As soon as I heard the CD reviewed below, I knew that I wanted to interview the artists, Tara Helen O’Connor and Margaret (a.k.a. Peggy) Kampmeier, because not only was the music interesting and challenging but their playing was so exciting. It isn’t often that I go out of my way to contact an artist, but I did so in this case, and I’m glad I did, because they are just as lively and interesting as the music they play.

Between performing and teaching, O’Connor is one of the busiest musicians on the scene today. She performs at the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival, Chamber Music Northwest and the Spoleto Chamber Music Festival of Charleston, South Carolina; she is a member of the New Millennium Ensemble, Windscape, Andalucian Dogs and the Bach Aria Group; and she teaches at Purchase College at the State University of New York. Her musical partner on this disc, pianist Peggy Kampmeier, is Artistic Director and Chair of the Contemporary Performance Program at the Mannes College of Music and Studio Instructor at Princeton University’s Department of Music. She performs regularly with the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Sherman Chamber Ensemble and (believe it or not!) Peter Schickele’s P.D.Q. Bach concerts as well as numerous new music ensembles, so as you can see, this is a busy and versatile duo.

I caught up with them via e-mail to ask a few pertinent questions about this CD project and their approach to music in general.

Art Music Lounge: Tara, let’s start with you, but Margaret can jump in any time she wants. My initial reaction to your CD was twofold: one, I not only liked the music I heard but found it interesting and well constructed, something that not all modern music is; and two, I was absolutely blown away by the intensity of your playing. Clearly, for you music is not just a job but a personal mission. Would that be a fair statement?

Tara Helen O’Connor: Absolutely. I approach all music in the same way. I search for the emotional, physical and spiritual motivation that lays behind the notes. This could manifest as tone color, articulation, inflection or any of countless nuances of sound and rhythm. The main thing is to be authentic to the aesthetic of the composer.

AML: Peggy, I’m guessing that it’s much the same for you as well. I reviewed one of your previous CDs, a recital of songs by Kaikhosru Sorabji sung by Elizabeth Farnum on Centaur, and I was struck as much by your playing as by Farnum’s singing. I suppose that you specialize in contemporary music for a reason, right?

Peggy Kampmeier: That’s a great question. It’s so important to me to be involved with the music of our time. As a performer, that means giving voice to new and unfamiliar works, both in performance and in recording. Interpreting contemporary music has much to do with learning the languages of individual composers – “cracking the code,” so to speak, and this is forever fascinating to me. By the way, when I first moved to New York, I became known as a new music specialist, but I’ve always played all kinds of music.

AML: Tara, one of the things that impressed me about your CD was the no-holds-barred approach you take to flute playing. This is not to say that you don’t have perfect control of your instrument, rather that you take it to the limit at all times. I’m wondering if you take the same gung-ho approach to the music of Bach, Mozart, etc.?

THO: Absolutely. Again, I take the same approach to all music. I like to know the conventions of performance practice in all periods coupled with my instinct and my taste. I don’t try to play on the edge for its own sake, but rather I follow the music where it takes me. It’s an informed process that I hope brings me as close as I can be to the composers wishes. After all, we as performers are the vehicles of expression for the music of the past and our contemporaries.

AML: This question is for both of you. When I survey the classical scene today, what seems to me to be most popular—or at least most often performed and bought into by the larger general public—is what I call “classics lite” or “ambient classical,” music that is soft and relaxing, that doesn’t challenge people’s minds and emotions. Since both of you are so obviously dedicated to the exact opposite in music, what do you see as an antidote for this? In other words, is there any way you can see a future in which interesting music, emotionally played, once again becomes the norm rather than what young people refer to as “neo-classical chamber”?

THO: I am not a huge fan of labels, and it is especially impossible to label the time in which we are living. The music of all eras always contains works of great lasting meaning as well as shallow entertainment. That question has been with us throughout history. We have Bach vs. the lesser known Baroques, we have Beethoven vs. Spohr and Hummel, we have Schumann vs. Liszt and “the beat goes on.”

PK: For us the most important thing is to focus on music we find interesting and challenging, play it as well as we can, and put it out in the world. We rely on our instincts, training and experience to accomplish this. What happens afterwards, hmm…, well we can’t really control that, can we?

AML: I noticed that most of the works on this CD were either written for you, Tara, or commissioned directly by you. Yet I’m assuming that, because of your strong musical approach, you pick and choose the modern composers whom you approach to write for you. Is that correct?

