Not one friend my age, when growing up, understood my youthful passion for the music of Glenn Miller. It wasn’t that he was an enigma, or that his band belonged to another generation, although that probably had some play in it. The real reason was that they didn’t hear what I heard: the workings of a superior mind, both in terms of musical construction and orchestration, in the often ephemeral popular tunes of his day.

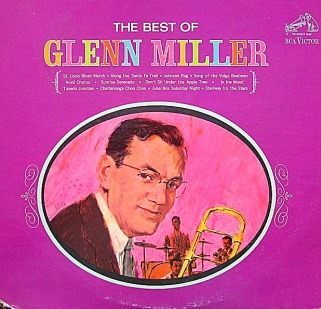

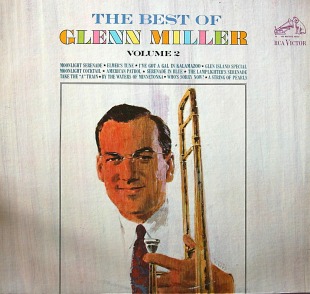

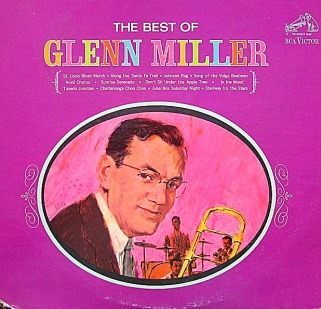

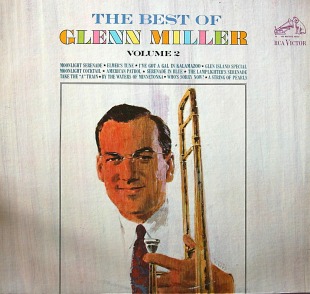

By the time I was 18 years old, I had a massive Glenn Miller collection. It had started with the two “Best of” albums that RCA Victor issued in 1965 but then mushroomed into the three single-LP releases of “Glenn Miller on the Air,” the two five-LP deluxe fold-out book sets of a mixture of unusual commercial recordings and live broadcasts, a couple of RCA Camden releases of commercial discs, the five-LP set of his Army Air Force band, two albums’ worth of his film soundtracks for 20th Century Fox and another, three-LP deluxe RCA set of rare broadcasts. To say I was hooked would be putting it mildly.

Of course, in time I fell away from most of this, realizing that along with the pearls in these collections came the chaff as well. Perhaps my biggest disillusionment was to hear, years later, the Chesterfield broadcasts that the band gave with the Andrews Sisters. Never had I looked forward to a Miller set as much, but his arrangements for the Andrews were routine and predictable, sounding more like generic charts than anything played by the Miller band. I was sorely disappointed.

But what exactly was it that drew me like a moth to a flame when it came to Glenn Miller? Several things. First, and probably most obvious, was that irresistible clarinet-led reed section blend, which even as stringent a critic as Gunther Schuller called the most hypnotic sound in Western music. But if that were all, I would have been just as impressed by the Miller-imitation bands led by Bob Chester and Ralph Flanagan—yet I wasn’t, because there was more. There was his use of ooh-wah brass, not an original device in itself but masterly in the way he used them. There were his brass smears, his absolutely brilliant juxtaposition of reeds and brass, his use of a completely interlocking rhythm section that played as if by one man with four instruments (Schuller also mentioned this), and—last but not least—his innovative and, I would say, unique use of rhythmic and harmonic devices that “built” up each arrangement and made them perfect little jewels that had a beginning, a middle, and an end, just like a good piece of classical music.

As the years and decades passed, I realized that I was not the only one to notice these things. Schuller, a fairly unpleasant egotist who nevertheless had a fine musical mind, was probably the most noted jazz scholar to agree with me, but I had the actions and attitudes of others who I either discussed Miller with personally or read about in articles and books who felt about him the same way I did, to wit:

- Classical conductor Keith Lockhart, current director of the Boston Pops Orchestra but former associate conductor of both the Cincinnati Symphony and Cincinnati Pops orchestras. When he was asked to put on a concert of Miller’s music with the latter, he had no more than a passing acquaintance with Miller’s music, probably by hearing In the Mood and Chattanooga Choo-Choo a few times. But when he started digging into Miller’s scores of such old 1920s tunes like Runnin’ Wild, My Blue Heaven and Pagan Love Song, he was literally stunned by the technical difficulties these scores called for; and, upon hearing Miller’s original recordings, was more than a little shocked that he could get young musicians of his day, many without any real formal training, to play these scores.

- Jazz clarinetist Buddy de Franco who was, for a time, leader of the Glenn Miller “ghost” orchestra during the 1960s and early ‘70s. When I saw him leading the Miller band in one concert, I went up and talked to him afterwards. He told me that, as a member of the rival Tommy Dorsey orchestra in the 1940s, he thought that the Sy Oliver charts he played with Dorsey were superior to Miller’s, but that now he was actually involved in performing them he was amazed at their “harmonic subtlety, rhythmic ingenuity and overall musical concept”—and he agreed with me that, although he liked playing pop hits of the day in the “Miller style,” no one could arrange the music with Miller’s deep knowledge and understanding of what made it tick.

- The late jazz pianist Jack Reilly, who worked with the Modernaires (Miller’s vocal group) for a few years and, like de Franco, was startled by the musical sophistication of Miller’s original scores when he actually had to play them.

- Vet Boswell, the last surviving member of the legendary Boswell Sisters jazz singing group, who told me on the phone how Miller, hired as second trombonist on one session, was able in “less than 15 minutes” to completely revamp the arrangement of Alexander’s Ragtime Band from a fairly mundane thing into a masterpiece of musical construction, including a completely original introduction and a two-trombone chorus (played with Tommy Dorsey) that had brass punctuations throughout. (The discographies all list Chuck Campbell as second trombone on this session, but when I told Vet that she exploded at me. “Don’t you think I’d know Glenn Miller when I saw him?” she snapped. “Of COURSE it was Glenn Miller!”)

- Jazz legend Bobby Hackett, who played both cornet and guitar with Miller’s band in its last two years, told Whitney Balliett of The New Yorker that Miller was a “genius” at being able to tweak a score, even those not written by him. “He’d listen to a new [arrangement] and suggest a slightly different voicing or a different background behind a solo, and the whole thing would fall suddenly into place.”

