THE MENUHIN CENTURY: THE COMPLETE RECORDINGS WITH HEPHZIBAH MENUHIN / MOZART: Violin Sonatas: No. 35 in A, K. 526 (2 vers); No. 24 in F, K. 376; No. 18 in G, K. 301: II. Allegro; No. 26 in B-flat, K. 378: II. Andantino sostenuto e cantabile; No. 27 in G, K. 379; No. 35 in A, K. 526: III. Presto; No. 33 in E-flat, K. 481: II. Adagio. Concerto for 2 Pianos in E-flat, K. 365. 1,6,9 Piano Concertos: No. 14 in E-flat, K. 449 1,9; No. 19 in F, K. 459. 1,9 Concerto for 3 Pianos in F, K. 242 1,5,11 Piano Quartet No. 1 in G min., K. 478 3,7 / BEETHOVEN: Violin Sonatas Nos. 3, 5 (2 vers), 7, 9 (2 vers), 10 (2 vers); No. 8: III. Allegro vivace. Rondo in G, WoO 41. Trios: No. 3 in C min., Op. 1 No. 3; 4 No. 5 in D, “Ghost” (1st vers,2 2nd vers3); No. 6 in E-flat, Op. 70 No. 2; 3 No. 7 in B-flat, Op. 97, “Archduke.”3 Piano Concerto No. 3 in C min., Op. 37 1,10 / SCHUBERT: Rondo in B min., D. 895, “Rondo Brillant.” Piano Trios: No. 1 in B-flat, D. 898; 3 No. 2 in E-flat, D. 929; 3 in B-flat, D. 28; 3 in E-flat, D. 897, “Notturno”3 / BRAHMS: Violin Sonatas: No. 1 in G. Op. 78; No. 3 in D min., Op. 108 (3 vers); Sonata in A min., “F-A-E”: III. Scherzo. Horn Trio in E-flat9 / FRANCK: Violin Sonata in A, M. 8 (2 vers) / LEKEU: Violin Sonata in G / BARTÓK: Violin Sonata No. 1 / ENESCU: Violin Sonata No. 3 in A min., Op. 25 (2 vers) / PIZZETTI: Violin Sonata in A / BACH: Violin Sonata No. 3 in E, BWV 1016 / SZYMANOWSKI: Myths, Op. 30 No. 3: Dryads and Pan / SCHUMANN: Violin Sonata No. 2 in D min., Op. 121 (2 vers) / TCHAIKOVSKY: Piano Trio in A, Op. 50 (1st vers,2 2nd vers3)/ ELGAR: Violin Sonata in E min., Op. 82. VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: Violin Sonata in A min. / MENDELSSOHN: Double Concerto for Violin & Piano in D min. 1,9 / Yehudi Menuhin, violinist/1conductor; 2Maurice Eisenberg, 3Maurice Gendron, 4Pablo Casals, cellists; Hephzibah Menuhin, 5Yaltah Menuhin, 5Jeremy Menuhin, 6Fou Ts’ong, pianists; 7Luigi Alberto Bianchi, violist; 8Alan Civil, hornist; 9Bath Festival Orchestra; 10Philharmonic Orchestra de l’ORTF; 11London Philharmonic Orchestra / Warner Classics 825646208302 (20 CDs)

This is the second “monster” release by Warner Classics, new corporate conglomerate owner of what used to be EMI records, to celebrate the “Menuhin Century” of 2016. The great thing about this specific release is that it gives us all of his recordings with his younger sister, Hephzibah, on piano. The awful thing is that, unless you fork out big money for the hard copies of the CDs, you won’t have a clue what you’re getting unless you spend close to an hour, as I did, online digging up who the accompanying musicians and orchestras are, and even then you don’t have recording dates because the booklet they give you to download with this set provides no such information. The only additional info is this thing, from the Warner Classics website page:

Which is next to nothing. I was able to find the accompanying musicians and orchestras for all the other works by going to four or five different sites online (after sifting through a dozen dead ends), but alas, I cannot provide you with any recording dates except for the first Tchaikovsky Trio, recorded on March 3 & 4, 1936, and the first version of the Beethoven “Ghost” Trio, which was recorded on March 5, 1936. I only have release dates for some of the others. Not providing recording dates for everything, at the very least, is completely irresponsible in a set of this magnitude.

