SHAPIRO PERFORMS SCHUBERT, Vol. 1 / Talks regarding Schubert’s accompaniments, horn sounds, aspects of performance and notation. Sonata in B, D. 575. Sonata in C, D. 840, “La Reliquie.” Sonata in a minor, D. 845. Sonata in D, D. 850. / Daniel Shapiro, piano / RPS Classics 0010241 (DVD)

SHAPIRO PERFORMS SCHUBERT, Vol. 2 / Sonata in A, D. 664. Sonata in a minor, D. 537. Sonata in G, D. 894. Sonata in c minor, D. 958. Hungarian Melody in b minor, D. 817 / Daniel Shapiro, piano / RPS Classics 0010242 (DVD)

SHAPIRO PERFORMS SCHUBERT, Vol. 3 / Sonata in a minor, D. 784. Sonata in A, D. 959. Sonata in B-flat, D. 960. Moment Musicaux No. 2 in A-flat, D. 780 / Daniel Shapiro, piano / RPS Classics 0010243 (DVD) All three DVDs available at Amazon.com and from the artist’s website (www.danielshapiropianist.com)

Also available on 5 conventional CDs from the artist’s website for $15 per disc, distributed as follows:

Vol. 1 – Sonatas in B (D. 575), A (D. 664) & c minor (D. 958), Moment Musicaux No. 2

Vol. 2 – Sonatas in a minor (D. 537) & D (D. 850)

Vol. 3 – Sonatas in a minor (D. 845) & G (D. 894)

Vol. 4 – Sonatas in C (D. 840) & A (D. 959)

Vol. 5 – Sonatas in a minor (D. 784) & B-flat Major (D. 960)

Daniel Shapiro is a pianist who specializes in music of the Romantic Era, specifically that of Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann and Brahms, and also teaches at the Cleveland Institute of Music. As a chamber musician, he has performed regularly with members of the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony and L.A. Philharmonic as well as with the Cavani, Mirò and Linden String Quartets, and has performed as piano soloist with the National Symphony, São Paulo State Symphony, Academy of London, Knoxville Symphony and Los Angeles Debut Orchestra. He was the top prize winner of a William Kapell competition as well as winner of the American Pianists’ Association Beethoven Fellowship Award.

This three-DVD/five-CD set includes 11 of Schubert’s 15 piano sonatas, and I believe that Shapiro was wise to eliminate the earliest ones on musical grounds. The first two sonatas are youthful works and in many ways truncated (like Beethoven’s minuscule Op. 49 sonatas) or, in the case of the D. 279, unfinished, as are the sonatas D. 557 (it has never been proven that the third movement published with this sonata, in E flat, is really the finale of the work) and 566. Since Schubert was moving towards an entirely new concept of the piano sonata, very different from Beethoven’s, hearing these early pieces, in my view, is more of a hindrance than a help. The earliest work presented here is the Sonata in a minor, D. 537, written in 1817 when Schubert was 20 years old.

His set of the Schubert sonatas, like his set of the 32 Beethoven sonatas, is quite obviously a labor of love. You can access his complete series of the Beethoven works for free on YouTube, but he has packaged and is selling the Schubert series. It’s a wise move for two reasons: 1) There simply aren’t that many extensive series of the Schubert sonatas out there, and 2) the DVDs include wonderful talks by Shapiro on the shape and sound of Schubert’s sonatas as well as aspects of the composer’s notation. Some of his examples are not from the sonatas: he also plays, for instance, the famous cello theme in the first movement of the String Quintet in C, the opening song of Winterreise as well as other works, to illustrate how Schubert seemed to be “receiving” music rather than “composing” it. One thing that strikes the listener immediately (it certainly struck me) is Shapiro’s remarkable sense of touch. In his hands, the piano seems less of a percussion instrument than one of softness and richness of sound; it almost strikes the ear as if the piano is playing itself. This is not, however, to imply that Shapiro cannot play with strength when called upon, simply that when he does play with strength, it sounds like his softer playing simply increased in volume. (I know this is a difficult concept to convey in words, but when you hear him play you’ll know what I mean.)