- Louis Armstrong used to carry around a reel-to-reel tape of Glenn Miller recordings and another of Tchaikovsky symphonies, which he played for himself all the time when on the road.

But Miller only arrived at his final form of 1938-44 by trial and error, although the recorded evidence proves that he was an innovator early on. While with the Ben Pollack Orchestra of the late 1920s, he was for some reason only occasionally allowed to write real jazz arrangements, though he did (Waitin’ for Katie and Yellow Dog Blues are two of the best). Once the “society” jazz band of Roger Wolfe Kahn became a big hit with its smooth-but-swinging arrangements that used a few strings in the mix, Pollack sent Miller to go listen to that band for a few nights and come up with some similar arrangements, which he did (i.e., Buy Buy for Baby). His real first liberation came when working as a free-lancer for Red Nichols and his Five Pennies in 1928-32. It was during this period that Miller came up with one innovative score after another, using a multitude of techniques such as an expanded Dixieland sound (Indiana, Dinah), a prototype Big Band sound using eight instruments like a full orchestra (Rose of Washington Square) and even using Benny Goodman’s clarinet like a flute fluttering above the winds, later to move into a boogie-woogie beat for Carolina in the Morning. Nothing seemed too daring or original for him; he just kept trying out one new idea after another.

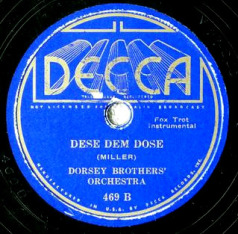

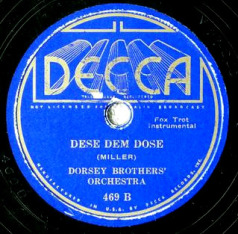

By the time he worked with Tommy Dorsey and the Boswell Sisters in 1934, Glenn was already chief arranger and second trombone with the then-full-time Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra. Tommy especially liked Miller’s expanded-Dixieland sound, so that’s what he stuck with, writing a full-band version of King Oliver’s Dippermouth Blues, a cute original tune called Dese Dem Dose, Jelly Roll Morton’s Milenberg Joys, and a six-minute arrangement of Honeysuckle Rose. By the time the Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra broke up in 1935, Miller’s reputation as a jazz arranger had grown substantially. One story that trombonist-vocalist Jack Teagarden never tired of telling until his dying day was how Miller wrote a completely new extended introduction to Basin Street Blues for one of Jack’s Charleston Chasers sessions, the section that begins “Won’t you come along with me…Down the Mississippi…We’ll take a trip to the land of dreams…Steamin’ down the river to New Orleans.” Teagarden always felt that Miller should be listed as co-composer of Spencer Williams’ song, since everyone in the world sang or played that intro as part of the tune forever and ever, but Miller modestly waved it away as just another day’s work.

By the time he worked with Tommy Dorsey and the Boswell Sisters in 1934, Glenn was already chief arranger and second trombone with the then-full-time Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra. Tommy especially liked Miller’s expanded-Dixieland sound, so that’s what he stuck with, writing a full-band version of King Oliver’s Dippermouth Blues, a cute original tune called Dese Dem Dose, Jelly Roll Morton’s Milenberg Joys, and a six-minute arrangement of Honeysuckle Rose. By the time the Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra broke up in 1935, Miller’s reputation as a jazz arranger had grown substantially. One story that trombonist-vocalist Jack Teagarden never tired of telling until his dying day was how Miller wrote a completely new extended introduction to Basin Street Blues for one of Jack’s Charleston Chasers sessions, the section that begins “Won’t you come along with me…Down the Mississippi…We’ll take a trip to the land of dreams…Steamin’ down the river to New Orleans.” Teagarden always felt that Miller should be listed as co-composer of Spencer Williams’ song, since everyone in the world sang or played that intro as part of the tune forever and ever, but Miller modestly waved it away as just another day’s work.

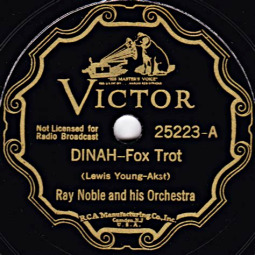

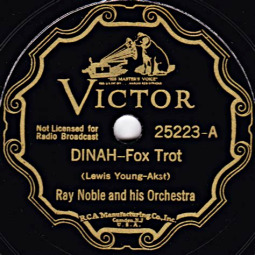

The Dorsey Brothers experience led directly to his being hired by famed British bandleader Ray Noble when the latter came to New York in 1935 and landed a prestigious spot in the Rainbow Room of the newly-built RCA Building. Miller was asked to recruit musicians for his orchestra, no expense to be spared. Glenn responded with some of the finest session men in New York at the time: lead trumpeter Charlie Spivak, jazz trumpeter Sterling Bose, trombonist Will Bradley, clarinetist Johnny Mince, pianist Claude Thornhill and legendary Chicago jazz saxist Bud Freeman. It was a band with five future bandleaders in it (Miller, Spivak, Bradley, Thornhill and Freeman). Given some freedom by Noble to write however he wished, Miller turned out some outstanding charts, again showing great  diversity in approach: Chinatown, My Chinatown; Dinah; and a tongue-in-cheek arrangement of Bugle Call Rag that used quotes from both a sailor song and Ravel’s Bolero. In one of his arrangements for Noble, Way Down Yonder in New Orleans, he first came up with a device that he would re-use several times with his famous civilian band: the riff that starts out softly, almost a whisper, but then gradually increases until he brings it to a roaring climax and then breaks it off to proceed to either the next theme, a variation on the theme, or (as in the case of In the Mood) a diminuendo in the coda. And when Bunny Berigan, Benny Goodman’s star jazz trumpeter, wanted to make his first band records, Miller was the one he turned to. Glenn wrote two brilliant arrangements for Berigan, Solo Hop and In a Little Spanish Town, in one night and recorded them the next day.

diversity in approach: Chinatown, My Chinatown; Dinah; and a tongue-in-cheek arrangement of Bugle Call Rag that used quotes from both a sailor song and Ravel’s Bolero. In one of his arrangements for Noble, Way Down Yonder in New Orleans, he first came up with a device that he would re-use several times with his famous civilian band: the riff that starts out softly, almost a whisper, but then gradually increases until he brings it to a roaring climax and then breaks it off to proceed to either the next theme, a variation on the theme, or (as in the case of In the Mood) a diminuendo in the coda. And when Bunny Berigan, Benny Goodman’s star jazz trumpeter, wanted to make his first band records, Miller was the one he turned to. Glenn wrote two brilliant arrangements for Berigan, Solo Hop and In a Little Spanish Town, in one night and recorded them the next day.