THO: This CD was an evolutionary process. It stared with the idea of recording one of the first works Peggy and I performed together while we were finishing our graduate degrees at Stony Brook University. I then began to ask colleagues that I had worked with previously if they would be interested in writing pieces for us. These were composers whose work I fell in love with and really wanted to champion. They all said yes! We actually wound up with more pieces than we could fit on this CD and we hope to be doing a second one soon.

AML: Peggy, I can’t help but ask…how on earth did you get involved with the P.D.Q. Bach concerts? As busy as you are, I would think that you’d take a pass on something that is really a big musical joke! (I should mention that I love Schickele’s P.D.Q. Bach stuff and actually attended one of his concerts once, so I’m not speaking as someone who disapproves.)

A: Take a pass on working with Peter Schickele? The man is a total genius! I met him when I was performing some of his music here in New York. The rest is history, as they say. On the surface, P.D.Q. Bach concerts are entertaining and hilarious, but Peter Shickele’s underlying craft is impeccable. He is one of the finest musicians I know, and I have had a great time working with him and his incredibly talented musical cohorts.

AML: With both of you being so very busy, I wondered if you have much time, outside of a recording project like this, to perform together?

THO: We are both extremely busy, but we have played a lot together over many many years and always enjoy it. We will soon be starting on a new project with another colleague. Additionally, we have a chamber music group together that has recorded a few CDs. Having gone to school together, we share a similar background in our pedagogical studies. This makes the collaboration even more fun and rewarding. Having “grown up” together and honed our reflexes, I feel that we are really well matched. Additionally, we are great friends. It’s really fun!

PK: We are both extremely busy, but our paths cross often. Whenever we get a chance to play together, it’s like old friends meeting up. We just pick up where we left off and go from there.

AML: Thanks a million for your time! In closing, I would only say that I wish a record like yours would be nominated for a Grammy or a Pulitzer Prize in music, but I know better…it’s not commercial enough. But good luck to both of you in your future endeavors!

PK: Thank you so much for reviewing the CD so thoroughly and thoughtfully!

* * * * *

THE WAY THINGS GO / Righteous Babe (Randall Woolf); Crystal Shadows (Steven Mackey); Gaze (John Halle); All Sensation is Already Memory (Eric Moe); Share (Belinda Reynolds); The Way Things Go (Richard Festinger); Duo for Flute and Piano (Laura Kaminsky) / Tara Helen O’Connor, flautist; Margaret Kampmeier, pianist / Bridge 9467

A music critic friend of mine can’t understand my strong liking for many modern works. To him, great music pretty much ended in the 1920s, and any changes since then are just steps backwards. But I run into this attitude all the time. People either ask me how I can like the modern stuff since I so obviously love Monteverdi, Buxtehude, the Bachs, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Berlioz, Schumann, Verdi, Wagner, Brahms, Debussy etc, or—which to me is just as strange—they ask me how on earth I can listen to the “old stuff” if I enjoy so much music from Schoenberg and Stravinsky on forward.

The answer, of course, is what I listen for: 1) the music’s structure and, in the case of orchestral or choral works, texture, and 2) whether or not it communicates anything to me. The shape of the music doesn’t matter to me. I can get just as much out of the string quartets of Segerstam as I can out of Beethoven’s, and just as much out of the operas of Messiaen, Orff and Hindemith as I can out of the operas of Mozart and Verdi—in fact, probably a bit more. But if you don’t know music (and it embarrasses me to admit how many serious music lovers can’t read a score and don’t even know, for instance, that there are no high Cs in “Di quella pira” from Verdi’s Il Trovatore), you can’t tell if a piece is well written or not, because regardless of the style, the principles remain the same. The rest of it is simply whether or not the music moves you. If it sounds like an intellectual game I’m not much interested and I’ll write it off, but if it connects emotionally I’ll go out of my way to understand it.

Such is the case with this CD, admitted by flautist O’Connor on page 4 of the booklet as “a labor of love…recorded over several years with my dear friend Peggy Kampmeier.” And you can tell this from the first note of the first selection, a sort of bitonal tango-boogie (they come together in A for the main theme, but start to split around 2:04) titled Righteous Babe. Randall Woolf, the composer, studied privately with David Del Tredici and Joe Maneri. Most classical folks know who Del Tredici is, if only from his 1976 surprise hit Final Alice, but Joe Maneri is not so well known. Maneri (1927-2009) was a jazz composer, saxophonist and clarinetist, well known for his enthusiasm for the avant-garde. Righteous Babe is sort of in between jazz and classical, but decidedly leaning more towards the former in rhythm and drive. Woolf writes that it was composed for O’Connor and “chiefly concerned with avoiding the flowery and dainty side of the flute.” That’s putting it mildly. There’s a bit of Lew Tabackin and a touch of Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson here, and I found the whole piece exhilarating from start to finish.