And this, as it turns out, is absolutely perfect for Schubert. His sonatas are not music that react well to strict, powerful performances, as those of Mozart and Beethoven do. Think of his String Quintet in C as a chamber work compared to, say, any of Beethoven’s string quartets or quintets. Beethoven at his most lyrical still has a strong rhythmic element (one critic said that you can often recall major Beethoven works strictly by beating out their rhythmic pattern without a melody), whereas even Schubert at his most dramatic always has a strong element of lyricism. This is particularly clear in the section where Shapiro discusses Schubert’s “dark side,” his premonitions of death or insanity, expressed via sharp shards of music in minor keys (perhaps the most famous examples being Erlkönig or the orchestral outbursts in the “Unfinished” Symphony). This fits in with what I’ve always read about Schubert, than he considered life a journey in which we, as wanderers, fumble about as we move from the bucolic to the violent, often without warning—a philosophy perhaps best summarized in his magnificent “Wanderer Fantasy.” Because of this, Shapiro believes that one must “play Schubert’s music with a sense of inevitability, and yet at the same time with a sense of imagination.”

These talks, then, and the musical illustrations played within them, indicate what we are going to hear in his performances of the sonatas. Gone are the surface excitement and tensile strength one heard in the Schubert sonata performances of Artur Schnabel, Clara Haskil and Sviatoslav Richter (the latter of which, for my taste, was usually too strong in his approach). The quicksilver playing of Haskil is a specific case in point. Note, here, the difference in timing between her performances of the D. 845 and D. 960 sonatas as compared to Shapiro’s:

| Haskil | Shapiro | |

| Sonata D. 845, 1 | 7:52 | 9:46 |

| Sonata D. 845, 2 | 7:28 | 12:26 |

| Sonata D. 845, 3 | 4:54 | 7:30 |

| Sonata D. 845, 4 | 4:17 | 4:58 |

| Sonata D. 960, 1 | 13:15 | 15:09 |

| Sonata D. 960, 2 | 7:31 | 11:26 |

| Sonata D. 960, 3 | 3:36 | 4:21 |

| Sonata D. 960, 4 | 7:42 | 8:32 |

Nor is this simply a matter of playing faster. Haskil, being Rumanian, shared with other Rumanian and Hungarian pianists (and conductors, and singers) a sense of musical urgency in performance—think of Dinu Lipatti, one of her closest friends, for instance, who even played Chopin with a wide-awake, less dreamy-eyed sense of style. The architecture of the music was what mattered, and it was her duty, as she saw it, to bring that structure to the fore. (Refer to my recent post on conductor Michael Gielen who, although Austrian and not Eastern European, took a similar approach to orchestral music, even in Schubert.) There is something to be said for both approaches, but to my ears Haskil rushed the Andante movements a bit too much, though her Scherzo and Rondo allegros were vivacious and wonderful. She also had a superb keyboard touch which allowed her to evoke feelings in the music even at brisker speeds.

Shapiro is more leisurely and ruminative. There is a considerable amount of “space” here and there between notes and chords; he doesn’t view these sonatas in a strictly structural manner, but more as sensatory discovery. Yet in some cases it seems to me that his longer timings are due to additional repeats being observed, not just a brisker pace. Still, it is clear that he makes more of a contrast between, for instance, the opening motif of the forst movement of D. 845 and its brisk main melody, and he returns to this slower pace for the transition figures. This gives an entirely different feel to the music, one that has urgency in places and a stop-and-smell-the-roses feeling in others.