It was during his stint with the Noble band in 1935-36 that Miller first began toying with the ooh-wah brass (in modest form), wrote a song called Now I Lay Me Down to Weep that was, oddly, never recorded, but which he later turned into his theme song, Moonlight Serenade, and also started to think of a clarinet leading the reeds. The latter was suggested to him by a similar voicing used by the then-famous Isham Jones Orchestra, except that the Jones band used an alto sax lead over tenors and a baritone. But he wouldn’t really start using it until a few months into leading his own first big band in 1937, and then only sporadically.

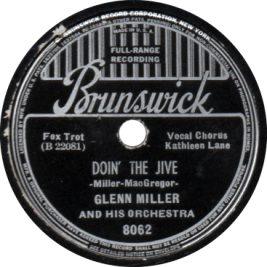

Schuller blasted the dance-crazed public for not recognizing and embracing Miller’s “more advanced approach” over the bland, often stock arrangements played by his former employer Tommy Dorsey in 1935-37, but the problems with the first Miller band ran deeper than that. By his own (later) admission, Miller didn’t really have good enough musicians. When they made their first Decca recording session, he was forced to hire high-priced ringers like famed New Orleans clarinetist Irving Fazola and his former Noble bandmates Charlie Spivak and Sterling Bose to make them sound better, and even then they were only able to record two songs in five hours and neither side was very distinctive-sounding. Yet even by his own account, he kept changing personnel and working on the band, and by later in the year they were turning out some pretty impressive records. Schuller particularly liked his complex arrangement of I Got Rhythm and a Miller original called Community Swing, but there were also some outstanding medium-tempo bouncing vocals by an excellent singer named Kathleen “Kitty” Lane, who unfortunately was not hired by Miller for his more famous orchestra, and later on  there was a very interesting uptempo swing piece that vacillated between minor and major (the middle eight switches to major for the first four bars, then incorporates not one but two key changes in the next two bars with a return to the minor in the final two), included a vocal chorus by Lane, one by the band and a comical spoken exchange between tenor saxist Jerry Jerome and Miller, called Doin’ the Jive. I never could understand why this tune was not revived by the more famous band for Marion Hutton, Tex Beneke and Miller. It was a perfect vehicle…but perhaps he felt the minor-major switches were too complex for his listeners.

there was a very interesting uptempo swing piece that vacillated between minor and major (the middle eight switches to major for the first four bars, then incorporates not one but two key changes in the next two bars with a return to the minor in the final two), included a vocal chorus by Lane, one by the band and a comical spoken exchange between tenor saxist Jerry Jerome and Miller, called Doin’ the Jive. I never could understand why this tune was not revived by the more famous band for Marion Hutton, Tex Beneke and Miller. It was a perfect vehicle…but perhaps he felt the minor-major switches were too complex for his listeners.

But there was a darker side to this early band: most of the jazz soloists he hired were hardcore alcoholics who either messed up on gigs or missed them entirely. This didn’t sit at all well with the highly disciplined, almost drill-sergeant-like Miller. He gave the band two weeks’ notice on New Year’s Even of 1937. When the band got stuck in a deep winter snowstorm in January 1938 and couldn’t make their next gig, Miller pulled the plug and gave it up. His good friend, jazz critic George T. Simon, got Jerry Jerome a job as jazz tenor saxist with Red Norvo’s band, a move that Miller viewed as a stab in the back, but as Simon put it, “You’re my friend, but so is Jerry. He has a family and needs to eat. I felt it was my duty to help him, and I’d have done the same for you if you were the one in need of help.”

Miller spent two months re-thinking his position and decided to try again, but with a different group of musicians and a different musical mindset. For one thing, his new band was not going to vacillate between two-beat jazz, which he had been raised on (the Dixieland influence) and four-beat jazz, which was clearly more popular. For another, he was not going to mix musical styles but try to create a uniform “sound” that would permeate all of his arrangements whether ballads or jump tunes. And thirdly, although he would audition a large number of musicians and pick the ones who were the best readers and the most technically proficient, he would check out their backgrounds and make sure that none of them were alcoholics or pot smokers. The only holdovers from the earlier band were alto saxist and clarinetist Hal McIntyre, his close friend Chalmers “Chummy” MacGregor on piano and Rolly Bundock on bass. The last-named was kind of a drag since he couldn’t really swing, but Miller kept working with him and finally got him to play with some lift in the rhythm. His first drummer with the new band, who stayed with him several months, was the flat-footed Bob Spangler, replaced in December by the only-slightly-better Cody Sandifer. Interestingly, although he had down-home-folksy tenor saxist and singer Tex Beneke and his most famous balladeer, Ray Eberle, with him from the start, his first “girl singer” was Gail Reese, who was only slightly less good than Kathleen Lane and who sounded nothing like Marion Hutton.

But where did the perennially broke Miller get the funds to re-start his band? Believe it or not, from his old boss Tommy Dorsey. Dorsey, like his former Ben Pollack bandmate Benny Goodman, really did believe in Miller’s talent as an arranger and his discipline as a builder of orchestras to be a success, yet there was more to it than that. Tommy was a bit of a gambler and thought of himself as a hotshot businessman who could outsmart the agents and executives who ran the music business. He was so sure that Miller would be a success this time that he thought Glenn would cut him in on the profits of the band when they hit it big. It came as an unpleasant shock to him when Miller, through his agency at the time (the powerful firm of Rockwell-O’Keefe) mailed Tommy a check paying him back with interest and a personal note from Miller thanking him for his investment.

