SCHMIDT: Symphonies Nos. 1-4. Notre Dame: Intermezzo / Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orch.; Paavo Järvi, cond / Deutsche Grammophon 00289 483 8336

This review is a story of two underrated classical musicians: the composer Franz Schmidt, who until a quarter-century ago was known only for one work, The Book of the Seven Seals (to be reviewed next), and conductor Paavo Järvi, of whom I took a dim view when he was music director of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. I listened to three of his broadcasts with the orchestra, including one in which he performed the Beethoven Ninth, and was utterly dissatisfied by his glib, surfacy readings—technically flawless but lacking any feeling or character. Yet in the years since he left Cincinnati, I’ve been impressed by a couple of his recordings made with European orchestras, so I decided to give this set a try.

And I’m glad I did, because it’s terrific: better than the one his father, Neeme Järvi, made for Chandos or the one that Vassily Sinaisky made for Naxos (although the Sinaisky performances are better than Pop Järvi’s).

But – who was Franz Schmidt, and why was he dismissed for decades? It’s a long story, but I’ll give you the Cliff Notes version here. (I almost wrote Reader’s Digest version, but the current version of this magazine is more of a handy help tips rag for homemakers and bears little resemblance to the one we boomers grew up with.)

Schmidt, who was Austro-Hungarian, was born in Pressburg, Hungary, which is now Bratislava a few days before Christmas 1874. His mother was an excellent pianist who was a pupil of Liszt; Franz later said she was the best piano teacher he ever had. He then studied piano with Rudolf Mader; also an organist, Mader taught him that instrument as well. But young Schmidt seemed to have been born under an unlucky star. In between his studies with Mader and entering the Vienna Conservatory, he took lessons with the well-known pedagogue Theodore Leschatitzky, who Schmidt found to be musically lacking and demeaning. When he finally got into the Vienna Conservatory, Schmidt was told that he had to study a second instrument in addition to music theory and counterpoint, so he chose the cello and became highly proficient on it. Schmidt originally studied theory with Anton Bruckner, but illness forced Bruckner to stop teaching and he was transferred to the class of Robert Fuchs, who was a proponent of Brahms. Unfortunately, Schmidt didn’t like Brahms’ music, so he left Fuchs’ class at the end of the year and studied privately while half-heartedly continuing his cello studies.

Schmidt auditioned for and won a position as cellist with the Vienna Court Opera Orchestra, which was a pretty ragged organization until Gustav Mahler arrived and put things into shape. Impressed with Fuchs’ playing, Mahler made him first cellist of the orchestra, but in time there was a falling out between the two when Mahler discovered that Schmidt disliked his music even more than he did Brahms’ (he called Mahler’s symphonies “cheap novels”). This, however, should not be construed as a racist comment. Remember that Schmidt detested Brahms’ music, too, and until the 1960s most of the world’s great conductors, except for Mahler’s acolytes Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer, either avoided Mahler’s symphonies completely or only conducted one or two works. But this attitude led to Schmidt’s playing being demeaned not only by Mahler but also by his acolyte Bruno Walter. Schmidt ceded his post as first cellist but stayed in the orchestra for several more years, during which time he wrote his first symphony as well as the opera Notre Dame, which Mahler originally promised to perform but never did.

By that time, too, Schmidt managed to obtain a position teaching cello until 1908 at the Conservatory of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, and from 1914 as professor of piano at what was now the Vienna Academy for Music and Performing Arts. In 1918 he began teaching composition at the Staatsakademie, where one of his pupils was future tenor Julius Patzak. All of these positions eventually let him leave the orchestra and concentrate on composition.

Bad luck somehow continued to hound him. In 1919, for an unexplained reason, his wife went mad and had to be institutionalized. Unlike his older colleague Richard Strauss, Schmidt had a low-key personality, was not a self-promoter and suffered bouts of depression and ill health. One of the few times his work was recognized was in 1928, when he submitted his Third Symphony to an international competition sponsored by the Gramophone Company which was celebrating the 100th anniversary of Franz Schubert’s death that year. Schmidt, however, did not win the top prize which was a large sum of money; that went to Kurt Atterburg. Instead, he was given a lip-service consolation prize for the “best new Austrian composition.”

Then more bad luck, His daughter, who married in 1929, died in childbirth two years later, This threw him into the depths of depression. He gave up composing for several years, turning to religion for comfort. That is when he read the utterly irrational Book of Revelations and began work on what is considered his masterpiece, The Book with Seven Seals (Das Buch mit Sieben Siegeln). Sometime during this period, he also wrote his fourth and last symphony, which many consider to be his greatest.