The other botch job on this set is the sound quality of the 78-rpm transfers (at least a third of the recordings). In some cases, not many, it sounds as if the engineer went out of his or her way to clean up as much surface noise as possible, but in those cases they left behind a fairly dull-sounding artifact that needed considerable high-end brightening to come close to simulating the sound of Menuhin’s violin tone, which was light and bright throughout his career. In most of the others, they left so much surface noise in that the recordings sound as if they come from the stone age of electrical recording, which they do not. In those cases, both noise removal and sonic brightening were needed to give some life to them.

In only one case do I forgive them for what they did, and that is on the rare performance of Szymanowski’s Dryads and Pan from his Myths. This was an unissued recording that suffered much the same bad pressing and electroplating that befell Arturo Toscanini’s Philadelphia Orchestra recordings of 1941-42. There are sections where the sound of Yehudi’s violin and Hephzibah’s piano breaks up into powder with partial interruptions and considerable surface noise. The engineer did a pretty good job of restoring this as best he or she could, and it is indeed a remarkable performance, although why on earth they didn’t re-record it remains a mystery. But the engineer botched the Brahms Sonata No. 1 the same way, allowing the “crumbling” sound of the original records to remain, particularly in quiet passages, and there are other, less obvious but no less irritating moments throughout the 78-rpm recordings (of which there are many). Some of the stereo recordings also needed some top-end brightening, too, particularly the live performance of the Mozart Piano Quartet No. 1, a splendid interpretation that sounds as if it were recorded under a blanket.

I wanted to get my carping about this set out of the way first because so much of what follows is going to be praise—not for the uneven engineering or the shoddy packaging, but for the actual performances. When I was much younger, I ran across a couple of 78-rpm sets on RCA Victor of Yehudi and Hephzibah playing together (one of them a Mozart sonata, the other Beethoven), and was absolutely thrilled. In my estimation, except for the occasional “special guest” accompanists that Yehudi had in his career, such as harpsichordist Wanda Landowska in his New York Town Hall Bach concert or his mid-‘60s CBC performances of Beethoven and Schoenberg sonatas with pianist Glenn Gould, Hephzibah was the finest accompanist he ever had.

Hephzibah Menuhin, c. 1970

The reason was not just that she was a fine pianist who could play virtually any style of classical music, though that was true. Nor was it because she never chose to have a solo career, preferring to be her brother’s “go-to” accompanist of choice for nearly a half-century. It was because she, even more so than her younger sister Yaltah—also a fine pianist—had a real psychic connection with her brother. When Yehudi and Hephzibah played together, it was the same brain playing both violin and piano. They felt the contours of the music exactly alike: not only the same tempos and phrasing, but the same approach to dynamics, attack, even the length of the occasional brief pauses between notes. “Yehepzibah” was a classical duo unlike any other in history, and it’s a perfect miracle that they recorded together so often. Listening to many of these recordings, I almost imagined that I was hearing to Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn playing together, so close was their musical affinity for each other.

Listening to the whole set is truly a heady experience, and even though I liked most of the music and certainly like the performers, it took quite a bit of patience to slog through it all. I mean…20 CDs’ worth of music? This is sensory overload of a conspicuously sadistic kind, no matter how much you may love the Menuhins, separately or together.