The venue in which the sonatas were taped is obviously a church—one can see the huge organ pipes directly behind Shapiro’s piano—but it is not identified. Nonetheless, the sound is natural and clear with enough natural “space” around the piano to make the sustained chords sing. Watching Shapiro play, one gains the sense that he is completely immersed in the music. His body leans forward towards the soundboard of the piano, then leans back; he often shakes his head as he plays the stronger and busier figures. The camera takes in different angles but most of the time shows his hands on the keyboard, which is what most people are interested in seeing. Close-ups reveal his playing method, a from-the-top approach, sometimes raising the hands entirely off the piano but more often a deep-in-the-keys touch that gives his playing richness. (The camera seldom shows his feet, a rare exception being between 14:09 and 14:40 in the Sonata D. 575, so I could only gauge his pedaling effects by aural means.) Ordinarily I’m not a huge fan of watching classical performers (particularly soloists) on video, but Shapiro is nearly as interesting to watch play the piano as Shura Cherkassky was, so I enjoyed the experience tremendously.

This musical ebb-and-flow continues throughout his playing of all eleven sonatas, but to be honest, if one is emotionally engaged in the listening process, as I was, you can only take one sonata at a time. It’s almost too draining to watch and listen to any of the three DVDs complete in one sitting. And although one is aware of an underlying structure in these sonatas, what one takes away from them is their symphonic aspect, and this is, I think, what many people who don’t like the Schubert sonatas (including my younger self) don’t fully understand. These works are simply not as tightly bound or follow a straight-line trajectory as do the Beethoven sonatas. Nowhere in them are those on-the-seat-of-your-chair moments like the juggernaut movements in Beethoven, and Shapiro’s more diffuse approach to the music sometimes removes that juggernaut feeling anyway (as, for instance, in the Scherzos). This is not an entirely bad thing, just different. One can enjoy Karl Böhm conducting Schubert just as much as Michael Gielen.

Shapiro thus is able to give greater weight and a richer tone to such words as the somewhat brief sonatas D, 575 and 840, each roughly 20 minutes in length. Interestingly, he injects a syncopated feeling into the first movement of the latter, making it almost sound like a Latin rhythm, something I’ve never noticed in others’ playing of this work. His deep-keys touch continues to delight one as well as add a richness to the proceedings. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that his sense of tone color is almost as great as that of the great organists like Marie-Claire Alain or Virgil Fox. At times I almost imagined him jumping up from his Steinway and playing the sonatas on the organ behind it.

The more Shapiro moves into the later sonatas, the more his approach not only makes sense but enriches one’s absorption of the music. I’m sure that he spent countless hours working out exactly what tempos and phrasing he wanted to use in every movement in each of these works, but the end result is so engaging that it almost sounds spontaneous, as if he himself is making up these sonatas, phrase by phrase, as he plays them. And to be honest, one’s familiarity with later piano works of similar thematic contrast and complexity—I’m thinking, specifically, of the works of Alkan, late Scrabin and Debussy, Ives, Griffes and even Sorabji—help one absorb and appreciate what Schubert did here. As I say, his structure is always there but is often buried beneath those long phrases and contrasting themes. Think of the String Quintet and how much it sounds like a symphony…one might almost say the same thing of Brahms’ Piano Quartets. One can easily conceive nearly any of these piano sonatas played by an orchestra and presented as a symphony. One cannot say the same thing of Beethoven’s sonatas—they sound like sonatas and nothing but.

In the last three sonatas, I compared Shapiro’s playing with that of Craig Sheppard (Roméo Records 7283-4), a modern-day pianist who also takes generally brisk tempos in Schubert. More to the point, Sheppard prefers a leaner sound profile than Shapiro—what I would characterize as a “Beethoven sound” (and Sheppard’s complete Beethoven sonata cycle is one of the most interesting issued on CD). He, too, also prefers a tauter trajectory of the musical material, with less relaxation, pauses or rhetorical phrasing than Shapiro. One thing you immediately notice if you compare Shapiro to Sheppard is the former’s much greater sense of coloration: he is able to produce an almost infinite variety of shades and tones. No two of his soft chords sound alike, and neither do most of his forte attacks. His playing has so much variety in it that it almost sounds like a duo-piano recital, with two keyboardists of contrasting skills, somehow magically combined in one man with only ten fingers. Indeed, the more one listens to Shapiro’s Schubert the more one is convinced that this is, if not the only way to play these sonatas, surely the best way. Since these sonatas tend, for the most part, to be quite long (the shortest of them are the D. 664 at 16:17 and D. 537 at 18:36; most of them are well over a half-hour in length), listeners need to come to them with a long attention span. Listening in sound bites will not do for Schubert.