So here was Schmidt, finally recovered from his deep depression and being creative again, when in early 1938 here came Adolf Hitler and the Nazis to take over Austria. When Hitler discovered Schmidt and realized that he had been, however briefly, a pupil of his beloved Bruckner, he and Goebbels made a big fuss of him, publicly lauding him as the “greatest living Aryan symphonist” (not that Schmidt had much competition at the time), putting him in a newsreel, and commissioning a cantata from him to praise Hitler and the Nazis. Schmidt began working on this cantata but his heart wasn’t really in it, so he turned to other projects, but knowing that if he didn’t write it he might be sent to a concentration camp, he kept working on it but didn’t finish it before he suddenly died in 1939. This was Die deutsche Auferstehung, a piece that celebrated Austro-German unification. As Lani Spahr wrote in the liner notes for the reissue of Das Buch mit Sieben Siegeln, Schmidt was never a proponent of Nazi ideology: “The worst that can be said is that he was politically naïve.” And yet for many people, Richard Strauss got a free pass for his taking over conducting posts when protesting music directors walked out of Germany, or being so complicit with the Nazis that he also wrote pieces celebrating their allies, such as the Japanese Festmusik (which he also recorded for Deutsche Grammophon).

Even more info has come out on Schmidt since: that he had his composition pupils study Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, that he helped Jewish students get out of Austria after the Nazi takeover, and that although Schmidt himself was not a Nazi, his young second wife Marguerite was. Perhaps this is the reason one eyewitness saw Schmidt once give the Nazi salute in public.

Thus poor Schmidt was kicked to the curb, particularly when, after his death, the Nazis put up a large plaque honoring him (see below)—but that didn’t stop them from sending his insane first wife to be gassed in 1943.

I know this seems like a terribly long opening to this review, yet I think it necessary in order to explain at least one reason why his music wasn’t played for decades after his death. The other reason, of course, is that his harmonic language, while extremely interesting, was already considered passé by the time he died. All of which is a shame because each of his four symphonies had a different character, and the music, though written in a late-Romantic style, is exceptionally good.

In fact his first symphony, which premiered in 1902 with the composer conducting, received high praise from the critics—the same critics who also lambasted Mahler’s symphonies, which did nothing to help his relationship with the orchestra’s director. Despite Schmidt’s disdain for Brahms, there are some touches of that composer in this work although it also leans towards Wagner (lots of loud French horns and thick orchestral scoring) and his teacher Bruckner. Yet the first movement, in particular, is even more memorably melodic than Brahms or Bruckner. During the first full orchestral peroration, some of the violins are feverishly playing string tremolos behind the mass of sound, followed by a bit of Richard Strauss-like themes. But Schmidt was a superb craftsman, and he weaves all of these influences together into a smooth and unified narrative. And I have to say, the Frankfurt orchestra plays their hearts out in this symphony, thus I would think that they, at least, appreciated Schmidt’s music even if there are still music critics who find it second-rate. I don’t. This music is simply bursting with interesting and novel ideas; Schmidt obviously had a talent for blending his inspiration with a high level of craft. But of course it is exactly this unified form that contemporary critics (and most conductors) did not find in Mahler’s episodic sonic landscapes, which were all over the place in terms of themes, meters and tempi. Although their methods and results were different, Mahler shared with Berlioz the dubious distinction of being the most misunderstood composer of his time and, if anything, it took much longer (70 years as compared to nearly 40) after their deaths for Berlioz to become a mainstream composer than it did for Mahler.

Yet although Schmidt’s music was more conventional in form, his way of telling a story in sound is simply phenomenal. He managed to take the Wagnerian style and omit the slower, duller passages in the latter’s operas where the orchestra simply acts as an accompaniment to the words being sung, which gave his music a constant flow. You can hear this in the second movement of this symphony, and it is to Järvi’s credit that he understood that slow movements still need forward momentum—something that many modern-day conductors forget even when playing Beethoven, Schubert or Brahms. I would also add that it is exactly this skill of Schmidt’s to create long and continually developing lines that is almost completely lacking in the music of many modern composers, who seem far too hung up on “effects.” Schmidt also avoided one device that always seemed to be a prescribed formula in symphonies and concerti of his time, and that is the sudden fast passage in the middle of the slow movement. In addition to the constant flow of ideas, his constantly “moving” orchestration, in which at least one section is playing something different from the rest of the orchestra, holds one’s attentions.

