Pauline Viardot in old age

After having discovered the marvelous German songs of Pauline Viardot-Garcia in the album by Miriam Alexandra, I decided to explore further some of the various other recordings of her music available. In addition, I tried as much as possible to zero in on recordings by singers whose voices came close to the verbal descriptions of Viardot’s own voice in order to get, as the academics would crow from the balcony, as close as possible to the way the artist herself actually sang her own material.

This, of course, is not easy, and not just because Viardot never recorded. It’s difficult because she had one of those rare voices that was extraordinarily large and extraordinarily flexible: try to imagine a combination of Jon Vickers and Juan Diego Florez (or, on the distaff side, Birgit Nilsson and Kathleen Battle). Such voices don’t normally exist in nature, but she had that kind of voice. Heinrich Heine, the German poet, described it thus:

She is not merely a nightingale who delights in trilling and sobbing her songs of spring. Nor is she the rose, being ugly, but in a way that is noble…She reminds us more of the terrible magnificence of a jungle rather than the civilized beauty and tame grace of the European world.

One of her greatest admirers, composer Camille Saint-Saëns, was more exact in his description:

Her voice was enormously powerful, had a prodigious range and was equal to every technical difficulty but, marvelous as it was, it did not please everybody. It was not a velvet or crystalline voice, but rather rough, compared by someone to the taste of a bitter orange, and made for tragedy or myth, superhuman rather than human; light music, Spanish songs and the Chopin mazurkas she transcribed for the voice, were transfigured by it and became the triflings of a giant; to the accents of tragedy, to the severities of oratorio, she gave an incomparable grandeur.

Thus we have a description of Viardot as woman singer: “ugly beauty,” transformed in the crucible of her soul into something that deeply moved the most sensitive and musical of listeners with something indescribable. By these accounts, the very pretty voice of Miriam Alexandra is not an approximation of how Viardot herself sang, fine though her performances were.

To find a singer, or singers, whose voices come close to Viardot’s we have to pick and choose. Soprano Soile Iskoski, who has also recorded her songs, is a marvelous interpreter but has a defective high soprano voice—not the right fit. Soprano and mezzo Cecilia Bartoli, who has recorded her Hai Luli!, Havanaise and Les Filles de Cadix, comes closer.

But the two who impressed me the most were Bulgarian Ina Kancheva, in her stupendous recital on Toccata Classics 0303, and Russian Julia Sukmanova on Fontenay Classics FC1006. Both have rich, deep lower ranges—remember that Viardsot-Garcia was a mezzo-soprano and not a soprano—and in addition Kancheva has the remarkable flexibility demanded to sing all those trills, mordents and appoggiatura. And this brings us to a more important and germane discussion, which was Viardot’s composing style.

As someone who was originally set to be a concert pianist, Viardot knew her instrument intimately, and with her quick ear and studies in harmony and composition she was able to absorb musical styles like a sponge. In the liner notes for the Kancheva recital there is a remarkable anecdote:

One day her husband was visited by a friend who admired Mozart above all composers, and Pauline announced that she wanted to sing for them a magnificent aria by Mozart that she had recently discovered. She sang a long aria, with recitatives, arioso and a final allegro, which the two men praised highly without knowing that she wad written it herself specifically for the occasion. Saint-Saëns remembered that he, too, had heard the aria, and attested to the fact that “even the sharpest critic might have been taken in by it,” He continued:

“But we shouldn’t imagine from this that her compositions were pastiches; on the contrary, they had a highly original flavor. Why is it that those that were published are so little known? One is led to believe that this admirable artist had a horror of publicity. For over half of her life she taught pupils, and the world was unaware of it.”

Further on in the notes, Saint-Saëns goes further on her composing style:

I do not know how she learnt the secrets of composition; apart from handling the orchestra, she knew them all and the numerous lieder she wrote on French, German and Spanish texts testify to an impeccable technique. In contrast to most composers for whom nothing is more urgent than publicity for their products, she concealed hers as though they were a fault; it was extremely hard to persuade her to have them performed; the least of them, though, would have done her honor. She announced as a popular Spanish song one with a savage tone and relentless rhythms, which Rubinstein was infatuated with; it took me several years to get her to admit that she was the composer.

