MYRIAD3 MOONS / DONNELLY: Skeleton Key; Unnamed Cells; Sketch 8. CERVINI: Noyammas; Ameliasburg; Moons; Brother Dom. FORTIN: Stoner; Peak Fall; Exhausted Clock. DISASTERPEACE: Counter of the Cumulus / Myriad3: Chris Donnelly, pn/synth; Don Fortin, bass/fretless bs/synth; Ernesto Cervini, dm/glockenspiel / Alma ACD52062

On the surface Myriad3 is another jazz piano trio, but one doesn’t have to listen very long to realize that there is much under the surface and it’s pretty eclectic and interesting. This despite the fact that there are elements of minimalism (Skeleton Key) and ambient jazz (Stoner) mixed in with their strong jazz roots. I was not particularly pleased by their use of a rock beat on the opening track, but as the late tenor Peter Pears said in 1975 about radio, rock music seems to be “the coming thing.” The nice aspect of Myriad3’s performance, however, is that it has a nice, gentle swing to it, one might almost say an updated version of Vince Guaraldi’s sound from the ‘60s.

I also found it refreshing that all three of the trio’s members, including drummer Ernesto Cervini, contribute charts to this collection, and each of them have a different perspective. This is evident in the second track, Ernesto Cervini’s Noyammas, with its slyly morphing beat and semi-fluid chord structure. As I’ve mentioned about some other modern bands, Myriad3 also seems to take a cue from the compositional style of Charles Mingus, for whom such fluid structures were normal. Unnamed Cells, like Skeleton Key, has elements of minimalism, for instance, but the beat is not only not in a rock mode but also asymmetrical in feeling, at leas until the fretless electric bass comes in and we return to a steadier pulse. I noticed as I was listening that Myriad3’s improvisations are all based on the underlying pulse more so than even the chord structure, certainly an unusual approach to music. In this respect, their scores have a certain kinship with Beethoven, for whom rhythm was the root of everything. This emphasis on the rhythmic angle allows the group to cohere more frequently than many other bands, large and small, that use irregular or asymmetric rhythms, because those bands keep shifting the beat as the soloists improvise. Myriad3’s players, on the other hand, only shift the beat when the next section of the tune arrives or when the improvisation demands an altered tempo.

Stoner by bassist Don Fortin sounds the most conventionally relaxed, like nice, polite ambient jazz, but this perception changes subtly at the halfway mark as the music becomes more strong in its pulse and the piano’s bass line “moves” the music into somewhat different realms—all without bringing up the tempo to heighten tension—before completely relaxing at the 4:18 mark and ending in a series of long single notes. Peak Fall has a quietly meditative sound to it, as if one were sitting in a park near sunset admiring the setting sunlight reflect off gently swirling leaves of gold and brown. The allusion to “swirling” is doubly apropos here, as the beat itself begins to swirl and turn in on itself as the piece progresses. I have to compliment the sound engineer, John “Beetle” Bailey, for capturing the sound of the trio in the warmest space possible without using overdone ambience to ruin the immediacy of their sound.

Counter of the Cumulus, the only piece on here not written by a group member, was composed by electronic artist Disasterpeace. I found it too rock-like and intrusive for my taste. Happily, the group returns to its normal mein in Cervini’s jazz waltz Ameliasburg, and Donnelly’s Sketch 8 revisits the minimalist feel. Surprisingly Moons, the title track of this CD, almost has the feel of a classical prelude, being quite slow and deliberate, relying for once on the piano chords to move the music forward with no improvisation—a cloud floating across the horizon with just a bit of electronic reverb (and a bass line) towards the end. Brother Dom, with its quirky yet steady beat and simplistic melodic cells, bears a certain resemblance to the work of Carla Bley (particularly those quirky meter shifts around the two-minute mark), although here Donnelly’s piano solo put me in mind of Bill Evans from his modal period. The music becomes increasingly busier and louder as the piece progresses, and ironically the beat is shortened by fractions as the piano playing turns almost frenetic.

The album ends with Fortin’s Exhausted Clock, which starts out with a ticking sound that relaxes, then becomes irregular, and then just poops out. Donnelly contributes light right-hand sprinkles on the keyboard before the bass comes in at the one-minute mark, almost as elongated and fatigued as those clock ticks. For those of you who remember the old New York-area Late Show with its use of Leroy Anderson’s The Syncopated Clock as a theme song, this one is kind of like The Late Show on Valium. It’s also one of the few pieces on this album in which the drums become extremely busy, albeit at a soft volume (mostly snares with brushes, I think) as te piano and bass meander along.

All in all, Moons is a different kind of jazz album, showing creativity in ways that are unusual and reaching for mood and feeling as much as substance. I think you’ll like it.