The next several works are generally more abstract and less jazz-tinged in style, although the last movement of John Halle’s Gaze is marked “Rag: Raucous.” This is exactly the kind of music my tonal-loving friends don’t understand me liking, but as I’ve told them many times, listen for the structure. If the structure makes sense and is original in design, it’s good. If it’s original but poorly structured, it’s bad; if it’s neither original nor well structured, it’s rubbish. One need also keep in mind that some of these pieces, particularly Mackey’s Crystal Shadows, rely as much on the use of space between the notes as on the note sequence itself. There is also a certain amount of syncopation within this piece; it’s just not jazz syncopation. Halle’s Gaze is divided into three movements: “Always moving forward,” “Homage: Slow tango/Habanera” and “Rag: Raucous.” Halle uses rhythmic shifts here the way other composers might use thematic shifts; his theme keeps on developing throughout the first movement, but it rarely stays in the same rhythm or tempo. There is a certain amount of jazz “feel” around the 3:25 mark. The second movement, like the first, relies on tempo shifts which mirror the changes of dynamics and/or mood, but it is more playful and less serious-minded. Despite the allusion to ragtime, the last movement sounds to my ears more like something by Marius Constant than Joseph Lamb; even thought it stays mostly in A-flat, the piano part in particular plays around with the tonality (now playing a loud downward gliss, then playing crushed chords or altered chord positions) as the flute “gets lost” rhythmically before they “find” each other and come back together again.

I’ve had occasion to praise some of Eric Moe’s work in past reviews. All Sensation is Already Memory is a good piece—I liked it for the most part—although, to my ears, it’s not one of Moe’s most original works. Indeed, in style it closely resembled parts of Gaze, particularly the second movement. But as I say, it’s not a bad work at all, the piano part in particular having some very clever things to say. The work is in two parts, titled The Ungraspable Advance of the Past” and “Devouring the Future.” By contrast, Belinda Reynolds’ Share is an almost elegiac piece built around a repeated modal motif played by the piano whle the flute hovers above it playing a sparse but attractive melodic figure. I was not surprised to learn from the notes that Reynolds is an educator who helps children create music. The elegant simplicity of this piece may elude the listener who, so far in this recital, has been bombarded with interesting and novel effects, but my only (small) complaint about Share (which is played on the alto flute) is that I felt it went on a bit too long.

Richard Festinger, we are told, has led groups as a jazz musician in addition to his composition studies at the University of California in Berkeley. That being said, I enjoyed The Way Things Go tremendously for its clever working-out of short phrases, knit together in an almost awkward way that is strangely fascinating, but I heard no allusions to jazz in the score. The last of the three short movements has a quasi-Latin feel about it without really crossing over into that style of rhythm. Flutter-tonguing is used to enhance the mood as it was in Righteous Babe but also moments where the pianist plucks the strings. Festinger uses motor rhythms—but again, not jazz rhythms—to propel the music towards its conclusion.

The recital ends with Kaminsky’s Duo, which is the last piece written for this disc (2006). Curiously, the first of the three movements puts us back in the same kind of mood as Woolf’s opening piece, except that the rhythm is a bit more fractured here and there and not consistently moving forward. Indeed, the first movement comes to a standstill about a minute in so the solo flute can play an a capella solo for a few bars at a slower tempo, then the music is deconstructed when the piano returns, slowly unraveling and fragmenting itself into little 16th-note swirls alternated by the two instruments, then staccato notes which introduce an extempore section with greater fragmentation of the already minimal theme. This stops in the middle of nowhere before moving on to the more lyrical second movement, which sounds to me to be in an A mode, later shifting to B-flat. The last movement is all buoyant, nervous energy, once again using a stuttering ostinato rhythm in the keyboard, the music being “bound” thematically by the flute.

All in all, this is a fascinating recording, one well worth exploring, played with love and enthusiasm by two musicians who obviously enjoy what they’re doing.

— © 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Return to homepage OR

Read my book, From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed history of the intersection of classical music and jazz

When one discusses the great trumpet and cornet players in jazz, a long list of names come to mind, but when restricted to the late 1920s-early ‘30s only four names come up with any regularity: Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke, Bubber Miley and Red Nichols. There are strong, valid reasons why each of them are still remembered, particularly for this period of jazz, but one name that is seldom brought up except by serious collectors is that of Cladys “Jabbo” Smith.