I could go on and on about these videos, but don’t think it would add to my overall impression. I recommend the videos over the audio CDs because the CDs omit his interesting talking points and the performance of the Hungarian Melody in b minor—also, the three DVDs are less expensive than the five CDs. These are remarkable performances, deeply felt and played with conviction and purpose. There is nothing in Shapiro’s approach that could be called errant or uninteresting; it all reveals a unanimity of purpose that conveys a mind that has worked on and absorbed these works to the fullest.

— © 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Read my book: From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed history of the intersection of classical music and jazz

Does this mean that Gielen’s work is unlikable? Not at all. I find it fascinating because it is so different from anyone else’s. This is one reason why I prize his set of the Beethoven Symphonies on the SWR label as the finest of all stereo or digital recordings. He gives you the cleanliness of sound and attack that you hear, for instance, from David Zinman, but there is an extra dimension of emotion and feeling in Gielen’s work that marks him as a genius and not merely a time-beater.

Does this mean that Gielen’s work is unlikable? Not at all. I find it fascinating because it is so different from anyone else’s. This is one reason why I prize his set of the Beethoven Symphonies on the SWR label as the finest of all stereo or digital recordings. He gives you the cleanliness of sound and attack that you hear, for instance, from David Zinman, but there is an extra dimension of emotion and feeling in Gielen’s work that marks him as a genius and not merely a time-beater.

audiences, first gaining attention at the Howard Theatre in Washington for two weeks, then moving to the 63rd Street Theater in New York City in May before racking up 504 performances(!) at the Cort Theater on 48th Street. The cast included several names that would become famous over the next few years such as Adelaide Hall, Florence Mills (who replaced Gertrude Saunders after the first year), Fredi Washington and Paul Robeson—none of whom recorded anything from the show!—and a very young Josephine Baker in the chorus line. The big mistake Sissle and Blake made was trying to revive the show, twice in fact, in 1932 and 1952. The second time, they only got four performances in before the show closed, but ironically RCA Victor had already rushed to record four songs from the show and issued them on LP!

audiences, first gaining attention at the Howard Theatre in Washington for two weeks, then moving to the 63rd Street Theater in New York City in May before racking up 504 performances(!) at the Cort Theater on 48th Street. The cast included several names that would become famous over the next few years such as Adelaide Hall, Florence Mills (who replaced Gertrude Saunders after the first year), Fredi Washington and Paul Robeson—none of whom recorded anything from the show!—and a very young Josephine Baker in the chorus line. The big mistake Sissle and Blake made was trying to revive the show, twice in fact, in 1932 and 1952. The second time, they only got four performances in before the show closed, but ironically RCA Victor had already rushed to record four songs from the show and issued them on LP! And indeed, this is the virtue of hearing as many of the original recordings as possible. They capture an almost irrepressible energy force that is seldom heard in old records; the music jumps, cavorts and seduces all at the same time. Primary among the virtues of these recordings is the voice of Sissle himself, a high, bright tenor with superb diction, intonation and brio. With such a voice and his handsome good looks, Sissle could easily have become a superstar in the same vein as Al Jolson or Eddie Cantor had he not been black. Even more interestingly, Eubie Blake’s hot New York ragtime style is actually a lot closer to jazz (at least in rhythm if not in improvisation) than we may remember, particularly if you only heard him in his late years when he was the “old black darling” of TV and Broadway. Blake always maintained his enthusiasm of playing but the actual style, his continuity of phrasing, declined after the early 1960s.