Miller was extremely lucky to be booked into the Paradise Restaurant in New York starting on June 14, 1938 for two weeks, because this gave him a powerful radio spot on the NBC Blue Network, an exposure he never got with the earlier band (who had just one gig with a very limited radio range). This led to further bookings in and around the New York-New Jersey area and, in September 1938, to his recording contract with RCA’s Bluebird label. Unfortunately, this was one time when Miller somehow made a very poor decision to write and record a two-part arrangement of Thurlow Lieurance’s By the Waters of Minnetonka, surely one of the most vapid charts he ever wrote. It was an absolute bomb, as were several of his first records. The only ones to make a splash were his sensitive arrangement of My Reverie, based on the Debussy piece, with a nice vocal by Eberle, and a fairly good arrangement of King Porter Stomp.

But the band was clearly on the way up. In December, the Paradise Restaurant brought him back, this time for an extended engagement, and in the spring of 1939 he was booked into the even more prestigious Glen Island Casino in New Rochelle, New York for the entire summer. By this time, too, he had replaced Gail Reese with teenaged-sounding Marion Hutton in order to appeal more to Middle America, expanded his brass section from six to eight musicians (four each trumpets and trombones), hired a helpmate in arranger Bill Finegan and finally gotten a superb big-band drummer, Maurice “Moe” Purtill. The latter two also came from Tommy Dorsey, who had tried both of them out but wasn’t crazy about them.

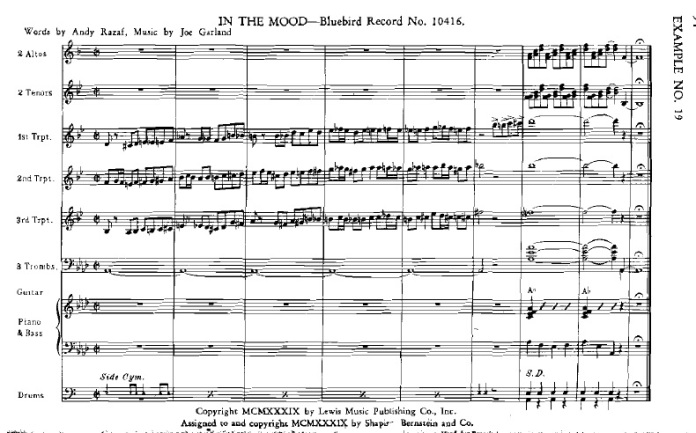

The Finegan-Miller collaboration, like Miller’s other collaborations with such gifted arrangers as Eddie Durham, Jerry Gray, Fred Norman, Billy May, Bill Challis and Mary Lou Williams, all of whom wrote for his orchestra, has always raised questions. Gray, May, Challis and Williams never said a word about how Miller adapted and rearranged their scores because the records were successful and the finished products were superb, but in later years May carped that Miller wouldn’t record half of his charts and Finegan complained that Miller stole ideas from him and didn’t always give him credit, or that he tweaked his arrangements behind his back. Well, I’m not so sure what “behind his back” meant since the band was playing them almost constantly in live performances and broadcasts, but as Bobby Hackett pointed out, Miller was indeed always tweaking arrangements his band played. Undoubtedly the most famous, but not necessarily the most artistic, of these was In the Mood. The little riff tune that we now know by that title first appeared on a Wingy Manone disc in 1930 under the title Tar Paper Stomp. Joe Garland, a black arranger, created a multi-themed version of the piece for Edgar Hayes’ band, which they recorded in February 1938. The record went nowhere, probably because there were too many themes for listeners to follow. Artie Shaw’s wildly popular 1938 swing band included a slowed-down version of  Garland’s arrangement in their broadcasts, but again the piece gained little traction and Victor wouldn’t even allow Shaw to record it. Miller, with some input from both Finegan and Durham, used just two themes, then went into a chase chorus by his two tenor saxists, Beneke and Al Klink. Afterwards he repeated the first theme, then started the slow, gradual decrescendo, extending the length of each chorus an extra two bars with pedal-point trombones, then brought it back forte with the trumpets blasting. It was ingenious; it caught dancers’ attentions; and although it didn’t sell well at first, by 1941 it was the band’s most instantly recognizable jump tune.

Garland’s arrangement in their broadcasts, but again the piece gained little traction and Victor wouldn’t even allow Shaw to record it. Miller, with some input from both Finegan and Durham, used just two themes, then went into a chase chorus by his two tenor saxists, Beneke and Al Klink. Afterwards he repeated the first theme, then started the slow, gradual decrescendo, extending the length of each chorus an extra two bars with pedal-point trombones, then brought it back forte with the trumpets blasting. It was ingenious; it caught dancers’ attentions; and although it didn’t sell well at first, by 1941 it was the band’s most instantly recognizable jump tune.

What most people don’t know, however (even Schuller was unaware of it when he wrote his book The Swing Era), is that even around the time he recorded this tightened version of In the Mood, Miller was playing the FULL arrangement, much like the Edgar Hayes recording, in his live performances and broadcasts. You can hear a rare example of this on YouTube by clicking HERE and moving the cursor to 35:03. Thus, this was a rare instance of Miller initially misjudging his own work. It was only after the record began to take off that his performances were tailored to the shorter version of the tune.

Miller also had an obvious effect on Durham’s stupendous arrangement of his own Slip Horn Jive, mostly in the irregular six-bar intro and the reed voicing that enriched the sound as well as on Finegan’s Little Brown Jug. For the latter, he helped devise and orchestrate the slow, gradual opening crescendo from just piano and drums to the full band, including one of his trademark sounds, the rapid ooh-wah sound of plunger brass. It should also be pointed out, though it is often overlooked, that Miller himself was one of his early band’s finest jazz soloists. Although he clearly did not have the smooth, rich tones of Teagarden, Dorsey or Lawrence Brown of the Duke Ellington band, he played interesting improvisations that fit the surrounding material.