A personal note. When I was first getting into classical music, I heard the old 1940 recording of the Beethoven Violin Concerto by Jascha Heifetz and Arturo Toscanini. Despite the dry, boxy sound, I love the boldness of the musical conception and also could appreciate—even at a young age—Heifetz’ sturdy, piercing but generally interesting sound. A few years later, however, I heard the Menuhin-Furtwängler recording of this same concerto and was hooked. Menuhin didn’t seem to be trying to prove he was the world’s greatest violinist, which Heifetz always seemed to be doing, and I loved his more relaxed (but still vibrant) approach to the music and especially that sweet, pointed tone of his. From that day forward, he was my favorite violinist, even more so than Kreisler or Oistrakh (who I also liked quite a bit), at least until Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg and Kyun-Wha Chung came along. I was also lucky enough to hear him in person once, in the mid-1990s, near the end of his career, playing the Beethoven Concerto. He had some rough spots that night, but for the most part his tone was how I remembered it from recordings. I feel so blessed to have at least seen him, but was disappointed that he wasn’t feeling well enough to greet visitors backstage. I would have loved to have told him how much his playing had meant to me over the decades.

Hephzibah, of course, I never heard. As Yehudi put it, she clearly had the technique and style to pursue a solo career, but preferred a back seat to her brother. There is a quote from her online that “Freedom means choosing your own burden.” I suppose that being her brother’s preferred musical doppelgänger was good enough for her.

What I didn’t know was that she recorded so much with him, and so late, too, well into the 1970s. Because of my early limited exposure to just a few of her recordings with Yehudi, I came to think of their duo partnership as an intermittent thing of the 1930s and ‘40s. Clearly, as this set proves, I missed a lot of their later collaborations, including her appearance as a piano soloist with her brother conducting. To a certain extent, Hephzibah was a hothouse flower who bloomed best in the presence of her brother (though she did record the two Brahms Clarinet Sonatas with George Pieterson for Philips), but when she bloomed the blossom was fragrant, vibrantly colored and irresistable.

Yet there were misfires, as this set proves, and they weren’t always the unissued recordings. Superb in Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Franck, Enescu and Szymanowski (I’d even go so far as to say that the Menuhins’ Mozart Sonata recordings are the best I’ve ever heard), she was curiously cold in Bach, Lekeu, Pizzetti and Tchaikovsky. What makes the latter so surprising is that, especially in the earlier version of the Trio, Yehudi is his inimitable best, his violin dancing and singing alternately throughout (with Maurice Eisenberg on cello) while Hephzibah sounds oddly klunky and stiff, even playing some wrong notes (not at all typical for her). What’s particularly surprising about this is that the Beethoven “Ghost” Trio, made the very day after they finished the Tchaikovsky, is a phonographic classic, Hephzibah in particular digging into the music with drama and fire. But sometimes they both fizzled out, such as in the first recording of Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” Sonata. I think both of them decided to play it more lyrically than is usually done, and this they accomplished, but the sonata completely loses its edge. Yet ironically, their early performances of the other Beethoven sonatas have that edge and drive that the “Kreutzer” lacked. Weird, huh? Hephzibah plays far better technically in the stereo recording of the Tchaikovsky Trio with Gendron on cello. Interestingly, the performance style of this version is more French than Russian, yet it is tremendously exciting and valid.

Interestngly, some of the later mono and stereo remakes of the earlier pieces just aren’t as successful, but some of this has to do with Yehudi’s emotional response. His playing in the later version of the “Ghost” trio is very fine, and still recognizable as Menuhin, but that certain something is gone. I ascribe it in part to the change of cellist: Maurice Gendron simply isn’t as interesting as Eisenberg, and Hephzibah’s accompaniment lacks that certain something it had in 1936. Some of this also afflicts the “new” pieces, too, such as the Brahms Horn Trio. This performance doesn’t come close to the superb recording by Zbigniew Zuk, Jan Stanienda and Piotr Folkert on Zuk Records, let alone the classic 1933 account by Aubrey Brain, Adolf Busch and Rudolf Serkin for EMI. It’s a complete emotional neuter from start to finish. On the other hand, the duo’s later recording of the Beethoven Sonata No. 10 is nearly as good as their first, and the “Kreutzer” Sonata remake is better (though not on a level of the best versions, e.g. Bronislaw Huberman with Ignacy Friedman or Barbara Govatos with Marcantonio Barone). For whatever reason, neither Yehudi nor Hephzibah really “let go” emotionally in the “Kreutzer.” I have no idea why, as it suited their temperaments well (and EMI seems to think highly of this recording, reissuing it on other CDs). They’re also emotionally circumscribed in a prim performance of the “Archduke” Trio, and the stereo remake of the Enescu Sonata No. 3 completely lacks the mystery of the old mono version.