Here’s a small example (one of the few I could find online) of her writing, the last page of her song Bonjour, mon cœur:

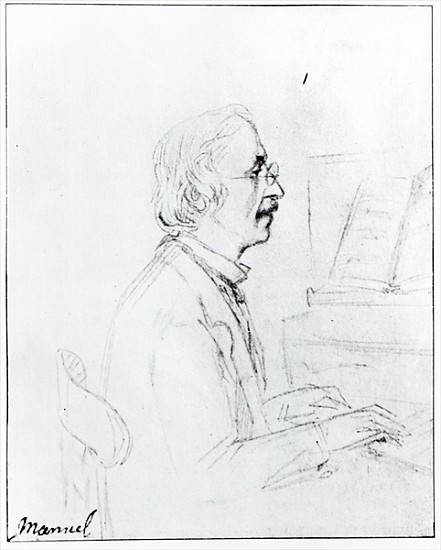

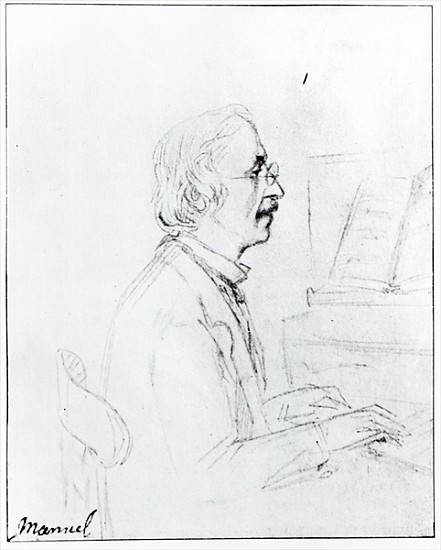

A highly intelligent and complex woman, Viardot-Garcia was hailed by all who met her. Schumann, Brahms, Liszt and Wagner were among her friends and admirers. Clara Schumann once asserted that she was the most intelligent woman she had ever met in her life. Viardot was also a surprisingly fine sketch artist and caricaturist; here is her drawing of her father, Manuel Garcia Sr.:

Because of her high intelligence, linguistic skill (she spoke French, German, English, Italian and Russian fluently, and sang like a native in all five) and remarkable musical and poetic intuition, Viardot attracted the most sensitive and intelligent men in all of Europe despite her homely appearance. The Russian poet Ivan Turgenev saw her perform Rosina in The Barber of Seville at St. Petersburg in 1843 and remained hopelessly in love with her for the next 40 years. She set many of his poems to music and in fact he eventually lived into the house next door to her until he died in 1883. Viardot also set more poems by Alexander Pushkin to music than any Russian composer, and was the first to set the famous Les filles de Cadiz to music, years before Délibes tried his hand.

Listening to her Russian songs as sung by Kancheva (you can find sound clips of some of the songs on YouTube under her name), after having heard the German songs sung by Alexandra, one is startled by the completely different musical style. One would never guess that they were written by the same composer, so entirely different is their treatment of melody, harmony and rhythm. The Russian songs almost sound like something Glinka or Mussorgsky would have written, whereas, as I said in my earlier review, the German songs would do honor to Schubert or even to Schumann without really copying anything they had composed.

Listening to her Russian songs as sung by Kancheva (you can find sound clips of some of the songs on YouTube under her name), after having heard the German songs sung by Alexandra, one is startled by the completely different musical style. One would never guess that they were written by the same composer, so entirely different is their treatment of melody, harmony and rhythm. The Russian songs almost sound like something Glinka or Mussorgsky would have written, whereas, as I said in my earlier review, the German songs would do honor to Schubert or even to Schumann without really copying anything they had composed.

