tempo, eventually turning into a bitonal hora. What a wonderful piece! When “Madame” comes in to stop the revelry, she sounds like a screeching shrew—and I mean that literally, with high notes that will make the fillings in your teeth ache—but this may possibly be intentional. After all, she is a party pooper.

My sole complaint of this release is that Oehms Classics chose to stretch it over two CDs, which runs the price up, whereas at 80:23 it fits comfortably onto one CD. (Even I can burn CDs as long as 81:20 with Nero.) Still, this is clearly a must-have for Weinberg collectors and even a work to investigate for those who may not normally like his heavier, often sadder music. I would encourage other opera houses to perform it but, as a somewhat short opera and a comic one at that, I can’t think of too many other works one would pair with it save Ravel’s L’Entant et les Sotrileges.

—© 2020 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter (@Artmusiclounge) or Facebook (as Monique Musique)

Return to homepage OR

Read The Penguin’s Girlfriend’s Guide to Classical Music

This live performance was given at at the Konzerthaus Berlin on September 23 2012. (The photo from this production is reproduced here.) A German-only libretto is included in the booklet, which puts us English-speakers at a disadvantage; as a favor to my readers, I am including an English translation of the libretto

This live performance was given at at the Konzerthaus Berlin on September 23 2012. (The photo from this production is reproduced here.) A German-only libretto is included in the booklet, which puts us English-speakers at a disadvantage; as a favor to my readers, I am including an English translation of the libretto

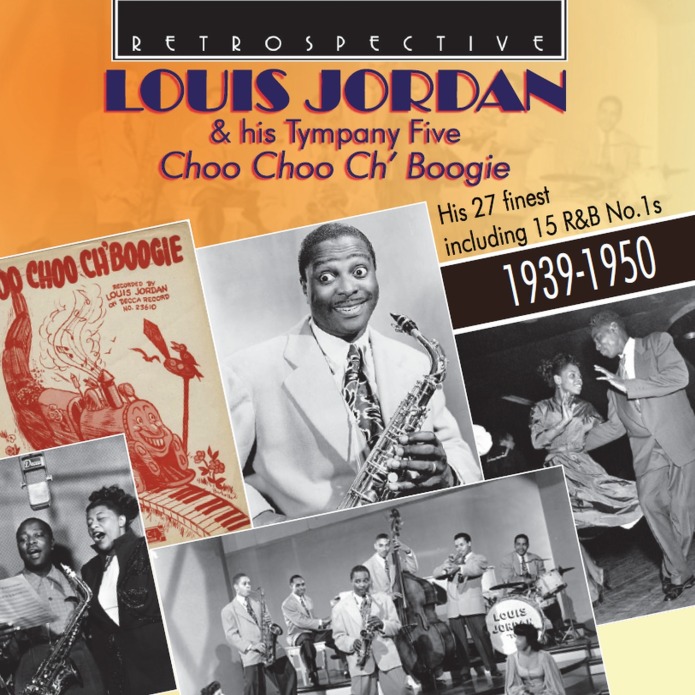

But Chick Webb and Ella weren’t the only two jazz artists to take the rather funny jazz songs of Jordan seriously. Woody Herman’s first Herd recorded cover versions of Don’t Worry ‘Bout That Mule and Caldonia, the latter becoming as big a hit for Herman as it had been for Jordan—a million-selling record, at #1 on the R&B charts for seven weeks and a #6 pop hit. Dave Dexter Jr., publicity director of rival Capitol Records, wrote the lyrics for another of Jordan’s biggest hits, Buzz Me Blues. Although I purposely did not list the exact personnel for these recording sessions in the header, the musicians in his group—sometimes a quintet as advertised, sometimes a sextet and sometimes a septet—included such bonafide jazz musicians as pianist Wild Bill Davis, bassist Al Morgan, former Fats Waller drummer Slick Jones and trumpeter Idrees Sulieman, who played on several of Thelonious Monk’s early Blue Note recordings. And Jordan himself played very good, if not exceptional, short jazz solos on several of his records.