When one discusses the great trumpet and cornet players in jazz, a long list of names come to mind, but when restricted to the late 1920s-early ‘30s only four names come up with any regularity: Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke, Bubber Miley and Red Nichols. There are strong, valid reasons why each of them are still remembered, particularly for this period of jazz, but one name that is seldom brought up except by serious collectors is that of Cladys “Jabbo” Smith. impromptu cadenza that sounds a bit like Armstrong’s on West End Blues but played at warp speed. Like Armstrong, Smith utilizes initial note and terminal vibrato—something he held back from in his earlier recordings—but he also plays much more wild solos, staying up almost consistently in the top third of his range and building his solos around rather wild triplet figures. In his early sessions he was lucky enough to obtain the services of the great Omer Simeon, Jelly Roll Morton’s favorite clarinetist, a superb technician with a fine ear and first-class reading skills who could weave appropriate counterpoint around Smith’s sometimes Baroque fantasies. In the later recordings made from March 30 on, Simeon was replaced by the so-so alto saxist George James, but the trade-off was that the merely competent pianist Cassino Simpson was replaced by an excellent, underrated player named Earl Frazier.

impromptu cadenza that sounds a bit like Armstrong’s on West End Blues but played at warp speed. Like Armstrong, Smith utilizes initial note and terminal vibrato—something he held back from in his earlier recordings—but he also plays much more wild solos, staying up almost consistently in the top third of his range and building his solos around rather wild triplet figures. In his early sessions he was lucky enough to obtain the services of the great Omer Simeon, Jelly Roll Morton’s favorite clarinetist, a superb technician with a fine ear and first-class reading skills who could weave appropriate counterpoint around Smith’s sometimes Baroque fantasies. In the later recordings made from March 30 on, Simeon was replaced by the so-so alto saxist George James, but the trade-off was that the merely competent pianist Cassino Simpson was replaced by an excellent, underrated player named Earl Frazier. The Rhythm Aces records swung, but in an odd sort of way. Although it took Dizzy Gillespie to fully break the mold between the jazz rhythm of Armstrong and that of future jazz, on these 1929 recordings Jabbo Smith is already pushing the envelope. Small wonder that, despite Williams’ promotion for them in the black newspaper The Chicago Defender, they sold fairly poorly and were soon forgotten…except by a handful of musicians, among them young Roy Eldridge. Eventually the younger Eldridge met his idol in person, but that first encounter wasn’t a very happy one for him. By Eldridge’s own account, “Jabbo Smith caught me one night and turned me every way but loose…he wore me out …He knew a lot of music and changes.”

The Rhythm Aces records swung, but in an odd sort of way. Although it took Dizzy Gillespie to fully break the mold between the jazz rhythm of Armstrong and that of future jazz, on these 1929 recordings Jabbo Smith is already pushing the envelope. Small wonder that, despite Williams’ promotion for them in the black newspaper The Chicago Defender, they sold fairly poorly and were soon forgotten…except by a handful of musicians, among them young Roy Eldridge. Eventually the younger Eldridge met his idol in person, but that first encounter wasn’t a very happy one for him. By Eldridge’s own account, “Jabbo Smith caught me one night and turned me every way but loose…he wore me out …He knew a lot of music and changes.”

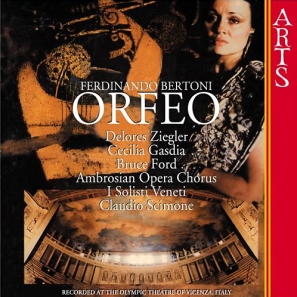

As it is, I can’t recommend it over the mid-1990s recording on Arts Music with Delores Ziegler (Orfeo), Cecilia Gasdia (Euridice) and Bruce Ford (Imeneo) with the Solisti Veneti—a sort of mid-period HIP orchestra, not as whiny-sounding as the Ensemble Lorenzo da Ponte—conducted by Claudio Scimone, who actually, really uses legato phrasing. In addition, Ziegler presents us with a real, complex character, not just a nice singing job—although sheerly in terms of singing, she has it all over Genaux. Her voice is richer, her tone coloring vastly superior, and she sings the trills that Genaux simply skips over. (The presence of the great Bruce Ford as Imeneo speaks for itself…here was a master tenor in a nice piece of luxury casting for a throwaway role.) Even the little bridge passages for the strings sound better in Scimone’s version, and overall the opera just sounds more Italian, if you know what I mean. This new recording is, quite simply, wrong-headed in execution and hard to listen to, a real disaster.