And indeed, this is the virtue of hearing as many of the original recordings as possible. They capture an almost irrepressible energy force that is seldom heard in old records; the music jumps, cavorts and seduces all at the same time. Primary among the virtues of these recordings is the voice of Sissle himself, a high, bright tenor with superb diction, intonation and brio. With such a voice and his handsome good looks, Sissle could easily have become a superstar in the same vein as Al Jolson or Eddie Cantor had he not been black. Even more interestingly, Eubie Blake’s hot New York ragtime style is actually a lot closer to jazz (at least in rhythm if not in improvisation) than we may remember, particularly if you only heard him in his late years when he was the “old black darling” of TV and Broadway. Blake always maintained his enthusiasm of playing but the actual style, his continuity of phrasing, declined after the early 1960s. In the meantime, however, this CD is a pretty good indicator of what the show was like. One online critic complained about the juxtaposition of original recordings and later tapes made by Sissle and Blake in the 1950s (and two numbers, the Shuffle Along Medley and Love Will Find a Way, taped by Ivan Howard Browning and Eubie Blake in the early 1970s), claiming that hearing the modern recordings in context was “jarring.” I disagree to a point. Most of the Sissle-Blake tapes are extraordinarily lively, and in fact we hear in these some of Blake’s absolute best playing that was very, very close to the stride piano style of James P.Johnson. Yet I do miss some of those original recordings, not because I’m obsessed with old acoustic discs (I’m not) but because the flavor and energy in those original records is missing from most later recordings. Thus I would recommend the following additions and substitutions:

In the meantime, however, this CD is a pretty good indicator of what the show was like. One online critic complained about the juxtaposition of original recordings and later tapes made by Sissle and Blake in the 1950s (and two numbers, the Shuffle Along Medley and Love Will Find a Way, taped by Ivan Howard Browning and Eubie Blake in the early 1970s), claiming that hearing the modern recordings in context was “jarring.” I disagree to a point. Most of the Sissle-Blake tapes are extraordinarily lively, and in fact we hear in these some of Blake’s absolute best playing that was very, very close to the stride piano style of James P.Johnson. Yet I do miss some of those original recordings, not because I’m obsessed with old acoustic discs (I’m not) but because the flavor and energy in those original records is missing from most later recordings. Thus I would recommend the following additions and substitutions:

in 1991-92—an image is inserted here—but I’ve never heard it or even seen a review of it. (Kaplan also recorded Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 1 and Wieniawski’s Concerto No. 2, with Miller conducting, for the same label.) I can only imagine that he must have grown in this music over the years or he wouldn’t have insisted on re-recording it. Incidentally, this recording was made in 2011, so it apparently took a few years to get the nod for release.

in 1991-92—an image is inserted here—but I’ve never heard it or even seen a review of it. (Kaplan also recorded Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 1 and Wieniawski’s Concerto No. 2, with Miller conducting, for the same label.) I can only imagine that he must have grown in this music over the years or he wouldn’t have insisted on re-recording it. Incidentally, this recording was made in 2011, so it apparently took a few years to get the nod for release.

in John Fordham’s review in The Guardian as 77806. Williams himself e-mailed me to explain that the former title is the correct one, and that he is currently checking with the distributor to see if they can fix it online. The music itself is much more outré than the preceding tracks, in fact one of the most free-form things on the album. It almost sounds like Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz; I might even subtitle it Free Jazz, Jr. Even when a more “regular” pulse eventually arrives, it doesn’t remain really steady, but continues to fluctuate in a fluid manner—and once again, we hear that odd, piped-in sound of someone playing the strings of a piano with one’s fingers and, here and here, with light mallets. One of the more interesting things about this album is that, unlike Mingus’ bands, Williams is always audible but does not dominate the proceedings. In fact, he seems to take the position that his role is that of underpinning. As the composer of each piece, he clearly knows the structure from the ground up, but he steps back and allows the others to work in the foreground. Here Galvin switches to regular piano for his solo, but the odd tack-piano sound continues to weave its way along the right channel, providing a sort of surrealistic counterpoint to the proceedings. Nathoo’s sax solo here is a bevy of squawks and overblown notes, and once again it almost sounds as if the piece wraps up hurriedly.