And indeed, as the band grew in assurance, richness and power, this became one of its hallmarks. Miller, knowing his audiences had “slow ears,” tried to curb the more innovative solos of such players as Al Klink and, later trumpeter Billy May, who were truly original jazz men, but at the same time his fine ear for balance and structure led him to insist on, and encourage, solos that fit the surrounding ensembles and made sense within the arrangement. This is one reason why In the Mood and Little Brown Jug worked so well, and also why he was able to get so much mileage out of both fairly ordinary riff tunes like Pennsylvania 6-5000, A String of Pearls and Caribbean Clipper and such more complex charts as Johnson Rag, Anvil Chorus and Song of the Volga Boatmen, the latter written by Finegan and including a fugue in the middle.

As for May, he had a unique style of voicing and harmony that was very different from Miller, and although the leader was a bit wary about recording some of his charts he deeply respected his abilities and played them in live performances and broadcasts. Probably the most far-out May score was his late-1941 arrangement of the then-new song Blues in the Night, which turned up on LP in 1959 from a broadcast. May’s penchant for using diminished chords, atonal or modal harmonies, and voicings that gave both the brass and the saxes an edgy sound are all apparent here; from start to finish, this arrangement is a masterpiece. May also wrote a loping, medium-slow, two-beat arrangement of George Gershwin’s I Got Rhythm that sounded more like something a black band like Duke Ellington would play than Glenn Miller. Among the May charts that Miller did record were Long Tall Mama, a wonderful arrangement of Ida (Sweet as Apple Cider) featuring nice bass licks by Alpert and both a solo and vocal by Beneke, and of course Miller thought highly enough of May’s ability to ask him to come up with the minute-long bitonal introduction to Finegan’s Serenade in Blue arrangement. Yet although the Miller-May relationship was a bit strained, it was not because Glenn didn’t like his work; he just realized that it wasn’t commercial. When May tried to hand in his notice in the spring of 1942, Miller begged him to stay because he knew he was going to disband in late September to join the Army Air Force. Despite all the tensions he felt, May later said that Miller “helped me immensely. I learned a lot from Glenn. He was a good musician and an excellent arranger.”

The jazz critics of the day were quick to jump on Miller’s back for clipping his soloists’ wings and rehearsing his band like a drill sergeant, but he told them honestly, “I haven’t a great jazz band and I don’t want one. I don’t want to be the king of swing or anything else. I’d rather have a reputation as one of the best all-around bands…Our band stresses harmony. Eight brass and five reeds give you a lot of different sounds to work with…Stylization in music is inevitable. The style is the man…Would you say that Wagner wasn’t stylized? Is Ravel criticized for being Ravel?” The Miller sound, or more accurately sounds (he had about four of them), caught on so well and so quickly with the public at large that, by the end of 1939, his was the most popular big band in America, eclipsing even those of his friends Goodman and Dorsey.

Their reaction, wisely, was to regroup and re-emerge with a different sound and style. Goodman hired arrangers Eddie Sauter and Mel Powell, added Duke Ellington star Cootie Williams to his trumpet section, and ditched singer Martha Tilton, first for Helen Forrest and then for Peggy Lee. Tommy Dorsey hired a young singer who was starting to be noticed with the Harry James band, Frank Sinatra, and three arrangers to produce contrasting sounds, Axel Stordahl and Paul Weston for the medium-tempo and slow numbers featuring Sinatra and the Pied Pipers and then stealing jazz arranger Sy Oliver away from the Jimmie Lunceford band to write the jumping swing numbers.

At first, Miller resisted following Goodman and Dorsey into the field of ultra-slow romantic songs; it wasn’t really a part of him. Miller’s own recording of I’ll Never Smile Again was taken at a medium, bouncing tempo, but it utterly bombed alongside Tommy Dorsey’s slow, romantic arrangement by Sinatra, the Pied Pipers, a celesta, Dorsey’s trombone and the rhythm section. But Miller learned his lesson and, by the end of 1940, was following Dorsey into slow, lush ballads. These, too, became one of his trademarks.

By then, however, there was a serious rift between Miller and Dorsey. As soon as Miller paid off his debt to Dorsey instead of giving him a piece of his profits, the latter got mad and bankrolled a band using Glenn’s patented clarinet-led reed sound to compete with him. This band was led by a big, friendly, bear-like tenor saxist named Bob Chester, who had both talent and tons of personality. Dorsey wangled a Bluebird record contract for Chester, again to compete directly with Miller, but he should have known better. Miller, with his superior arranging skills and uncanny ability to judge the nation’s musical pulse, just kept pulling further out front. Chester did moderately well but wasn’t really stiff competition.

In the fall of 1940 he also hired Bobby Hackett as his regular rhythm guitarist and occasional trumpet soloist. Miller loved his inventive, scalar solos which fit in so perfectly with his new band concept. Hackett’s most famous recording with the band was the medium-uptempo A String of Pearls, but he made an even stronger impression on such slow numbers as Stardust, Rainbow Rhapsody, Rhapsody in Blue and the first chorus—after a startlingly inventive chromatic introduction written by Billy May—of Finegan’s arrangement of Serenade in Blue. At this time he also hired his finest bassist, Herman “Trigger” Alpert, whose superb rhythm and inventive spot solos invigorated the band, but for some reason Alpert left after only one year whereas Hackett stayed with the band until the end.

The Miller band’s two films for 20th-Century Fox, Sun Valley Serenade and Orchestra Wives, provide us with our only glimpse of the band in true stereo. The studio spared no experience in building a special soundstage for the band and insisting on Western Electric’s best sound system. The upside is that the original soundtracks, and recordings derived from it, are almost overwhelming in their impact. The downsides were that not every song they played for the films were included in them, and the tapes derived from the left-out songs are in mono (but very good, high-fidelity mono), and that not every theater that played the films had the proper sound equipment for the stereo sound to be appreciated. Because not all of the tracks existed in real stereo, none of them were issued in that format on LP or CD, but the VHS tapes and DVDs of the films include the true stereo sound. They also include some bits of the arrangements inexplicably omitted from the issued recordings, such as the full chorus of soft trombone playing in At Last.

Almost as soon as war was declared by President Roosevelt in December 1941, Miller applied for an application to the Army Air Force, but his application was ignored for months because he filled it out in his birth name, Alton. Glenn was his given middle name. Eventually the AAF realized who Alton Glenn Miller was and he was accepted. Miller broke up the civilian band in September of 1942 and immediately went to New Haven, Connecticut, where he spent a few months assembling the band he would bring overseas.