As it is, I can’t recommend it over the mid-1990s recording on Arts Music with Delores Ziegler (Orfeo), Cecilia Gasdia (Euridice) and Bruce Ford (Imeneo) with the Solisti Veneti—a sort of mid-period HIP orchestra, not as whiny-sounding as the Ensemble Lorenzo da Ponte—conducted by Claudio Scimone, who actually, really uses legato phrasing. In addition, Ziegler presents us with a real, complex character, not just a nice singing job—although sheerly in terms of singing, she has it all over Genaux. Her voice is richer, her tone coloring vastly superior, and she sings the trills that Genaux simply skips over. (The presence of the great Bruce Ford as Imeneo speaks for itself…here was a master tenor in a nice piece of luxury casting for a throwaway role.) Even the little bridge passages for the strings sound better in Scimone’s version, and overall the opera just sounds more Italian, if you know what I mean. This new recording is, quite simply, wrong-headed in execution and hard to listen to, a real disaster.

It was a high-pitched voice, very sweet in sound and completely unlike any other contemporary pop singer I had ever heard. I thought it was a woman singing…I was, in fact, quite surprised to learn that it was a man. I looked at the album cover and saw a faded black-and-white photo of a freckle-faced boy with the single word, Harry, next to it. That was my introduction to Harry Nilsson. I listened to the entire album in one sitting; each song seemed as good if not better than the last. When it was finished, I felt as if there was someone—this singer-songwriter, at least—who understood what it was like to feel alienated.

It was a high-pitched voice, very sweet in sound and completely unlike any other contemporary pop singer I had ever heard. I thought it was a woman singing…I was, in fact, quite surprised to learn that it was a man. I looked at the album cover and saw a faded black-and-white photo of a freckle-faced boy with the single word, Harry, next to it. That was my introduction to Harry Nilsson. I listened to the entire album in one sitting; each song seemed as good if not better than the last. When it was finished, I felt as if there was someone—this singer-songwriter, at least—who understood what it was like to feel alienated. these. By this time I had seen the film Midnight Cowboy and heard the song Everybody’s Talkin’. Still in college, I heard the music from Nilsson’s animated film The Point, which I liked less, but was still a fan. I learned, by this time, that Nilsson had started out making demo records for songwriter Scott Turner in 1962, then wrote some songs (including one for Little Richard and three for Phil Spector) through which he met and befriended publisher Perry Botkin, Jr. All through this period he worked at a bank on computers—remember, these were the days when “computer” meant something six feet high and four feet across, with huge digital tape reels on them, set aside in a dustproof room (think of the computer Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey), not something on a desk. But Nilsson had an office of his own. He sang just one live performance in tandem with another singer, was petrified and hated the experience, but Botkin was still able to promote Nilsson as a singer. He introduced him to composer-arranger George Tipton, who acted as Nilsson’s music director on his first three RCA Victor albums (including Harry). Tipton personally invested his life’s savings, $2,500, to record four songs with Nilsson which he was able to sell to Tower Records. Due to these demos, Tipton wangled a contract with RCA and history was made.

these. By this time I had seen the film Midnight Cowboy and heard the song Everybody’s Talkin’. Still in college, I heard the music from Nilsson’s animated film The Point, which I liked less, but was still a fan. I learned, by this time, that Nilsson had started out making demo records for songwriter Scott Turner in 1962, then wrote some songs (including one for Little Richard and three for Phil Spector) through which he met and befriended publisher Perry Botkin, Jr. All through this period he worked at a bank on computers—remember, these were the days when “computer” meant something six feet high and four feet across, with huge digital tape reels on them, set aside in a dustproof room (think of the computer Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey), not something on a desk. But Nilsson had an office of his own. He sang just one live performance in tandem with another singer, was petrified and hated the experience, but Botkin was still able to promote Nilsson as a singer. He introduced him to composer-arranger George Tipton, who acted as Nilsson’s music director on his first three RCA Victor albums (including Harry). Tipton personally invested his life’s savings, $2,500, to record four songs with Nilsson which he was able to sell to Tower Records. Due to these demos, Tipton wangled a contract with RCA and history was made. something indefinably beautiful about them; they have a certain timeless quality. At the time they were released, Time magazine referred to that genre of music as “salon rock.” I suppose that’s as good a definition as any, but to me the “rock” element is so gentle and innocuous that it isn’t even noticeable most of the time. When Nilsson died of heart failure in 1994, not quite aged 53, it came as a bit of a shock to me, but by this time he had become much more identified with the songs Without You and Coconut in the eyes of the public. I miss that early part of you, Harry, and I wish you hadn’t deserted your principles and style. It was what made you unique.

