EÖTVÖS: Tri sestry (Three Sisters) / Ray Chenez, ctr-ten (Irina); David Dong Qyu Lee, ctr-ten (Mascha); Dmitry Egorov, ctr-ten (Olga); Mikołaj Trąbka, bar (Andrei); Eric Jurenas, ctr-ten (Natasha); Mark Milhofer, ten (Doctor); Krešimir Stražanac, bs-bar (Tusenbach); Barnaby Rea, bs (Soljony); Thomas Faulkner, bs-bar (Kulygin); Iain MacNeil, bar (Werschinin); Alfred Reiter, bs (Anfisa); Isaac Lee, ten (Rodé); Michael McCown, ten (Fedotik); Frankfurt Opera and Museum Orch.; Dennis Russell Davies, Nikolai Petersen, cond / Oehms Classics OC 986 (live: Frankfurt, September & October 2018)

EÖTVÖS: Tri sestry (Three Sisters) / Ray Chenez, ctr-ten (Irina); David Dong Qyu Lee, ctr-ten (Mascha); Dmitry Egorov, ctr-ten (Olga); Mikołaj Trąbka, bar (Andrei); Eric Jurenas, ctr-ten (Natasha); Mark Milhofer, ten (Doctor); Krešimir Stražanac, bs-bar (Tusenbach); Barnaby Rea, bs (Soljony); Thomas Faulkner, bs-bar (Kulygin); Iain MacNeil, bar (Werschinin); Alfred Reiter, bs (Anfisa); Isaac Lee, ten (Rodé); Michael McCown, ten (Fedotik); Frankfurt Opera and Museum Orch.; Dennis Russell Davies, Nikolai Petersen, cond / Oehms Classics OC 986 (live: Frankfurt, September & October 2018)

Anton Chekhov’s play Tri sestry is complicated enough to start with—typically Russian in its plethora of conflicting emotions, illicit love affairs (lots of them), drinking and gambling—but Hungarian composer Peter Eötvös made it doubly so by setting it to edgy, complex modern music absolutely guaranteed to turn off the average opera-lover who wants his Tunes and wants them Now. Absolutely nothing in this music makes the least concession to popular tastes and, worse yet, he has committed the cardinal sin of casting the three sisters, as well as their brother’s great love Natasha, as countertenors instead of female singers.

I myself was worried about the latter since I generally can’t stand countertenors, but not only are all three of them excellent singers, musicians and actors, but in many places I couldn’t even tell that they were countertenors, so interesting and pleasant were their voices (particularly David DQ Lee). There is little or no countertenor “hoot” in their singing, and all in all I was very pleased with the results.

As for the music, well, you’re on your own there. Eötvös evidently views the Chekhov play the same way I do, as a confused, tangled mess of personal relationships and inner power struggles, and thus wrote somewhat confused, tangled music that is constantly edgy. I mean, really now, do you really want an opera based on Three Sisters to be full of Romantic music, lovely tunes etc. when the plot is such a simmering stew of envy and selfishness? I mean, after all, these “three sisters” are about as pleasant as Rashida Tlaib, Elisabeth Warren and Hillary Clinton at a Young Republicans rally. They pretty much hate anyone and anything that doesn’t agree with them and, at the very least on a subliminal level, would like to eradicate those who don’t.

The one downside I had to reviewing this recording was the lack of a libretto. This was a real handicap in a plot as complex and knotty as this one, and I had a difficult time following the sequence of events, particularly since the composer and Claus H. Henneberg simplified and rewrote several scenes for the libretto. Yet the booklet notes give some indication of how they treated this plot, which stretches over three full years and plenty of hormonal mood swings for our intrepid sisters:

The libretto of the opera Tri sestry, written by Claus Henneberg and Peter Eötvös, destroys Chekhov’s construction of time. It has lost its straightforwardness, seems to be more circular than linear and hardly allows meaningful goals to be derived. Nevertheless, the most important plot elements of Chekhov’s play are certainly presented in the opera, and some of them even several times. However, what in the opera initially looks only like a repetition of the story with a focus on the figures of Irina, Andrei and Masha, involves a complex de-construction of the order of time. Even a rough survey of the use of the textual material of Chekhov’s play in Eötvös’ opera (see box) shows that the opera not only takes up the plot of the play sometimes in non-chronological order and repetitively, but also fragments it, compresses it and dynamizes it. The very prologue to the opera constitutes a com-pressed form of the final words by the three sisters in the play, so that the real ending now symbolically becomes the beginning in the opera.