Surprisingly, only one of his civilian band members was chosen, and that was Trigger Alpert. The rest of the band consisted of musicians from other bands, among them trumpeters Bobby Nichols from the Vaughan Monroe band (he played the terrific solo on St. Louis Blues March) and Bernie Privin from Artie Shaw’s orchestra, clarinetist Michael “Peanuts” Hucko who had been with the Will Bradley-Ray McKinley band, McKinley himself on drums, and tenor saxist Vince Carbone. He also added something that Dorsey had done with his band but Miller had not with his civilian band, a full body of strings. Some listeners were disappointed by the results, particularly since Miller resorted to playing a lot of ballads, many of them in very bland, mood-music-style arrangements. But there were compensations. Ray Eberle’s somewhat tight tenor voice was replaced by the warmer, more relaxed singing of Johnny Desmond and Marion Hutton’s puerile voice was replaced by the up-and-coming Dinah Shore.

In addition, when the band did play jump tunes, some of them staples of his civilian band and some of them new to the repertoire (such as versions of Flying Home and Mission to Moscow superior to the Lionel Hampton and Benny Goodman originals and an almost surrealistic arrangement of Pistol Packin’ Mama), the band jumped even better than its civilian counterpart. Much of this was due to McKinley, whose drumming was even looser and more creative than Moe Purtill’s, but also to the gutsy, almost R&B-styled tenor solos of Carbone, Hucko’s inventive clarinet solos and the crackling trumpet playing of Nichols and Privin. Another surprise addition to the band was former Goodman pianist and arranger Mel Powell, who wrote a fascinating piece titled Pearls on Velvet that began as a mood piece but, after juxtaposing interspersed uptempo breaks with the soft string passages, suddenly broke out into a swing piece that used elements of both the string theme and the interspersed breaks to create a whole piece. Another benefit of the AAF band was that their performances were recorded in pristine high-fidelity sound by the best sound engineers in the service.

Miller’s disappearance, purportedly over the English Channel, in December 1944, has remained a great mystery, not the least of which was that the normally over-careful Miller threw caution to the winds and decided to go up anyway despite a raging thunderstorm that was sure to toss the light Norseman plane around. One of the more outlandish rumors being spread on the internet was that he was holed up in a Parisian brothel, where he got drunk and somehow met his end. This is beyond belief. Although Miller was known to be a nasty drunk, he purposely curtailed his drinking for that very reason, particularly when he was in the service, which he took very seriously. The most believable story comes from an American soldier stationed in Paris at the time, Fred Atkinson Jr., who claimed in 1999 that his buddies were sent out to investigate a plane crash, that they saw the bodies and identified them by their dogtags, and one of them was Glenn Miller. Atkinson claimed that the story was hushed up because one of the top military brass had overridden the order that the plane not take off that day due to the bad weather, and if it was investigated his name would come up and he might be court-martialed for reversing an Army decision. This would also explain why, when a British investigator tried to obtain access to the Army records pertaining to Miller’s disappearance in the 1980s, they were still sealed and would not be released.

Whatever the case, there is no question but that Glenn Miller was one of the most gifted and original arrangers of his day. In 1943, by which time he was already in the AAF, he published a book on arranging through Mutual Music because, as he put it in the preface, “Many comprehensive volumes have been written about harmony, theory, counterpoint, orchestration and composition, but to my knowledge, no book has ever been written which actually told how to make an arrangement.” As short as the book was—only 140 pages—it was quite thorough, starting out with a chart showing the possible range of each instrument in a jazz or dance orchestra, explaining that the term “possible” was given only insofar as the leader could obtain excellent performers who had that range. For the combination of clarinet and tenor saxes he warned the prospective arranger to “Avoid staccato passages as short notes do not permit sufficient duration for good blending of all voices,” while combining altos and tenors was “Suitable for legato or rhythmic melodies—background for solo instrument or solo voice—melodic line for modulations—introductions—interludes—endings—background rhythms and background sustained passages.” He then goes through a dozen different reed combinations, some including baritone saxophone, and explains the function and strengths of each of them. Similarly different voicings are explored for the trumpet and trombone sections, breaking each one down to its best-sounding combination and its suggested use. After that, he then explores more complex chord voicings using the full complement of eight brass as a unit, showing the best possible placement for each instrument within each chord; he even explains the best use of the cup or plunger mutes.