Such subtleties, however, are often missed by ears tuned to catch other things in the music. Many critics, including one who I will not name because I highly respect his ears and his opinions, described Schmidt’s symphonies as “good but not great,” yet it is exactly this layered sound and intermixture of details that make his symphonies great. There is really a lot going on in this music, but alas, much of it is “under the surface” where some ears fail to go. Each movement of this symphony is quite long, even the Scherzo (“Schnell und leicht”) which runs nearly eleven minutes, but it doesn’t feel long because your attention never wavers; and it is here, in the Scherzo, where Schmidt reverses the convention usually accorded second movements of symphonies by introducing a slow theme in the midst of the bustle rather than the other way around. Ironically, the theme of this slow section actually sounds a bit like Mahler.

In the fourth movement, Schmidt cleverly weaves in and out between the major and minor, so quickly, in fact, that if you’re not listening carefully you’ll miss it. Sometimes, these brief but telling key changes take place only in the subliminal lines of the music, such as in the basses but not in the top line. It’s almost like being in a cluttered Victorian living room where everything seems to be in place but the shifting lights coming in through the windows suddenly make things look briefly different, but you can’t say exactly how. The soft viola passage right in the middle is one such moment: don’t miss it! And then, note how he suddenly and almost nonchalantly shifts the meter from 4/4 to 6/8, then back to 4 when the tempo suddenly doubles…but the violas are still playing 6/8 beneath the 4/4!

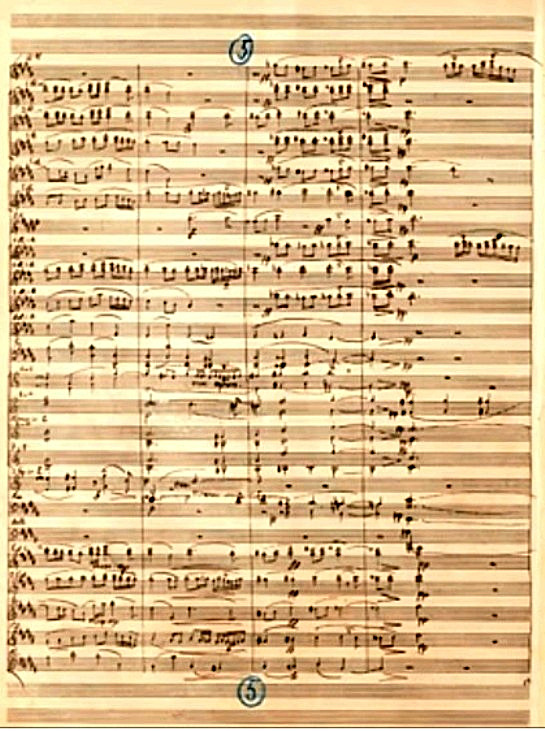

The second symphony was written from 1911 to 1913 and published the following year. Schmidt dedicated it to conductor Franz Schalk in hopes that he would perform it; he did, but much to Schmidt’s dismay, he discovered that Schalk didn’t have a true understanding of the piece. David Hurwitz, executive editor of Classics Today, described it as a real Gothic, “hairy knuckle” piece, but compared to Havergal Brian’s “Gothic” Symphony it’s not quite that. It is, however, much more muscular music, to be sure; here, Strauss seems to be his principal inspiration, but mixing in some of Salome with Ein Heldenleben, which it resembles in places; but once again, in the intricate low clarinet passages woven around the flutes with string tremolos tossed in for color, his orchestration is entirely his own. (I would think, in fact, that Strauss would have been a bit jealous of this symphony, but I’ve not been able to find any solid evidence.) At 7:25 in the first movement, Schmidt uncorks some absolutely incredible mushroom clouds of sound from the orchestra, something he never did again, followed by a strange-sounding solo for what sounds like a bass clarinet against the low strings before a luftpausen and yet another busy theme written with complex orchestration. Although this movement, in Järvi’s performance, runs 14:33, it doesn’t sound “long” because so much is going on.

Score page from the first movement of Schmidt’s Second Symphony

The second movement is more conventional thematically, using a fairly simple melodic line in 3/4, but again the music shifts and changes. Here, however, the music does sound episodic, even in such skilled hands as Järvi’s; I can just imagine how Schalk must have butchered this. It’s a surprisingly weak movement in Schmidt’s oeuvre, but only in terms of this episodic feeling; Orchestrally, it is again superb if here, perhaps, even more obviously Straussian. Schmidt makes up for this, however, in a superb third (and final) movement. Drawing on his experiences as an organist, he creates a very long, slow line for the opening which sounds very much like organ music transcribed for orchestra. One thing that I’ve not read about Schmidt’s music is that at times, like here, it resembles Max Reger’s, except that Reger’s orchestral textures were even thicker and didn’t usually have as many moving parts. In the development section, Schmidt doubles the tempo and turns it over to the violins, later brass and winds mixed in, as he doubles the tempo and suddenly envelops us in his by-now-expected web of sound, and he continues to shift and change the music as it goes on. It’s a very satisfying ending to this symphony and, once again, clearly simulates an organ.