— © 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Readmy book: From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed guide to the intersection of classical music and jazz

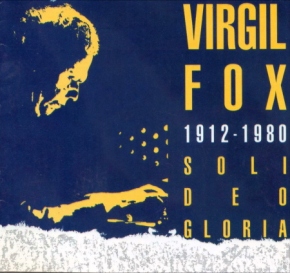

Always a pioneer in recording technology, Fox was tremendously proud of his Heavy Organ at Carnegie Hall album because he felt it captured the tone colors and registrations of his organ with perfect fidelity. He also made the first digital recordings in the United States, issued on two LPs (and later one CD) by Bainbridge Records as The Digital Fox.

Always a pioneer in recording technology, Fox was tremendously proud of his Heavy Organ at Carnegie Hall album because he felt it captured the tone colors and registrations of his organ with perfect fidelity. He also made the first digital recordings in the United States, issued on two LPs (and later one CD) by Bainbridge Records as The Digital Fox. had the cancer not affected his fingernails, which became cracked and brittle, making performing painful and difficult. One of his last concerts was the one he gave at Riverside Church on May 6, 1979, which was fortunately recorded and issued on CDs as Soli Deo Gloria. You can hear the entire concert/recording

had the cancer not affected his fingernails, which became cracked and brittle, making performing painful and difficult. One of his last concerts was the one he gave at Riverside Church on May 6, 1979, which was fortunately recorded and issued on CDs as Soli Deo Gloria. You can hear the entire concert/recording

SSM1013) not so much boring or ugly (though you are welcome to find it that yourself) so much as simply pretentious drivel. Thus I have chosen to discuss him by the name “Doodly-oo,” because his music just doodles along. In fact, considering the length of some of these works, I would go so far as to call him “Doodly-oodly-oo.” (Yes, I know the correct pronunciation of his last name is “Doo-ti-low,” but “Doodly-oo” fits his music much better.)

SSM1013) not so much boring or ugly (though you are welcome to find it that yourself) so much as simply pretentious drivel. Thus I have chosen to discuss him by the name “Doodly-oo,” because his music just doodles along. In fact, considering the length of some of these works, I would go so far as to call him “Doodly-oodly-oo.” (Yes, I know the correct pronunciation of his last name is “Doo-ti-low,” but “Doodly-oo” fits his music much better.)

Parsons, The Crystals, The Ronettes, every Phil Spector and Beach Boys record, Delaney Bramlett, Ringo Starr, Doris Day, Elton John, Ray Charles, Eric Clapton, the Byrds (Mr. Tambourine Man), Barbra Streisand, the Ventures (Walk Don’t Run), Willie Nelson, Badfinger, Harry Nilsson, Frank Sinatra (Strangers in the Night), the Band, Bob Dylan, J.J. Cale, B.B. King, Dave Mason, Glen Campbell, Joe Cocker, Freddie King and the Rolling Stones. He can still be seen on YouTube in early clips from the T.A.M.I Show, playing and singing Roll Over Beethoven, and 1965’s Shindig performing Jambalaya with a young Glen Campbell on banjo.

Parsons, The Crystals, The Ronettes, every Phil Spector and Beach Boys record, Delaney Bramlett, Ringo Starr, Doris Day, Elton John, Ray Charles, Eric Clapton, the Byrds (Mr. Tambourine Man), Barbra Streisand, the Ventures (Walk Don’t Run), Willie Nelson, Badfinger, Harry Nilsson, Frank Sinatra (Strangers in the Night), the Band, Bob Dylan, J.J. Cale, B.B. King, Dave Mason, Glen Campbell, Joe Cocker, Freddie King and the Rolling Stones. He can still be seen on YouTube in early clips from the T.A.M.I Show, playing and singing Roll Over Beethoven, and 1965’s Shindig performing Jambalaya with a young Glen Campbell on banjo. distributed by Capitol-EMI. There are two ironies about that first album. One was the adoption of an inverted “Superman” S on an eggshell as their logo, which they were eventually sued for by DC Comics, and the other was his setting of Bob Dylan’s song Masters of War to the melody of The Star-Spangled Banner. The latter became so offensive to many people that after the first pressing, Shelter was persuaded to simply omit the track from all subsequent pressings on LP.

distributed by Capitol-EMI. There are two ironies about that first album. One was the adoption of an inverted “Superman” S on an eggshell as their logo, which they were eventually sued for by DC Comics, and the other was his setting of Bob Dylan’s song Masters of War to the melody of The Star-Spangled Banner. The latter became so offensive to many people that after the first pressing, Shelter was persuaded to simply omit the track from all subsequent pressings on LP.