something indefinably beautiful about them; they have a certain timeless quality. At the time they were released, Time magazine referred to that genre of music as “salon rock.” I suppose that’s as good a definition as any, but to me the “rock” element is so gentle and innocuous that it isn’t even noticeable most of the time. When Nilsson died of heart failure in 1994, not quite aged 53, it came as a bit of a shock to me, but by this time he had become much more identified with the songs Without You and Coconut in the eyes of the public. I miss that early part of you, Harry, and I wish you hadn’t deserted your principles and style. It was what made you unique.

and Willie Cook replacing Bailey—who were able to play like him, at least when he wrote out the improvisations, scored them for five trumpets, and led the section himself. The effect was stunning if a little messy: the 1940s Gillespie band always seemed to have slight intonation problems, particularly in the reed section. But in the end it didn’t matter because their playing was just so exciting. I can still recall, as an 18-year-old, buying the RCA Victor Vintage LPs The Be-Bop Era and Dizzy Gillespie, and thrilling to such mind-boggling pieces as Ow!, Stay on It, Oop-Pop-A-Da and Cool Breeze (on the former) and many more on the latter (Lover Come Back to Me, Jumpin’ With Symphony Sid, Hey Pete! Let’s Eat Mo’ Meat, Woody’n You, Ool-Ya-Koo, Duff Capers, Guarachi Guaro and that well-known bebop fairy tale, In the Land of Oo-Bla-Dee). For one raised on the more traditional swing bands of Ellington, Miller, Basie and Tommy Dorsey, the Gillespie band hit me like a ton of bricks. I couldn’t get enough of them; they were febrile in a way that was almost beyond words, even on studio recordings, the band fairly exploding from the grooves of the records and Dizzy riding above the fray like some high, wailing banshee Lord of the Rings. It fairly blew my 18-year-old mind.

and Willie Cook replacing Bailey—who were able to play like him, at least when he wrote out the improvisations, scored them for five trumpets, and led the section himself. The effect was stunning if a little messy: the 1940s Gillespie band always seemed to have slight intonation problems, particularly in the reed section. But in the end it didn’t matter because their playing was just so exciting. I can still recall, as an 18-year-old, buying the RCA Victor Vintage LPs The Be-Bop Era and Dizzy Gillespie, and thrilling to such mind-boggling pieces as Ow!, Stay on It, Oop-Pop-A-Da and Cool Breeze (on the former) and many more on the latter (Lover Come Back to Me, Jumpin’ With Symphony Sid, Hey Pete! Let’s Eat Mo’ Meat, Woody’n You, Ool-Ya-Koo, Duff Capers, Guarachi Guaro and that well-known bebop fairy tale, In the Land of Oo-Bla-Dee). For one raised on the more traditional swing bands of Ellington, Miller, Basie and Tommy Dorsey, the Gillespie band hit me like a ton of bricks. I couldn’t get enough of them; they were febrile in a way that was almost beyond words, even on studio recordings, the band fairly exploding from the grooves of the records and Dizzy riding above the fray like some high, wailing banshee Lord of the Rings. It fairly blew my 18-year-old mind.

the musically meticulous Arturo Toscanini allowed him to do some things he would never have accepted a decade or so later. His only complaint was that Chaliapin was “marking” his part—singing sotto voce—in rehearsal. “Signor Chaliapin!” cried the Maestro. “Unfortunately, we have not had the pleasure of hearing you sing at the Imperial Russian Opera. Could you please sing in full voice so that we may judge how you will do this role?” Chaliapin sang out. Toscanini was bowled over. Years later, when the bass returned to the Metropolitan Opera after a 13-year hiatus, one of the tenors he sang with was Beniamino Gigli, noted for having the most beautiful and perfectly-placed voice of any Italian singer. Gigli later said that “Chaliapin’s singing was as great as his acting. His voice was beautiful in texture, perfectly produced, thrilling in range and power; his vocalism was an outstanding exhibition of breath control, tonal production and phrasing.” This can be easily borne out by his recording of Anton Rubinstein’s Persian Love Song No. 9, subtitled The Turbulent Waters of Kur. Made in 1931 when he was 58 years old and had been using his voice in a very hard way for at least 33 years, it features a final chorus sung entirely in a high, soft head voice, what voice teachers refer to as a fil di voce, and both his pitch and his breath control are perfect. It could easily ne held up as a model of bel canto singing from an artist who was, if anything, anti-bel canto in his general approach.