Oddly enough, given his disappointment in Schalk’s performance of his Second Symphony, Schmidt let the same conductor give the premiere of the Third in December 1928. This is the symphony that Schmidt entered in the international contest run by the Columbia Graphophone Company for new symphonies in the spirit of the Unfinished” to honor the 100th anniversary of Schubert’s death. As everyone knows, it was Kurt Atterburg who won the top prize with what was then called his “million dollar symphony/” Schmidt did, however, win first prize in the “Austrian zone” of the International Prize. Although Schmidt’s symphony bears no resemblance to Schubert’s in form or structure, I would say that he definitely used a Schubert-like melody in the first movement; in any even, it is unlike his usual themes, being rather more melodic, and although it includes his usual subtle key shifts and moving bass lines, it is less complex and cluttered than usual for him. A very pastoral opening, then, and quite charming, which is different from the first two symphonies, although this first movement does eventually build up to a stunning climax.

It is in the second movement, however, that we notice a definite shift in Schmidt’s style, towards bitonality. This is noticeable from the very start of the movement although, as in the case of his key shifts in the earlier works, he sometimes goes back to a pure tonality before shifting once again towards a tonal mixture. In the second movement, the harmonic mixture is even subtler, pointing towards what he would do in this fourth symphony. The third-movement scherzo is also somewhat Schubert-like, or at least Schubert mixed with Schmidt, which you would have expected. But there’s a surprise: a little over three minutes into this movement, Schmidt stops the music dead before picking up the next theme—again, something that Schubert would have done but not normally Schmidt. Also unusual, for him, is the very chipper feeling he put into it. The fourth and last movement, surprisingly, opens with a “Lento” theme before suddenly moving into an “Allegro vivace,” again after a dead stop in the music. At 3:42 he suddenly brings the tympani in behind the orchestra for several bars, then drops it. All in all, a surprisingly playful symphony from Schmidt although it has his harmonic fingerprints all over it.

Then, at last, we arrive at his remarkable Fourth Symphony, written in 1933 and dedicated (finally) to another conductor, Oswald Kabasta, who premiered it with the Vienna Symphony (interesting…not the Philharmonic!). This was the culmination of his symphonic writing, a piece that is continuous from start to finish and clearly folded in several Mahlerian elements in addition to his subtle key changes, which are more frequent here and, in a way, become part of the overall structure, including the development sections. Hearing this work, one realizes what a shame it was that Schmidt never wrote a fifth symphony; everything about this piece is equally fascinating and emotionally moving. The music almost seems to pulsate as it continually morphs and develops in a continuous arch. By this time, too, Schmidt has become familiar with some of Schoenberg’s music and although he clearly did not go into 12-tone music, he also seemed to me to have had some ideas about how to incorporate even more frequent key shifts, which kept the harmony up in the air much of the time.

But I don’t think it was just Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire that he discovered by this time. This symphony, to my ears, also shows the influence of that same composer’s Verklärte Nacht—in addition to Strauss and Mahler. This may not have been a particularly forward-looking work, but it was a culmination of the German symphonic style which incorporated some then-20-yerar-older ideas into its basically Romantic structure. By and large, this symphony moves at an almost consistently moderate to slow pace, which allows the listener to absorb Schmidt’s masterful grasp of harmony in sort of “slow motion.” At the 4:40 mark in the slow(er) second movement, there is even a certain allusion to the funeral march from Beethoven’s Third Symphony, albeit updated in style and not quite as funereal in tempo. I can only hope that Oswald Kabasta did as good a job on this symphony as Järvi does here; he really nails this music in its strange combination of subtlety and power.

The Intermezzo from Schmidt’s opera Notre Dame is a nice piece, but I wish that Järvi had also included the Introduction and “Carnival Music” as Sinaisky did in the Naxos set. Even so, this is an outstanding set of performances that do full justice to Schmidt’s unusual but Romantic symphonies. This was clearly as far as the Romantic style could go without fully embracing the aesthetics of a Scriabin, Bartók, Stravinsky or Prokofiev as the symphonic form marched forward in both time and style. Kudos to everyone involved with this set, particularly the engineers who captured every note with clarity.

—© 2024 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Facebook (as Monique Musique)

Check out the books on my blog…they’re worth reading, trust me!