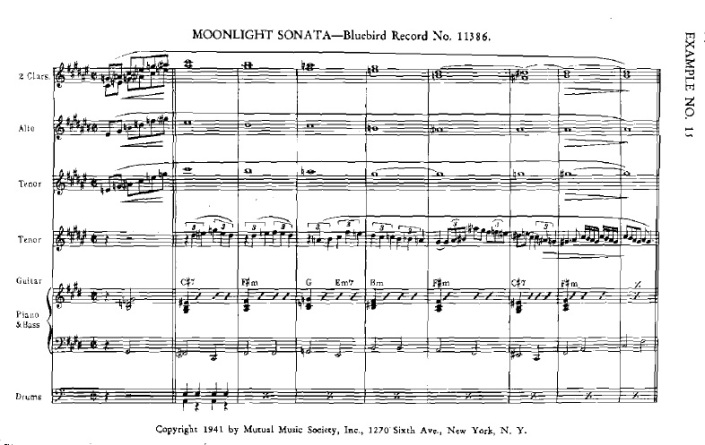

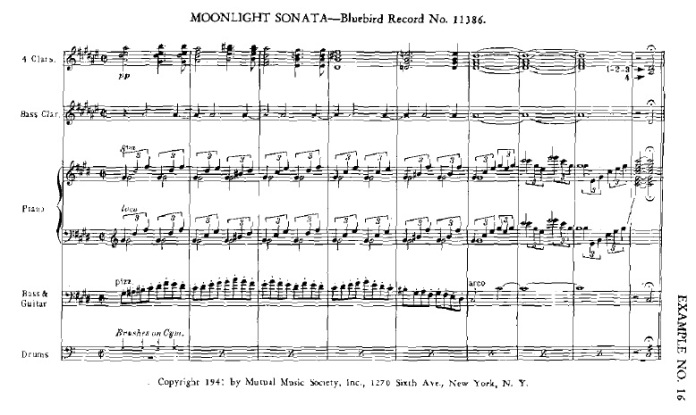

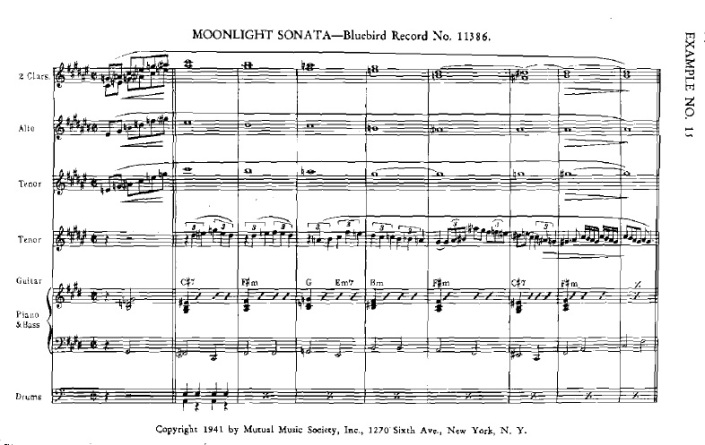

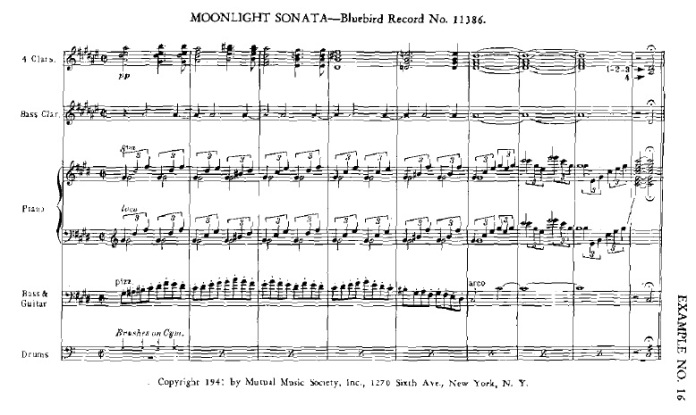

By page 52, he is exploring more sophisticated voicings for major or minor triads, 7th, 9th, 11th or 13th chords, and on p. 54 he gives you the natural harmonic series of the trombone (his own instrument) in order to explain how “the best method of doubling notes in a chord is that which conforms most closely to the natural harmonics of a ‘fixed wind column’” of that instrument. He then explains the best method of varying the rhythm section, how to intersperse ensemble or ad lib solo breaks into a drum solo, and then—finally—breaks down the creative process of creating an arrangement. For this, “If a tune has been chosen for you, but you consider it a poor tune, then accept it as a personal challenge to make a fine arrangement of it. There is no tune so bad that a wonderful arrangement won’t make it sound good.” He then shows you how to adapt, for instance, the piano part of the rather mundane Sylvia Lee song I’m Thrilled before going step-by-step through the process of creating an arrangement from introduction to final chorus, including where are the best places to insert modulations or coloristic effects. Samples of his charts of A String of Pearls and Keep ‘Em Flying are then printed out for study, along with excerpts from On the Old Assembly Line, Adios, Anvil Chorus, The Sprit is Willing, Sunrise Serenade, Tuxedo Junction and not one but two pages of score from the extraordinary Finegan-Miller arrangement of the first movement of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, which despite the “desecration” of a piece of classical music I, and many others, consider to be one of his masterpieces. The latter is given here for your edification:

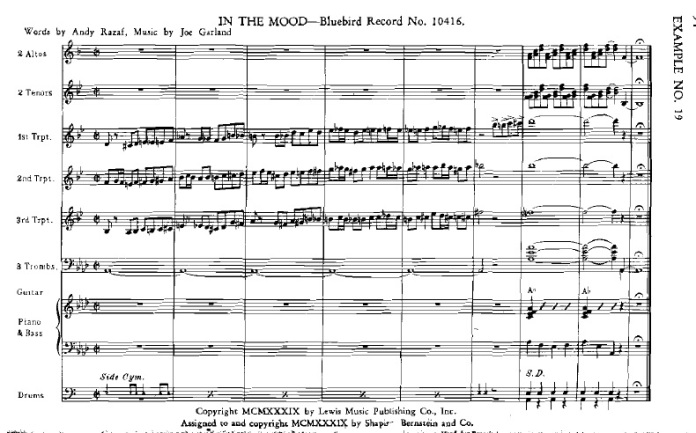

The rising chromatic brass coda to In the Mood is also included:

Unfortunately, so are a lot of ephemeral ballads, such as Yesterday’s Gardenias, Cradle Song and I’m Old-Fashioned, but c’est la vie. The book concludes with the full scores (hand-written and then photocopied) of I’m Thrilled and Song of the Volga Boatmen. Overall, this is still a valid and fairly comprehensive guide in how to arrange for a jazz-pop orchestra, and it helped a great many young arrangers who had little experience in working with this kind of an instrumental combination.

So there you have a somewhat comprehensive view of Glenn Miller’s musical mind, how it worked, and why I was so impressed as a youngster. Except for the fact that he only ventured occasionally into exotic harmonic territory, he was years ahead of virtually every other arranger of his time except for Ellington, Sauter and George Handy. Even the young Gil Evans, then working with Claude Thornhill, was only half-formed as an arranger-composer until the late 1940s. Miller was ahead of everyone else, and that is one reason why his recordings still exert an irresistible attraction even to younger listeners today.

