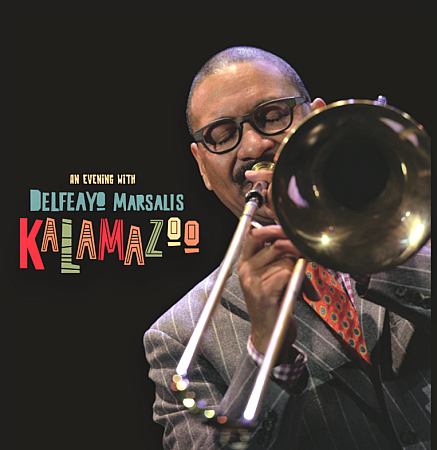

KALAMAZOO (AN EVENING WITH DELFEAYO MARSALIS) / ROPPOLO-POLLACK-STITZEL: Tin Roof Blues. PRÉVERT-KOSMA-MERCER: Autumn Leaves. RODGERS-HART: My Funny Valentine. RAPOSO-HART-STONE: Sesame Street Theme. LOESSER: If I Were a Bell. D. MARSALIS: The Secret Love Affair. ELLINGTON-MILLS: It Don’t Mean a Thing. D. MARSALIS-DIAZ: Kalamazoo.* ALTER-DeLANGE: Do You Know What it Means (to Miss New Orleans?) / Delfeayo Marsalis, tb; Ellis Marsalis Jr., pn; Reginald Veal, bs; Ralph Peterson, dm; *Christian O’Neill Diaz, voc / Troubador Jass Records 713869572501

Delfeayo Marsalis, like his sax-playing brother Branford, once played and recorded modern jazz, but now it appears that his band—now a quartet including his father Ellis on piano—is more attuned to playing mostly retro tunes from the 1920s and ‘30s like his trumpet-playing brother Wynton. Whatever the motivation, however, the resultant music is relaxed, much of it falling into a very nice groove, what jazz musicians like to call a “coochy” feeling. This is Delfeayo’s first live album, recorded on tour while promoting their The Last Southern Gentleman CD.

As a trombonist and improviser, Delfeayo falls somewhere in the Lawrence Brown-Dicky Wells style. He has impeccable technical control of his instrument, and thus is able to play anything he chooses to without fear that his chops will fail him. In the opener, Tin Roof Blues, he even plays a string of rapid lipped notes à la J.J. Johnson, not an easy feat (I seriously doubt that many classical trombonists could do it) while maintaining that nice, burry tone that only jazz trombonists seem able to produce. His brother’s piano solo is pleasant but, to my ears, not on the same high level of creativity, but bassist Reginald Veal makes up for this with a sensational bass solo, using the slow tempo as a means of spacing out his notes with great taste.

Despite the fact that Autumn Leaves is generally played at a medium-slow tempo, Marsalis tears into it at a surprisingly fast clip, and his opening solo contains elements of swing, blues, and even bop trombone. More importantly, his solo is a cohesive piece of music and “tells a story,” as jazz critics once said a half-century ago. Ellis is rather more animated here on the keyboard, playing in a nice groove and finding some nice licks, though he does toss in a quote from Yes Sir, That’s My Baby. After a nice drum solo by Ralph Peterson, Marsalis returns, but although he plays well here it’s not quite as stunning as that opening solo.

Although Delfeayo does a nice job on My Funny Valentine, somehow the performance falls a bit flat. Sometimes you just don’t mess with tunes that legendary jazz musicians made their own, although to be honest I’m not sure that either Ellis or Delfeayo thought that much about Chet Baker when performing this. It just happened to not come out great. On the other hand, their creative reworking of the Sesame Street Theme as a blues is both fun and very creative. I don’t know why, but while listening to it my mind flashed on the late Vince Guaraldi…it’s exactly the kind of thing he would have done, and had a ball with. Ellis plays a typically sparse solo, with Peterson contributing some nice backbeats on the snare and cymbals. Delfeayo gives us some growls in his solo, apparently using both a straight mute and a plunger, which stays within a fairly narrow emotional and note range but makes a nice impression.

If I Were a Bell belongs primarily to Ellis on piano, playing very nice swing style, followed by bassist Veal doing an incredible Slam Stewart imitation, singing along with his bowed bass. The Secret Love Affair is an original by Delfeayo with a Latin beat, played very nicely. Ellis throws in a quote from Summertime at the beginning of his laid-back solo, but it is Delfeayo’s second solo that is the real gem in this performance.

Duke Ellington’s It Don’t Mean a Thing, the first “cover” of which was made by the Boswell Sisters and Bunny Berigan in 1932, receives a laid-back, medium-tempo performance from the band. Ellis seems intent on tossing in quotes from other tunes, including Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho, Yes Sir That’s My Baby, Blue Skies and Swing on a Star, but the audience, clapping in time to the rhythm, seems to be enjoying it immensely. By contrast with his father, Delfeayo is wholly original in his solo, finding new avenues to explore in Duke’s classic tune. Peterson’s drum solo is a bit flashy but has a nice dance-like flow and logic about it (put me in mind a bit of Baby Laurence).

The next track is an introduction to Kalamazoo, a spontaneously improvised blues tune that has nothing whatever to do with the Mack Gordon-Harry Warren classic from 1942. Guest vocalist Christian O’Neill Diaz has the scat solo. It’s a nice piece, if not a particularly great one.

The closer is Louis Armstrong’s 1946 hit, Do You Know What it Means to Miss New Orleans?, played as an almost wistful, slow ballad. Delfeayo’s tone is at its warmest here, very close to the way Lawrence Brown sounded, and after the theme statement his solo is wonderfully original, full of little surprises. In his second solo, Delfeayo again pulls out the plunger mute, this time giving us a bit of the ol’ wa-wa style of the 1920s and ‘30s.

All in all, a warm, relaxed evening of music, played with quite a bit of affection by the quartet.

—© 2017 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter! @Artmusiclounge

Read my book, From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed guide to the intersection of classical music and jazz