the musically meticulous Arturo Toscanini allowed him to do some things he would never have accepted a decade or so later. His only complaint was that Chaliapin was “marking” his part—singing sotto voce—in rehearsal. “Signor Chaliapin!” cried the Maestro. “Unfortunately, we have not had the pleasure of hearing you sing at the Imperial Russian Opera. Could you please sing in full voice so that we may judge how you will do this role?” Chaliapin sang out. Toscanini was bowled over. Years later, when the bass returned to the Metropolitan Opera after a 13-year hiatus, one of the tenors he sang with was Beniamino Gigli, noted for having the most beautiful and perfectly-placed voice of any Italian singer. Gigli later said that “Chaliapin’s singing was as great as his acting. His voice was beautiful in texture, perfectly produced, thrilling in range and power; his vocalism was an outstanding exhibition of breath control, tonal production and phrasing.” This can be easily borne out by his recording of Anton Rubinstein’s Persian Love Song No. 9, subtitled The Turbulent Waters of Kur. Made in 1931 when he was 58 years old and had been using his voice in a very hard way for at least 33 years, it features a final chorus sung entirely in a high, soft head voice, what voice teachers refer to as a fil di voce, and both his pitch and his breath control are perfect. It could easily ne held up as a model of bel canto singing from an artist who was, if anything, anti-bel canto in his general approach. Chaliapin was not being willful, but had clearly and meticulously thought all of his effects out beforehand and was, as he was wont to say, a “serious artist.” When rehearsing the opera at La Scala, Toscanini tried to show Chaliapin how to stand on stage as the devil. “You fold your arms in front of you, you know, and look evil and menacing.” “Thank you for your suggestion, maestro,” Chaliapin replied, “but may I try it my way and see if you like it?” Toscanini agreed. Chaliapin transformed his body into a twisting, demonic thing, menacing even in the confines of the rehearsal area. Toscanini was convinced. Years later, when he went to see Chaliapin sing Boris Godunov, he told critic B.H. Haggin that he was perfection. “If I had been a woman, I would have kissed him!” said Toscanini. Rare praise indeed from a man thought of as an inflexible martinet, but chaliapin returned the compliment. In his memoir Man and Mask (1932), he claimed that there were only two truly great conductors in his opinion, Toscanini and Sergei Rachmaninov.

Chaliapin was not being willful, but had clearly and meticulously thought all of his effects out beforehand and was, as he was wont to say, a “serious artist.” When rehearsing the opera at La Scala, Toscanini tried to show Chaliapin how to stand on stage as the devil. “You fold your arms in front of you, you know, and look evil and menacing.” “Thank you for your suggestion, maestro,” Chaliapin replied, “but may I try it my way and see if you like it?” Toscanini agreed. Chaliapin transformed his body into a twisting, demonic thing, menacing even in the confines of the rehearsal area. Toscanini was convinced. Years later, when he went to see Chaliapin sing Boris Godunov, he told critic B.H. Haggin that he was perfection. “If I had been a woman, I would have kissed him!” said Toscanini. Rare praise indeed from a man thought of as an inflexible martinet, but chaliapin returned the compliment. In his memoir Man and Mask (1932), he claimed that there were only two truly great conductors in his opinion, Toscanini and Sergei Rachmaninov. happy to sing Pimen and watch Chaliapin as Boris. He was a superlative actor, so compelling that only my professional experience and perfect knowledge of my role saved me time and again from missing cues, so absorbed was I in watching him act.” Lotte Lehmann, who sang Margherita opposite his Faust in Gounod’s opera, recalled that “The impression he made on me was indescribable. After the scene when Mephistopheles challenges nature to help him in the corruption of the innocent Marguerite, he stood like a tree, perfectly still against the background. He gave the impression of being a tree, and then quite suddenly, he had disappeared, as if blown away. I did not see him sneak off, and I have no idea how he managed it, but it was like black magic. At the end of the act, in the embrace, a tall figure appeared above me that twisted its way along the window like some frightful spider, seeming to encircle Faust and me. An indefinable terror made me go cold. This was no longer opera, this was turned into some terrible reality. And when the curtain came down, and Mephostipheles changed back into Chaliapin, I breathed a sigh of relief.”