And then we reach the Chopin Mazurkas. She set 12 of them to lyrics, admittedly rather poor lyrics, in two sets of six each. The last mazurka in each set is a vocal duet. Who did she herself sing them with? We may never know. She actually performed them with Chopin, another friend of hers, at the piano on occasion. These are the most often recorded of her songs, but Kancheva sings them as I imagine Viardot herself did, with the voice of a lion. The performances are entirely remarkable, as are the songs themselves. To hear so large and powerful a voice turning mordents and trills at the speed of light is simply astonishing; it is probably the closest we will get in our lifetimes to hearing Viardot herself.

As yet another facet in her style, we then turn to the Italian and French songs. Here we must rely on another very pretty voiced soprano, in this case the remarkable Isabel Bayrakdarian, who sang at the Metropolitan Opera very briefly in the early 2000s, on Analekta AN29903. It would be easy to dismiss her performances as not being like Viardot’s own, but Bayrakdarian caresses the line with such evident love and extraordinary brilliance of tone that we are immediately captivated. But to complete this series of French and Italian songs, we need to turn to mezzo-soprano Marina Comparato on Brilliant Classics BC94615. Here, she presents us with a piece I didn’t even know existed, a vocal version of the Haydn String Quartet “Serenade,” the one that was for decades ascribed to Roman Hofstetter but is now again accepted as authentic Haydn (mostly because none of Hofstetter’s other quartets are nearly as distinguished). Following this are the

As yet another facet in her style, we then turn to the Italian and French songs. Here we must rely on another very pretty voiced soprano, in this case the remarkable Isabel Bayrakdarian, who sang at the Metropolitan Opera very briefly in the early 2000s, on Analekta AN29903. It would be easy to dismiss her performances as not being like Viardot’s own, but Bayrakdarian caresses the line with such evident love and extraordinary brilliance of tone that we are immediately captivated. But to complete this series of French and Italian songs, we need to turn to mezzo-soprano Marina Comparato on Brilliant Classics BC94615. Here, she presents us with a piece I didn’t even know existed, a vocal version of the Haydn String Quartet “Serenade,” the one that was for decades ascribed to Roman Hofstetter but is now again accepted as authentic Haydn (mostly because none of Hofstetter’s other quartets are nearly as distinguished). Following this are the  10 Mélodies, “Album du Chant.” Comparato has a somewhat prominent vibrato, which was not something Viardot-Garcia possessed, and the recorded sound is also somewhat overly reverberant which exacerbates the vibrato, but they are all we have of these remarkable songs. In neither the downloads of the Bayrakdarian disc or in the hard copy of the Comparato CD are there any texts or translations of these songs, but do not despair. I highly recommend Emily Ezust’s stupendous “LiederNet Archive” at http://www.lieder.net/lieder/index.html, where she has at least the original texts of most of these songs and the English translations of many. But please do not overlook her request for donations to help keep the site up. This is a labor of love for her and she has spent hundreds of thousands of hours providing this invaluable information to art song lovers worldwide since the mid-1990s.

10 Mélodies, “Album du Chant.” Comparato has a somewhat prominent vibrato, which was not something Viardot-Garcia possessed, and the recorded sound is also somewhat overly reverberant which exacerbates the vibrato, but they are all we have of these remarkable songs. In neither the downloads of the Bayrakdarian disc or in the hard copy of the Comparato CD are there any texts or translations of these songs, but do not despair. I highly recommend Emily Ezust’s stupendous “LiederNet Archive” at http://www.lieder.net/lieder/index.html, where she has at least the original texts of most of these songs and the English translations of many. But please do not overlook her request for donations to help keep the site up. This is a labor of love for her and she has spent hundreds of thousands of hours providing this invaluable information to art song lovers worldwide since the mid-1990s.

Following Bayrakdarian and Comparato, we then turn to another dark-voiced Slavic singer, Julia Sukmanova on Fontenay Classics FC1006. This album has texts in German only, but 13 of the songs here are duplicated in the Miriam Alexandra CD. Nevertheless, I strongly urge you to acquire these performances because of the richer, deeper quality of Sukmanova’s voice and her emotionally powerful delivery. She literally transforms this music, giving you more meat and less perfume, if you know what I mean. Moreover, her pianist is her sister, Elena, and she is absolutely terrific, a fit partner for her sister’s emotional delivery.