in John Fordham’s review in The Guardian as 77806. Williams himself e-mailed me to explain that the former title is the correct one, and that he is currently checking with the distributor to see if they can fix it online. The music itself is much more outré than the preceding tracks, in fact one of the most free-form things on the album. It almost sounds like Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz; I might even subtitle it Free Jazz, Jr. Even when a more “regular” pulse eventually arrives, it doesn’t remain really steady, but continues to fluctuate in a fluid manner—and once again, we hear that odd, piped-in sound of someone playing the strings of a piano with one’s fingers and, here and here, with light mallets. One of the more interesting things about this album is that, unlike Mingus’ bands, Williams is always audible but does not dominate the proceedings. In fact, he seems to take the position that his role is that of underpinning. As the composer of each piece, he clearly knows the structure from the ground up, but he steps back and allows the others to work in the foreground. Here Galvin switches to regular piano for his solo, but the odd tack-piano sound continues to weave its way along the right channel, providing a sort of surrealistic counterpoint to the proceedings. Nathoo’s sax solo here is a bevy of squawks and overblown notes, and once again it almost sounds as if the piece wraps up hurriedly. cappella before the drums tastefully support him. Eventually Nathoo returns on tenor, this time in a lyrical, almost plaintive mood. The music becomes more lyrical in character even as the background rhythm continues to churn and play against the top line. Jurd’s trumpet is again abrasive in quality as she pits herself against the tenor sax, eventually prompting him to join her in a few angry phrases, then the Lonely Woman theme returns for a ride-out. One thing is becoming quite clear: as good as everyone in this band is, Jurd is an astonishing and creative musician, a real sparkplug who makes every track work better every time she involves herself in the proceedings.

cappella before the drums tastefully support him. Eventually Nathoo returns on tenor, this time in a lyrical, almost plaintive mood. The music becomes more lyrical in character even as the background rhythm continues to churn and play against the top line. Jurd’s trumpet is again abrasive in quality as she pits herself against the tenor sax, eventually prompting him to join her in a few angry phrases, then the Lonely Woman theme returns for a ride-out. One thing is becoming quite clear: as good as everyone in this band is, Jurd is an astonishing and creative musician, a real sparkplug who makes every track work better every time she involves herself in the proceedings. The drums shift the accents on the beat, however, and before long his continuing bass line is the only constant one can hang on to. A dead stop, following which is a slow, free-form passage played by Jurd and Nathoo; then Galvin enters on piano, his sound quirkily “phased” from right to left channel and back again via technological tinkering with the controls, followed by Jurd and Nathoo again. Then a very quiet free-form passage, with Nathoo noodling in the left channel and Jurd, now muted, in the right, with interjections from bass and drums. This increases in volume and intensity, and eventually tempo, as Galvin, Williams and Ibbetson get in on the action before another ritard, a dead stop, then a sluggish, out-of-tempo passage leading back to Williams’ initial bass line which eventually just hits a wall.

The drums shift the accents on the beat, however, and before long his continuing bass line is the only constant one can hang on to. A dead stop, following which is a slow, free-form passage played by Jurd and Nathoo; then Galvin enters on piano, his sound quirkily “phased” from right to left channel and back again via technological tinkering with the controls, followed by Jurd and Nathoo again. Then a very quiet free-form passage, with Nathoo noodling in the left channel and Jurd, now muted, in the right, with interjections from bass and drums. This increases in volume and intensity, and eventually tempo, as Galvin, Williams and Ibbetson get in on the action before another ritard, a dead stop, then a sluggish, out-of-tempo passage leading back to Williams’ initial bass line which eventually just hits a wall.