But Chick Webb and Ella weren’t the only two jazz artists to take the rather funny jazz songs of Jordan seriously. Woody Herman’s first Herd recorded cover versions of Don’t Worry ‘Bout That Mule and Caldonia, the latter becoming as big a hit for Herman as it had been for Jordan—a million-selling record, at #1 on the R&B charts for seven weeks and a #6 pop hit. Dave Dexter Jr., publicity director of rival Capitol Records, wrote the lyrics for another of Jordan’s biggest hits, Buzz Me Blues. Although I purposely did not list the exact personnel for these recording sessions in the header, the musicians in his group—sometimes a quintet as advertised, sometimes a sextet and sometimes a septet—included such bonafide jazz musicians as pianist Wild Bill Davis, bassist Al Morgan, former Fats Waller drummer Slick Jones and trumpeter Idrees Sulieman, who played on several of Thelonious Monk’s early Blue Note recordings. And Jordan himself played very good, if not exceptional, short jazz solos on several of his records. For all its hard-driving R&B beat, Five Guys Named Moe is, in the instrumental break, as exciting a ‘40s jazz record as you’re likely to hear, and in several records one is impressed by the trumpet solos of the little-known Courtney Williams (1939), Eddie Roane (1942-44) and Aaron Izenhall (July 1945, replacing Sulieman, through 1950). Personally speaking, despite my admiration of Bing Crosby as a laid-back, jazzy-styled singer, I thought that My Baby Said “Yes” was a real stinker of a song. It’s also too much Bing and not enough Louis. Of the three duets with Ella Fitzgerald, Stone Cold Dead in the Market is the funniest but most pop-oriented, Petootie Pie has some good scat singing by Ella, and Baby It’s Cold Outside (now considered a taboo song because the feminists think it involves date rape) is excellent, a more swinging alternative to the more famous recording by Dinah Shore and Buddy Clark. Jordan also recorded two duets with the lesser-known but bluesy-styled Martha Davis (Daddy-O, which hit #7 on the R&B charts, b/w You’re on the Right Track Baby). Possibly the most R&R-like song on the album is Ain’t That Just Like a Woman (including a very rock-music-like guitar solo by Carl Hogan), one song I had never heard before. The lyrics of the Tommy Edwards-Jimmy Hilliard hit That Chick’s Too Young to Fry are definitely wrapped up tightly in double entendre. Early in the Mornin’ is an early example of Calypso beat. We end this retrospective with another record I hadn’s heard before, I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead (You Rascal You) with the great Louis Armstrong, and yes, Louis does play the trumpet in addition to singing–and quite well, too.

For all its hard-driving R&B beat, Five Guys Named Moe is, in the instrumental break, as exciting a ‘40s jazz record as you’re likely to hear, and in several records one is impressed by the trumpet solos of the little-known Courtney Williams (1939), Eddie Roane (1942-44) and Aaron Izenhall (July 1945, replacing Sulieman, through 1950). Personally speaking, despite my admiration of Bing Crosby as a laid-back, jazzy-styled singer, I thought that My Baby Said “Yes” was a real stinker of a song. It’s also too much Bing and not enough Louis. Of the three duets with Ella Fitzgerald, Stone Cold Dead in the Market is the funniest but most pop-oriented, Petootie Pie has some good scat singing by Ella, and Baby It’s Cold Outside (now considered a taboo song because the feminists think it involves date rape) is excellent, a more swinging alternative to the more famous recording by Dinah Shore and Buddy Clark. Jordan also recorded two duets with the lesser-known but bluesy-styled Martha Davis (Daddy-O, which hit #7 on the R&B charts, b/w You’re on the Right Track Baby). Possibly the most R&R-like song on the album is Ain’t That Just Like a Woman (including a very rock-music-like guitar solo by Carl Hogan), one song I had never heard before. The lyrics of the Tommy Edwards-Jimmy Hilliard hit That Chick’s Too Young to Fry are definitely wrapped up tightly in double entendre. Early in the Mornin’ is an early example of Calypso beat. We end this retrospective with another record I hadn’s heard before, I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead (You Rascal You) with the great Louis Armstrong, and yes, Louis does play the trumpet in addition to singing–and quite well, too.

Stone has an exceptionally warm, rich voice with excellent diction and an exceptional range from the top baritone notes (G# and A) down to a somewhat Lawrence Tibbett-like low range. Listening to him in this recital, it’s difficult to imagine why he hasn’t sung in America at the Metropolitan and San Francisco Opera Companies; he’s that good. The only thing I can’t judge from this song recital is his power of expression in opera; Ireland’s songs are lyrical and melodic but entirely lacking in drama. They rather go in one ear and out the other except for the fact that Stone is singing them. At the end of “I Will Walk on the Earth,” he cuts loose with a ringing high G of exceptional quality. His accompanist, pianist Sholto Kynoch, is also outstanding throughout this recital.

Stone has an exceptionally warm, rich voice with excellent diction and an exceptional range from the top baritone notes (G# and A) down to a somewhat Lawrence Tibbett-like low range. Listening to him in this recital, it’s difficult to imagine why he hasn’t sung in America at the Metropolitan and San Francisco Opera Companies; he’s that good. The only thing I can’t judge from this song recital is his power of expression in opera; Ireland’s songs are lyrical and melodic but entirely lacking in drama. They rather go in one ear and out the other except for the fact that Stone is singing them. At the end of “I Will Walk on the Earth,” he cuts loose with a ringing high G of exceptional quality. His accompanist, pianist Sholto Kynoch, is also outstanding throughout this recital.