—© 2019 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter (@artmusiclounge) or Facebook (as Monique Musique)

Return to homepage OR

Read my book, From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed guide to the intersection of classical music and jazz

WEINBERG: Symphony No. 2 for String Orchestra.* Symphony No. 21(“Kaddish”), Op. 152+ / *Kremerata Baltica; Gidon Kremer, vln; +City of Birmingham Symphony Orch.; Georgijs Osokins, pno; Kremer, vln; Mirga Gražinyté-Tyla, cond/voc / Deutsche Grammophon 483 6566

WEINBERG: Symphony No. 2 for String Orchestra.* Symphony No. 21(“Kaddish”), Op. 152+ / *Kremerata Baltica; Gidon Kremer, vln; +City of Birmingham Symphony Orch.; Georgijs Osokins, pno; Kremer, vln; Mirga Gražinyté-Tyla, cond/voc / Deutsche Grammophon 483 6566

By the time he worked with Tommy Dorsey and the Boswell Sisters in 1934, Glenn was already chief arranger and second trombone with the then-full-time Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra. Tommy especially liked Miller’s expanded-Dixieland sound, so that’s what he stuck with, writing a full-band version of King Oliver’s Dippermouth Blues, a cute original tune called Dese Dem Dose, Jelly Roll Morton’s Milenberg Joys, and a six-minute arrangement of Honeysuckle Rose. By the time the Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra broke up in 1935, Miller’s reputation as a jazz arranger had grown substantially. One story that trombonist-vocalist Jack Teagarden never tired of telling until his dying day was how Miller wrote a completely new extended introduction to Basin Street Blues for one of Jack’s Charleston Chasers sessions, the section that begins “Won’t you come along with me…Down the Mississippi…We’ll take a trip to the land of dreams…Steamin’ down the river to New Orleans.” Teagarden always felt that Miller should be listed as co-composer of Spencer Williams’ song, since everyone in the world sang or played that intro as part of the tune forever and ever, but Miller modestly waved it away as just another day’s work.

By the time he worked with Tommy Dorsey and the Boswell Sisters in 1934, Glenn was already chief arranger and second trombone with the then-full-time Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra. Tommy especially liked Miller’s expanded-Dixieland sound, so that’s what he stuck with, writing a full-band version of King Oliver’s Dippermouth Blues, a cute original tune called Dese Dem Dose, Jelly Roll Morton’s Milenberg Joys, and a six-minute arrangement of Honeysuckle Rose. By the time the Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra broke up in 1935, Miller’s reputation as a jazz arranger had grown substantially. One story that trombonist-vocalist Jack Teagarden never tired of telling until his dying day was how Miller wrote a completely new extended introduction to Basin Street Blues for one of Jack’s Charleston Chasers sessions, the section that begins “Won’t you come along with me…Down the Mississippi…We’ll take a trip to the land of dreams…Steamin’ down the river to New Orleans.” Teagarden always felt that Miller should be listed as co-composer of Spencer Williams’ song, since everyone in the world sang or played that intro as part of the tune forever and ever, but Miller modestly waved it away as just another day’s work. diversity in approach: Chinatown, My Chinatown; Dinah; and a tongue-in-cheek arrangement of Bugle Call Rag that used quotes from both a sailor song and Ravel’s Bolero. In one of his arrangements for Noble, Way Down Yonder in New Orleans, he first came up with a device that he would re-use several times with his famous civilian band: the riff that starts out softly, almost a whisper, but then gradually increases until he brings it to a roaring climax and then breaks it off to proceed to either the next theme, a variation on the theme, or (as in the case of In the Mood) a diminuendo in the coda. And when Bunny Berigan, Benny Goodman’s star jazz trumpeter, wanted to make his first band records, Miller was the one he turned to. Glenn wrote two brilliant arrangements for Berigan, Solo Hop and In a Little Spanish Town, in one night and recorded them the next day.

diversity in approach: Chinatown, My Chinatown; Dinah; and a tongue-in-cheek arrangement of Bugle Call Rag that used quotes from both a sailor song and Ravel’s Bolero. In one of his arrangements for Noble, Way Down Yonder in New Orleans, he first came up with a device that he would re-use several times with his famous civilian band: the riff that starts out softly, almost a whisper, but then gradually increases until he brings it to a roaring climax and then breaks it off to proceed to either the next theme, a variation on the theme, or (as in the case of In the Mood) a diminuendo in the coda. And when Bunny Berigan, Benny Goodman’s star jazz trumpeter, wanted to make his first band records, Miller was the one he turned to. Glenn wrote two brilliant arrangements for Berigan, Solo Hop and In a Little Spanish Town, in one night and recorded them the next day. there was a very interesting uptempo swing piece that vacillated between minor and major (the middle eight switches to major for the first four bars, then incorporates not one but two key changes in the next two bars with a return to the minor in the final two), included a vocal chorus by Lane, one by the band and a comical spoken exchange between tenor saxist Jerry Jerome and Miller, called Doin’ the Jive. I never could understand why this tune was not revived by the more famous band for Marion Hutton, Tex Beneke and Miller. It was a perfect vehicle…but perhaps he felt the minor-major switches were too complex for his listeners.

there was a very interesting uptempo swing piece that vacillated between minor and major (the middle eight switches to major for the first four bars, then incorporates not one but two key changes in the next two bars with a return to the minor in the final two), included a vocal chorus by Lane, one by the band and a comical spoken exchange between tenor saxist Jerry Jerome and Miller, called Doin’ the Jive. I never could understand why this tune was not revived by the more famous band for Marion Hutton, Tex Beneke and Miller. It was a perfect vehicle…but perhaps he felt the minor-major switches were too complex for his listeners. Garland’s arrangement in their broadcasts, but again the piece gained little traction and Victor wouldn’t even allow Shaw to record it. Miller, with some input from both Finegan and Durham, used just two themes, then went into a chase chorus by his two tenor saxists, Beneke and Al Klink. Afterwards he repeated the first theme, then started the slow, gradual decrescendo, extending the length of each chorus an extra two bars with pedal-point trombones, then brought it back forte with the trumpets blasting. It was ingenious; it caught dancers’ attentions; and although it didn’t sell well at first, by 1941 it was the band’s most instantly recognizable jump tune.

Garland’s arrangement in their broadcasts, but again the piece gained little traction and Victor wouldn’t even allow Shaw to record it. Miller, with some input from both Finegan and Durham, used just two themes, then went into a chase chorus by his two tenor saxists, Beneke and Al Klink. Afterwards he repeated the first theme, then started the slow, gradual decrescendo, extending the length of each chorus an extra two bars with pedal-point trombones, then brought it back forte with the trumpets blasting. It was ingenious; it caught dancers’ attentions; and although it didn’t sell well at first, by 1941 it was the band’s most instantly recognizable jump tune.