happy to sing Pimen and watch Chaliapin as Boris. He was a superlative actor, so compelling that only my professional experience and perfect knowledge of my role saved me time and again from missing cues, so absorbed was I in watching him act.” Lotte Lehmann, who sang Margherita opposite his Faust in Gounod’s opera, recalled that “The impression he made on me was indescribable. After the scene when Mephistopheles challenges nature to help him in the corruption of the innocent Marguerite, he stood like a tree, perfectly still against the background. He gave the impression of being a tree, and then quite suddenly, he had disappeared, as if blown away. I did not see him sneak off, and I have no idea how he managed it, but it was like black magic. At the end of the act, in the embrace, a tall figure appeared above me that twisted its way along the window like some frightful spider, seeming to encircle Faust and me. An indefinable terror made me go cold. This was no longer opera, this was turned into some terrible reality. And when the curtain came down, and Mephostipheles changed back into Chaliapin, I breathed a sigh of relief.” But the best summary of this great and gifted artist came from the eminent Russian critic Alexander Amphiteatrov. “Chaliapin is the only one who, when I listen to him, never makes me feel that the impression I have of art suffers a painful comparison between past and present; on the contrary, the more I listen, the more convinced I become that this is new, fresh and infinitely more vigorous than anything that has gone before on the lyric stage. This is an artist such as has never been before, the begetter of a new force in art, a reformer creating a new school…when you go to hear Chaliapin, you don’t even remember that you have gone to hear ‘a bass.’ What you want is Chaliapin, not his ability to sing loud or soft notes in the order required by the part, but his extraordinary talent for thinking in sounds—a wonderful new revelation which the arrival of this strange man has brought to singers.”

But the best summary of this great and gifted artist came from the eminent Russian critic Alexander Amphiteatrov. “Chaliapin is the only one who, when I listen to him, never makes me feel that the impression I have of art suffers a painful comparison between past and present; on the contrary, the more I listen, the more convinced I become that this is new, fresh and infinitely more vigorous than anything that has gone before on the lyric stage. This is an artist such as has never been before, the begetter of a new force in art, a reformer creating a new school…when you go to hear Chaliapin, you don’t even remember that you have gone to hear ‘a bass.’ What you want is Chaliapin, not his ability to sing loud or soft notes in the order required by the part, but his extraordinary talent for thinking in sounds—a wonderful new revelation which the arrival of this strange man has brought to singers.” excerpts from Gounod’s Faust, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Mozart and Salieri, and his signature role, Boris Godunov. In 1931 he made two versions of the same film, Don Quixote, in French and English. The supporting casts were not the same. Although the print of the English version is in better condition and the supporting cast superior, I prefer hearing Chaliapin speak and sing in French which he is more comfortable with, but both versions show what a great actor he was. But why Don Quixote? Or, more to the point, why nothing from Boris Godunov? Yes, it’s nice to hear him do the role live—there’s an extra dimension to both the Clock Scene and the farewell, prayer and death of Boris that are missing from his commercial recordings—but do you mean to tell me that no one had the money or the willingness to film even a couple of scenes from Boris with him? I find that hard to believe. In the meantime he became one of the most famous and sought-after vocal recitalists in the world, promoted in the U.S. by Sol Hurok. Sometime in the early 1930s he developed kidney problems, for which he went annually to health spas to try to cure, but it eventually caught up with him. He died on April 12, 1938 at the age of 65.

excerpts from Gounod’s Faust, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Mozart and Salieri, and his signature role, Boris Godunov. In 1931 he made two versions of the same film, Don Quixote, in French and English. The supporting casts were not the same. Although the print of the English version is in better condition and the supporting cast superior, I prefer hearing Chaliapin speak and sing in French which he is more comfortable with, but both versions show what a great actor he was. But why Don Quixote? Or, more to the point, why nothing from Boris Godunov? Yes, it’s nice to hear him do the role live—there’s an extra dimension to both the Clock Scene and the farewell, prayer and death of Boris that are missing from his commercial recordings—but do you mean to tell me that no one had the money or the willingness to film even a couple of scenes from Boris with him? I find that hard to believe. In the meantime he became one of the most famous and sought-after vocal recitalists in the world, promoted in the U.S. by Sol Hurok. Sometime in the early 1930s he developed kidney problems, for which he went annually to health spas to try to cure, but it eventually caught up with him. He died on April 12, 1938 at the age of 65.