Following Bayrakdarian and Comparato, we then turn to another dark-voiced Slavic singer, Julia Sukmanova on Fontenay Classics FC1006. This album has texts in German only, but 13 of the songs here are duplicated in the Miriam Alexandra CD. Nevertheless, I strongly urge you to acquire these performances because of the richer, deeper quality of Sukmanova’s voice and her emotionally powerful delivery. She literally transforms this music, giving you more meat and less perfume, if you know what I mean. Moreover, her pianist is her sister, Elena, and she is absolutely terrific, a fit partner for her sister’s emotional delivery.

Viardot also wrote a Violin Sonatina in A minor, but this is disappointing. She really didn’t know how to write for the violin and so fell back on her song experience. It’s tuneful but not particularly interesting. Better are the 6 Morceaux for violin and piano, particularly Nos. 2-4 and 6. There are several recordings available of these, but the ones I enjoyed the most were the performances by violinist Laura Kobiyashi and pianist Susan Keith Gray on Albany TROY1081. Viardot also wrote a charming “chamber opera with piano” for children, Cendrillon. I found a few different performances of it on YouTube, but the best of them was the one given by singers of the Westminster Choir College. It’s also easier to follow because the copious dialogue is spoken in English. My thanks to David Hansel for bringing this work to my attention! It’s not a great opera, but it is remarkably charming, witty and very well written. Typical of Viardot, she wrote it in the mid-1880s but it wasn’t premiered until 1904, when she was 83 years old.

I absolutely guarantee you that you will not be disappointed in exploring the music of this remarkable woman. As Saint-Saëns said, even the “weakest” song is well constructed and lovely, while the majority of them are much more than that. Bon appetit!

—© 2017 Lynn René Bayley

Listening to her Russian songs as sung by Kancheva (you can find sound clips of some of the songs on YouTube under her name), after having heard the German songs sung by Alexandra, one is startled by the completely different musical style. One would never guess that they were written by the same composer, so entirely different is their treatment of melody, harmony and rhythm. The Russian songs almost sound like something Glinka or Mussorgsky would have written, whereas, as I said in my earlier review, the German songs would do honor to Schubert or even to Schumann without really copying anything they had composed.

Listening to her Russian songs as sung by Kancheva (you can find sound clips of some of the songs on YouTube under her name), after having heard the German songs sung by Alexandra, one is startled by the completely different musical style. One would never guess that they were written by the same composer, so entirely different is their treatment of melody, harmony and rhythm. The Russian songs almost sound like something Glinka or Mussorgsky would have written, whereas, as I said in my earlier review, the German songs would do honor to Schubert or even to Schumann without really copying anything they had composed. As yet another facet in her style, we then turn to the Italian and French songs. Here we must rely on another very pretty voiced soprano, in this case the remarkable Isabel Bayrakdarian, who sang at the Metropolitan Opera very briefly in the early 2000s, on Analekta AN29903. It would be easy to dismiss her performances as not being like Viardot’s own, but Bayrakdarian caresses the line with such evident love and extraordinary brilliance of tone that we are immediately captivated. But to complete this series of French and Italian songs, we need to turn to mezzo-soprano Marina Comparato on Brilliant Classics BC94615. Here, she presents us with a piece I didn’t even know existed, a vocal version of the Haydn String Quartet “Serenade,” the one that was for decades ascribed to Roman Hofstetter but is now again accepted as authentic Haydn (mostly because none of Hofstetter’s other quartets are nearly as distinguished). Following this are the

As yet another facet in her style, we then turn to the Italian and French songs. Here we must rely on another very pretty voiced soprano, in this case the remarkable Isabel Bayrakdarian, who sang at the Metropolitan Opera very briefly in the early 2000s, on Analekta AN29903. It would be easy to dismiss her performances as not being like Viardot’s own, but Bayrakdarian caresses the line with such evident love and extraordinary brilliance of tone that we are immediately captivated. But to complete this series of French and Italian songs, we need to turn to mezzo-soprano Marina Comparato on Brilliant Classics BC94615. Here, she presents us with a piece I didn’t even know existed, a vocal version of the Haydn String Quartet “Serenade,” the one that was for decades ascribed to Roman Hofstetter but is now again accepted as authentic Haydn (mostly because none of Hofstetter’s other quartets are nearly as distinguished). Following this are the  10 Mélodies, “Album du Chant.” Comparato has a somewhat prominent vibrato, which was not something Viardot-Garcia possessed, and the recorded sound is also somewhat overly reverberant which exacerbates the vibrato, but they are all we have of these remarkable songs. In neither the downloads of the Bayrakdarian disc or in the hard copy of the Comparato CD are there any texts or translations of these songs, but do not despair. I highly recommend Emily Ezust’s stupendous “LiederNet Archive” at