The plot of Sequence I does not quite follow the chronology laid down by Chekhov, but in the opera, too, Irina’s story can be understood in a possible time sequence: she wishes for a life with work, is courted by two men, declares herself willing to marry and finally loses her betrothed to the duel between the two men. However, this reconstruction of Irina’s story refers to the text after No. 6 until the end of the sequence. By contrast, the montage of the textual material in Nos. 2 to 5 of the opera by no means permits a logical construction of the plot. For the text presented here seems to be without any order because the information conveyed cannot yet be conclusively understood in an overall context. The text plays for time by delaying the beginning of the comprehensible story, which ultimately serves to stretch time.

Sequence II, devoted to Andrei, fragments the story of the figure depicted by Chekhov. Andrei’s path from the dreamer to the resigned and cuckolded husband and father, who, under the dominance of his wife, has become reconciled to the pettiness of life in rural Russia, can no longer be followed in the time scheme of the opera. The important stages in Andrei’s development are not discernible in chronological order, so his character seems static – timeless. The ensemble in No. 18 can be interpreted as a symbol of this form of presentation, aiming at simultaneity and the fragmentation of context. In conventional opera literature, the employment of ensembles frequently leads to the effect that the narrated time of the plot stands still for the length of the passage. Let us only think of the corresponding passages from the famous quintets or sextets by Rossini or Donizetti, in which the usually conflicting emotions of the protagonists concerning a specific moment of the plot are expressed simultaneously and hence in the stasis of narrated time. The just under two-minute ensemble in No. 18 in Eötvös’ opera, in which Andrei, Olga and Masha do not take part, follows this tradition of synchronization and time standstill. The material from Chekhov used here consists of small elements of text from Acts II and III, torn out of context and assembled as a collage.

So there you have it. I hope it makes some sense to you but for me, who has never seen or read the Chekhov play, it seemed just as confusing as reading a synopsis of the original. My reaction when confronted with a plot as convoluted as this one is always, To what end? Translation: I really don’t care about these characters. To me, they’re just selfish pigs who think their “great intelligence” gives them the right to tell other people how to live their lives, boss each other around, and cheat on their husbands as if they didn’t exist. Perhaps this was Chekhov’s way of showing the undercurrent of women’s rebellion in a male-dominated society (in fact, I’m pretty sure it was), but to me the solution seems just as bad as the cause of their frustration. The real solution, which many contemporary British, French and American women of the time used, was to stay single, have affairs when and with whom you really want, but otherwise control your own life and stay out of the lives of others.

With that being said, Eötvös’ music really is interesting and creative. For all its atonal bent it rarely sits still but keeps evolving as the opera proceeds. I was also impressed by the unusual timbral blends he achieved in the music, some quite subtle and some not (the beginning of Sequence 2 sounds like an explosion in a boiler factory) but all of them unique and interesting.

The question is whether or not such an edgy, extroverted score really conveys what Chekhov had in mind. When the play premiered in January 1901, Chekhov felt that Stanislavsky’s “exuberant” direction had masked the subtleties of the work and only one actress showed her character evolving in the manner Chekhov intended. By completely rearranging the plot and infusing it with such edgy music, Eötvös appears to be following in the footsteps of Stanislavsky rather than Chekhov.

This is not an inconsequential difference. One cannot play, for instance, Hamlet the way one plays Otello. The former is a conflicted man fighting several demons while trying to avenge his father’s death and maintain his sanity; the latter is a fairly simple, heroic character driven by emotion who Iago plays like a fiddle. Iago could never have swayed a Hamlet: the latter’s more complex and subtle way of thinking would have demanded more proof before he acted.