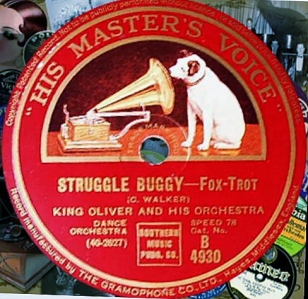

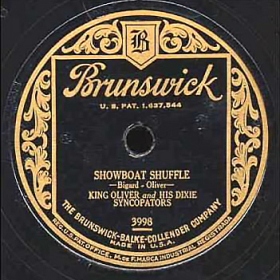

Eventually, I finally got around to the later recordings made by Oliver for the Victor (1929-30) and Brunswick (1928 and 1931) labels, when he was in residence at the Kentucky Club, and was absolutely bowled over. For here was a band based on New Orleans style that was clearly taking it several steps forward. The two-beat feel of New Orleans jazz was at times subjugated to a more streamlined 4/4 beat; and moreover, the beat the band played was by now far less “jerky” than you usually hear from 1920s bands, despite the continued presence of banjo and tuba in lieu of guitar and string bass. Listen to virtually any well known jazz orchestra of the late 1920s (except Duke Ellington, who was pretty much operating in an alternate universe), and what you hear is a rather “jerky” beat, over which hot and heavy soloists were continually trying to blow their brains out. Fletcher Henderson, Chick Webb, McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, Earl Hines, even Whiteman much of the time were all were stiff and jerky sounding. The same was true of Cab Calloway’s fledgling band that played the Cotton Club in the early ‘30s—but not so Oliver’s orchestra. They had a nice, rolling, loping beat that propelled the music without sounding klunky. And, more interestingly, they played first-class arrangements that still sound fresh and interesting, peppered with solos that likewise remain interesting nearly a century later. In short, this was a hell of a band. The only other contemporary orchestra that played in a style similar to theirs was that of white leader Isham Jones.

Eventually, I finally got around to the later recordings made by Oliver for the Victor (1929-30) and Brunswick (1928 and 1931) labels, when he was in residence at the Kentucky Club, and was absolutely bowled over. For here was a band based on New Orleans style that was clearly taking it several steps forward. The two-beat feel of New Orleans jazz was at times subjugated to a more streamlined 4/4 beat; and moreover, the beat the band played was by now far less “jerky” than you usually hear from 1920s bands, despite the continued presence of banjo and tuba in lieu of guitar and string bass. Listen to virtually any well known jazz orchestra of the late 1920s (except Duke Ellington, who was pretty much operating in an alternate universe), and what you hear is a rather “jerky” beat, over which hot and heavy soloists were continually trying to blow their brains out. Fletcher Henderson, Chick Webb, McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, Earl Hines, even Whiteman much of the time were all were stiff and jerky sounding. The same was true of Cab Calloway’s fledgling band that played the Cotton Club in the early ‘30s—but not so Oliver’s orchestra. They had a nice, rolling, loping beat that propelled the music without sounding klunky. And, more interestingly, they played first-class arrangements that still sound fresh and interesting, peppered with solos that likewise remain interesting nearly a century later. In short, this was a hell of a band. The only other contemporary orchestra that played in a style similar to theirs was that of white leader Isham Jones. To a certain extent, you might give credit—some of it, anyway—to Panamanian pianist Luis Russell, who was in the band for an extended period of time and perhaps set its style. He is heard on a large number of these Oliver discs, and although (as Morton pointed out) he wasn’t really a great jazz pianist, he was a first-class musician and knew his stuff. His most famous contribution to the Oliver orchestra was undoubtedly his modal composition Call of the Freaks, but many of the arrangements bear the stamp of his style and I get the feeling that much of what followed after he left was built around the principles he laid down.

To a certain extent, you might give credit—some of it, anyway—to Panamanian pianist Luis Russell, who was in the band for an extended period of time and perhaps set its style. He is heard on a large number of these Oliver discs, and although (as Morton pointed out) he wasn’t really a great jazz pianist, he was a first-class musician and knew his stuff. His most famous contribution to the Oliver orchestra was undoubtedly his modal composition Call of the Freaks, but many of the arrangements bear the stamp of his style and I get the feeling that much of what followed after he left was built around the principles he laid down. came at a time when Oliver was becoming less and less able to play the cornet himself, and a time when he was not doing well either financially or with the public. He had already made one band career decision after first arriving in New York in 1927 by disbanding in order to pick up freelance work for himself, but encroaching gum disease (caused, in part, by his lifelong habit of chewing sugar cane) eventually led him to hire other trumpeters once he re-formed his orchestra: Bubber Miley (before he went to Ellington), Louis Metcalf, Henry “Red” Allen, and eventually his nephew (some said his wife Stella’s nephew) Dave Nelson. Nelson became his strongest aide-de-camp, a sterling soloist and a spiritual sparkplug for a band that struggled to find an audience.