10 Mélodies, “Album du Chant.” Comparato has a somewhat prominent vibrato, which was not something Viardot-Garcia possessed, and the recorded sound is also somewhat overly reverberant which exacerbates the vibrato, but they are all we have of these remarkable songs. In neither the downloads of the Bayrakdarian disc or in the hard copy of the Comparato CD are there any texts or translations of these songs, but do not despair. I highly recommend Emily Ezust’s stupendous “LiederNet Archive” at  Following Bayrakdarian and Comparato, we then turn to another dark-voiced Slavic singer, Julia Sukmanova on Fontenay Classics FC1006. This album has texts in German only, but 13 of the songs here are duplicated in the Miriam Alexandra CD. Nevertheless, I strongly urge you to acquire these performances because of the richer, deeper quality of Sukmanova’s voice and her emotionally powerful delivery. She literally transforms this music, giving you more meat and less perfume, if you know what I mean. Moreover, her pianist is her sister, Elena, and she is absolutely terrific, a fit partner for her sister’s emotional delivery.

Following Bayrakdarian and Comparato, we then turn to another dark-voiced Slavic singer, Julia Sukmanova on Fontenay Classics FC1006. This album has texts in German only, but 13 of the songs here are duplicated in the Miriam Alexandra CD. Nevertheless, I strongly urge you to acquire these performances because of the richer, deeper quality of Sukmanova’s voice and her emotionally powerful delivery. She literally transforms this music, giving you more meat and less perfume, if you know what I mean. Moreover, her pianist is her sister, Elena, and she is absolutely terrific, a fit partner for her sister’s emotional delivery.

In certain passages, such as the opening of the Eighth Sonata, Trull creates real magic in the way she phrases and articulates the music. In the second movement of this work, she caresses the line and makes it sing in a way I’ve never quite heard before, almost making it sound like a tune from a Viennese operetta. In the second movement of the Ninth Sonata, she finds much more in the shifting rhythms of the middle section than others. Watching her old performances on YouTube, I noticed a difference in posture between her playing and that of a real idol of mine, Annie Fischer. Petite as she was, Fischer sat bolt upright at the keyboard; all of her power was generated by her muscular arms and shoulders. Trull, who appears to be a small-boned woman, hunches over the keyboard so that you rarely see her face. She attacks here instrument as if she has been sent by a wrecking crew to demolish the keyboard. There may be some shoulder motion here, but a close-up photo reveals that she had small, sloping shoulders. I think all her power is generated by her forearms and full-body energy. It’s quite astonishing to watch!

In certain passages, such as the opening of the Eighth Sonata, Trull creates real magic in the way she phrases and articulates the music. In the second movement of this work, she caresses the line and makes it sing in a way I’ve never quite heard before, almost making it sound like a tune from a Viennese operetta. In the second movement of the Ninth Sonata, she finds much more in the shifting rhythms of the middle section than others. Watching her old performances on YouTube, I noticed a difference in posture between her playing and that of a real idol of mine, Annie Fischer. Petite as she was, Fischer sat bolt upright at the keyboard; all of her power was generated by her muscular arms and shoulders. Trull, who appears to be a small-boned woman, hunches over the keyboard so that you rarely see her face. She attacks here instrument as if she has been sent by a wrecking crew to demolish the keyboard. There may be some shoulder motion here, but a close-up photo reveals that she had small, sloping shoulders. I think all her power is generated by her forearms and full-body energy. It’s quite astonishing to watch!