Sometimes the remakes, when not too far apart in time, are of equal quality. Such was the case with the Brahms Sonata No. 3. The second version is slightly slower than the first, not by much, yet the tensile strength of both Yehudi’s and Hephzibah’s playing remains, and the emotional involvement is similar—so much so that, except for the fact that Warner wanted to include everything, there was really no reason for the duplication. The third version, similar to the second, was simply done to have it in stereo. Better they should have remade the Szymanowski. The second version of the Beethoven Sonata No. 10 is considerably slower than the first, and emphasizes the rhythm and nuances of the music differently. I found it interesting in its own way—had I been in the concert hall, I probably would have liked it very much—but overall, I preferred the earlier version.

Maurice Gendron

Of the three cellists heard here, I prefer Casals and Eisenberg. French cellist-conductor Maurice Gendron, once a famous name, has a sound that is a bit light for my taste but plays well in context. He is best in the Brahms, Schubert No. 2 and Tchaikovsky Trios.

The stereo recording of the Beethoven “Spring” Sonata (No. 5) is lovely and charming in its own way, and without an earlier comparison one accepts it as a very fine performance, yet in the back of my mind I suspect that the lift and lilt of Yehudi’s violin would have been livelier back in the 1930s or ‘40s. It’s hard to say about the Bartók First Sonata, however; this is a performance of incredible intensity but their first recording of it, and I think the newness of the piece inspired them both. Yet the same is true of their stupendous second reading (high fidelity but not stereo) of the Schumann Sonata No. 2.

So what inferences can we draw from these performances? My own reaction is that, like so many classical musicians whose names were not Arturo Toscanini or Annie Fischer, Yehudi Menuhin was better in certain pieces the first several times he played them. As time went on, his repertoire grew and new interests replaced the old, his performances remained highly professional and still had his stamp on them, but were less imaginative. The same thing was true of his various recordings of the Beethoven Violin Concerto. The very first one with Wilhelm Furtwängler from the late 1940s was the most fascinating. The second version with Furtwängler, the famous 1953 studio recording, was still very fine and had similarities to the first, but lacked some of its spontaneity. The third version with Constantin Silvestri was also a shade less lively, but still recognizably Menuhin, while his last version, with Otto Klemperer, was stodgy, not just because late Klemperer was stodgy (which he was) but because Menuhin had probably had enough of the Beethoven concerto by then. (He was also somewhat uninvolved when I heard him in the 1990s, but I put that down to old age.) Interestingly, I always felt that his amanuensis, Heifetz, managed to retain an interest in every piece he ever played. Some later Heifetz performances were slightly less interesting than his earlier versions, but just slightly.

And of course, as Yehudi’s moods went, so did Hephzibah’s. She mirrored them perfectly, and did so for a very long time, but it was always his moods. She was her brother’s favorite passenger on his journey through music, but never the driver of the car. Perhaps this was what she meant when she said “Freedom is choosing your own burden.” It should be noted, however, that Yehudi constantly urged her to pursue a solo career, so I’m not blaming him for her decision to stay his accompanist. And, as I’ve mentioned, he usually played better with her than with anyone else in chamber music. Their performances of the Elgar and Vaughan Williams Sonatas are simply terrific: impassioned and full of fire, the way they should have played the”Kreutzer.”