came at a time when Oliver was becoming less and less able to play the cornet himself, and a time when he was not doing well either financially or with the public. He had already made one band career decision after first arriving in New York in 1927 by disbanding in order to pick up freelance work for himself, but encroaching gum disease (caused, in part, by his lifelong habit of chewing sugar cane) eventually led him to hire other trumpeters once he re-formed his orchestra: Bubber Miley (before he went to Ellington), Louis Metcalf, Henry “Red” Allen, and eventually his nephew (some said his wife Stella’s nephew) Dave Nelson. Nelson became his strongest aide-de-camp, a sterling soloist and a spiritual sparkplug for a band that struggled to find an audience. radio broadcasts into account, something that Ellington, and his manager Irving Mills, did not overlook. The result was that Ellington’s fame grew while Oliver’s diminished. Later he was hired by the Savoy Ballroom before Chick Webb took up residence, but was unsatisfied with the pay. He tried to wangle more money out of management, but the end result was that he lost the job. Webb moved in as Oliver finally just gave up and moved back to Savannah, Georgia, where he died prematurely in 1938, a month before his 53rd birthday. He spent his last years working as a janitor, cleaning floors and toilets—unable to convince the people he worked with that he had once been a major jazz star with his own band and the discoverer of Louis Armstrong. After he left New York, Nelson took over the band, renaming it “The King’s Men,” but without the magical Oliver name it didn’t last. This, too, was a shame, because Nelson was a wonderful, incisive trumpeter and deserved better.

radio broadcasts into account, something that Ellington, and his manager Irving Mills, did not overlook. The result was that Ellington’s fame grew while Oliver’s diminished. Later he was hired by the Savoy Ballroom before Chick Webb took up residence, but was unsatisfied with the pay. He tried to wangle more money out of management, but the end result was that he lost the job. Webb moved in as Oliver finally just gave up and moved back to Savannah, Georgia, where he died prematurely in 1938, a month before his 53rd birthday. He spent his last years working as a janitor, cleaning floors and toilets—unable to convince the people he worked with that he had once been a major jazz star with his own band and the discoverer of Louis Armstrong. After he left New York, Nelson took over the band, renaming it “The King’s Men,” but without the magical Oliver name it didn’t last. This, too, was a shame, because Nelson was a wonderful, incisive trumpeter and deserved better. Everything, to be rather drippy—but I’m sure that at least part of Oliver’s audience liked this kind of music which is why he played and recorded it. For the most part, however, these recordings are something very little ‘20s jazz is: delightful to listen to. Two or three tracks in, and you don’t even really notice the banjo and tuba so much, except when the latter takes a break or a short solo. And the other musicians, as I noted, all sound wonderfully relaxed and inventive: not only Nelson (and Oliver on those rare occasions when he could still play) but trombonist Jimmy Archey (or J.C. Higginmotham on a few sides), clarinetist Hilton Jefferson, saxists Charlie Holmes and Charles Frazier, pianists Russell, Don Frye and Hank Duncan and even the occasional drum solos. Everyone sounds unfettered, relaxed and swinging.

Everything, to be rather drippy—but I’m sure that at least part of Oliver’s audience liked this kind of music which is why he played and recorded it. For the most part, however, these recordings are something very little ‘20s jazz is: delightful to listen to. Two or three tracks in, and you don’t even really notice the banjo and tuba so much, except when the latter takes a break or a short solo. And the other musicians, as I noted, all sound wonderfully relaxed and inventive: not only Nelson (and Oliver on those rare occasions when he could still play) but trombonist Jimmy Archey (or J.C. Higginmotham on a few sides), clarinetist Hilton Jefferson, saxists Charlie Holmes and Charles Frazier, pianists Russell, Don Frye and Hank Duncan and even the occasional drum solos. Everyone sounds unfettered, relaxed and swinging.