But if one accepts Eötvös’ Tri sestry as an entirely different work from Chekhov’s, which in his rearranging of scenes and elimination of subtlety it most certainly is, the opera works. Eötvös has made this an edgy, psychological drama on a par with Lulu or Peter Bengtson’s The Maids. Does he have a right to do this? Certainly, as long as he makes it clear that the opera is merely based on Chekhov and not a faithful transcription of his play. And between you and me, I feel that the story works better when you let the characters open up their emotions this way rather than smothering them until they’re suffocating under the weight of their own self-importance and desire to control the lives of others.

Part of this also has a lot to do with the Women’s Liberation movement which started in the late 1960s. Women in 1901, in every country, were still under the yoke of men; women in 1998 are not in any significant way except in Muslim countries. Consider women’s voting rights. In the United Kingdom, women had no right to vote anywhere until two laws were passed, the first in 1918 and the second a decade later. In the United States, certain states and municipalities allowed women to vote as early as 1870, but it was not widespread until a national law was passed in 1920. We’re so far beyond that stage now that most women, including myself, can’t even think of it as having been a reality at one time.

This is not a digression. This view is central to the theme of Tri sestry. Even if Eötvös retained many of the situations in the original, we need to view them through the prism of our own experience. To watch a production of the play as Chekhov originally conceived it would seem, pardon the pun, inconceivable to we women today. It also makes sense that this production was updated to our time. Eötvös was viewing the problems of Chekhov’s three sisters in 1901 through the lens of three women, placed in the same situations, 97 years later.

So there you have it. I like it for what it is, and as a woman I respond to Eötvös’ view a lot better than I respond to Chekhov’s. Had he titled the opera Tri sestry 1998, I don’t think there would be any friction or confusion with the play.

Quite aside from the excellent and almost unbelievable singing of our three countertenors, the entire production is strongly cast and brilliantly conducted. Both conductor Dennis Russell Davies and his singers throw themselves into the work, bringing out great detail in addition to great excitement. Only bass-baritone Thomas Faulkner, as Kulygin, has a wobbly, unfocused voice.

Thus I recommend this work and this performance. It’s engaging, interesting, and wonderfully edgy in a good way.

—© 2019 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter (@Artmusiclounge) or Facebook (as Monique Musique)

Return to homepage OR

Read The Penguin’s Girlfriend’s Guide to Classical Music

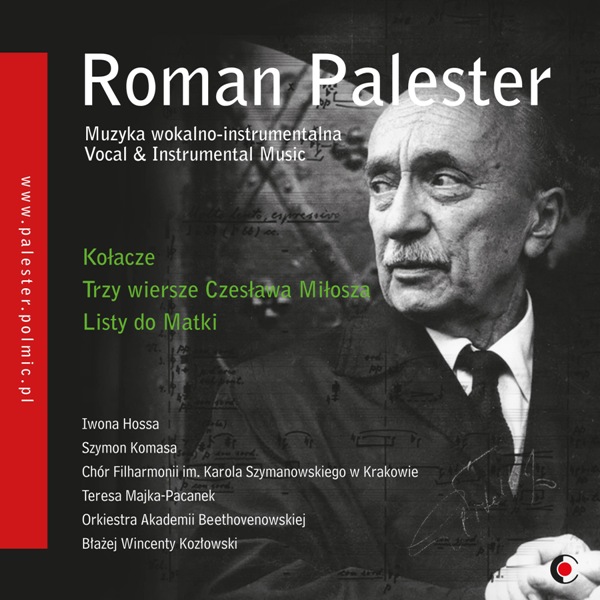

PALESTER: The Wedding Cake.1 3 Poems by Czesław Miłosz.2 Letters to Mother3 / 2Iwona Hossa, sop; 3Szymon Komosa, bar; 1Women’s Choir of the Karol Szymanowski Philharmonic, Krakow; Beethoven Academy Orch.; Błaźej Wincenty Kozlowski, cond / RecArt 0025

PALESTER: The Wedding Cake.1 3 Poems by Czesław Miłosz.2 Letters to Mother3 / 2Iwona Hossa, sop; 3Szymon Komosa, bar; 1Women’s Choir of the Karol Szymanowski Philharmonic, Krakow; Beethoven Academy Orch.; Błaźej Wincenty Kozlowski, cond / RecArt 0025