It’s interesting to hear the concerto recordings with Yehudi conducting and Hephzibah as soloist. For all his allegiance to Furtwängler, Menuhin’s conducting style was rooted in that of Szell or Toscanini: direct, unfussy, dramatic and binding the music in such a way as to emphasize its structure. One expects Hephzibah to be at her best in the Mozart Concertos, and she is (particularly reveling the lesser-known 2- and 3-piano concerti), but more surprising is her performance of the Beethoven Third. Not quite as forceful as Fleisher (with Szell), Serkin or Arthur Rubinstein, she nonetheless surprises one with her complete grasp of a piece she probably never played in public before or after. She exhibits a tensile strength and intuitive sense of drama, helped tremendously by ber brother’s splendid conducting. This is yet another instance of the symbiotic relationship that existed between them, and as the performance evolves one can clearly hear Yehudi whipping up the orchestra in certain sections to match his sister’s impassioned attacks. Once again: two minds operating musically as one. It could just as well have been both played and conducted by Hephzibah.

There is, of course, much I could say of every performance in this set, but for the most part I think that pretty much wraps things up. You may have your own favorite recordings as you go through the set, and your taste may certainly differ from mine, but I am giving you the benefit of my own reaction based on decades of listening. If you choose to buy the set as downloads rather than hard discs, I seriously suggest that you follow at least some of my recommendations to save yourself some money. Their collaboration was a valuable and unique one, but not as consistent as the publicity blurbs want you to believe.

—© 2017 Lynn René Bayley

Return to homepage OR

Read The Penguin’s Girlfriend’s Guide to Classical Music

By the early 1970s, Mayer was becoming famous for writing Indo-Jazz fusion music, thus in 1976 Lansdowne Records, a division of EMI, commissioned him to write a piece which he was to record with musicians of his own choosing. The result was Dhammapada, an eight-part suite that combined his three great loves in life: Indian music, classical music and jazz. As you can hear on this excellent reissue, the music was like nothing else then or now. It starts out gently, as music for meditation, but gradually turns into an Indian-flavored jazz romp not too far removed from the kind of music that Don Ellis had produced with the Hindustani Jazz Sextet or his own big band (although there are listeners who dislike the music of the Ellis big band).

By the early 1970s, Mayer was becoming famous for writing Indo-Jazz fusion music, thus in 1976 Lansdowne Records, a division of EMI, commissioned him to write a piece which he was to record with musicians of his own choosing. The result was Dhammapada, an eight-part suite that combined his three great loves in life: Indian music, classical music and jazz. As you can hear on this excellent reissue, the music was like nothing else then or now. It starts out gently, as music for meditation, but gradually turns into an Indian-flavored jazz romp not too far removed from the kind of music that Don Ellis had produced with the Hindustani Jazz Sextet or his own big band (although there are listeners who dislike the music of the Ellis big band).

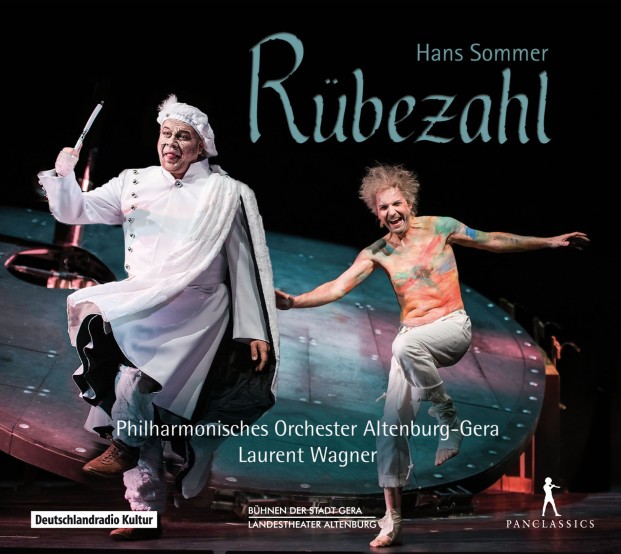

Sommer wrote a great deal of lieder when he was younger which is also rather forgotten today, yet one of his lieder collections led to his meeting Richard and Cosima Wagner in 1875. The Wagners were much taken with the young man and recommended him to Cosima’s father, Franz Liszt, for further study. In the 1890s he began writing operas, of which the first was Lorelei in 1891. The current work, Rübezahl und der Sackpfeifer von Neiße (to give it its full title) was premiered under Richard Strauss’ baton in 1904. So why isn’t he or this opera better known? For one thing, Sommer conspicuously avoided a publisher for his music. For whatever reason—caprice, paranoia or just laziness—he never bothered to get any of his works published. He also wasn’t particularly energetic about self-promotion, and without an agent no one else was going to stump for him either. Thus he just sort of faded into oblivion as time went on.

Sommer wrote a great deal of lieder when he was younger which is also rather forgotten today, yet one of his lieder collections led to his meeting Richard and Cosima Wagner in 1875. The Wagners were much taken with the young man and recommended him to Cosima’s father, Franz Liszt, for further study. In the 1890s he began writing operas, of which the first was Lorelei in 1891. The current work, Rübezahl und der Sackpfeifer von Neiße (to give it its full title) was premiered under Richard Strauss’ baton in 1904. So why isn’t he or this opera better known? For one thing, Sommer conspicuously avoided a publisher for his music. For whatever reason—caprice, paranoia or just laziness—he never bothered to get any of his works published. He also wasn’t particularly energetic about self-promotion, and without an agent no one else was going to stump for him either. Thus he just sort of faded into oblivion as time went on. In the third act, Buko swears revenge on those who attempt to topple him, but Gertrud, the only person who means anything to him, has suddenly come down with a horrible fever. Her maid, Brigitte, tells Buko that Gertrud talks in her fevered sleep about a man she loves. Buko orders a servant to summon Zagel to play the pipes for him, but unbeknownst to him the real Zagel refuses to appear and it is Rübezahl in disguise (once again) who takes his place. Rübezahl reveals his true identity, urging Buko to let Wido and Gertrud marry, but the enraged despot has the mountain spirit thrown into prison. Gertrud, somewhat recovered, confronts her father and admits her love for Wido, which ends with her father banishing her. A servant rushes in to report that the real Ruprecht Zagel has died.

In the third act, Buko swears revenge on those who attempt to topple him, but Gertrud, the only person who means anything to him, has suddenly come down with a horrible fever. Her maid, Brigitte, tells Buko that Gertrud talks in her fevered sleep about a man she loves. Buko orders a servant to summon Zagel to play the pipes for him, but unbeknownst to him the real Zagel refuses to appear and it is Rübezahl in disguise (once again) who takes his place. Rübezahl reveals his true identity, urging Buko to let Wido and Gertrud marry, but the enraged despot has the mountain spirit thrown into prison. Gertrud, somewhat recovered, confronts her father and admits her love for Wido, which ends with her father banishing her. A servant rushes in to report that the real Ruprecht Zagel has died. In the fourth and last act, Buko visits Zagel’s grave, the gravedigger explaining that sometimes Wido comes there to pray. When Wido arrives, he is arrested by guards and taken before Buko. Gertrud pleads for her lover, but is also arrested. Wido then summons Rübezahl, who arises from the grave along with all the dead spirits, who come to life and demand justice from Buko. When the clock strikes the hour, the tower collapses, Buko dies, and the wise man Theobald Kraft becomes the new ruler. Everyone still surviving then lives happily ever after, The End.

In the fourth and last act, Buko visits Zagel’s grave, the gravedigger explaining that sometimes Wido comes there to pray. When Wido arrives, he is arrested by guards and taken before Buko. Gertrud pleads for her lover, but is also arrested. Wido then summons Rübezahl, who arises from the grave along with all the dead spirits, who come to life and demand justice from Buko. When the clock strikes the hour, the tower collapses, Buko dies, and the wise man Theobald Kraft becomes the new ruler. Everyone still surviving then lives happily ever after, The End.