GUILLOU: Fantaisie Concertante.2 Toccata. Ballade. Hyperion ou la rethorique du feu. Peace.3 La chapelle des abimes. Aube.3 Symphonie Initiaque. Andromeda.9 Suite pour Rameau. Éloge. Säya ou l’Oiseau Bleu. Sinfonietta. Colloques Nos. 54 & 44,5. Fête.6 Fantaisie. Intermezzo.7 Scènes d’Enfants. Sagas Nos. 1-6. 18 Variations. Alice au pays de l’orgue.8 Jeux d’Orgue. Saga No. 7. Ballade No. 2, “Les chants de Selma.” MUSSORGSKY: Pictures at an Exhibition (arr. Guillou). RACHMANINOV: Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (arr. Guillou)1 / Jean Guillou, 1Hanka Yekimova, 7Livia Mazzanti, org; 2Alexander Kniazev, cel; 3Groupe Vocal de France; 4Philippe Gueit, pno; 5Daniel Ciampolini, Vincent Bauer, perc; 6Daniel Gilbert, cl; 7Andrea Montefoschi, fl; 8François Castang, narr; 9Kiyoko Okada, sop / Universal Music Classics 00028948037247 (available at GoBuz: https://www.qobuz.com/gb-en/interpreter/jean-guillou/download-streaming-albums)

Jean Victor Arthur Guillou, who died January 26, 2019 at the age of 88, was one of the greatest organists of all time, yet he came to recording rather late in life. Before then, however, he was practically a legend in France as organist, sometimes pianist, composer, pedagogue and organ builder. Among his many talents was the ability to improvise, which was and still is a lost art for the majority of classical organists (and pianists).

When I reviewed his boxed set of Bach’s organ works several years ago for a major music magazine, I raved about his performances, noting not only the incredible energy he displayed even as an old man but also his phrasing, ability to color phrases, and yes, occasionally improvise even within a piece by Bach. I was ripped to shreds by my “fellow critics” and readers of the magazine. How DARE I praise an organist who 1) was not playing Bach on an “authentic” organ from the 18th century, and 2) had the audacity to occasionally improvise? But, as usual, they were wrong in their thinking. J.S. Bach himself was a noted improviser on the organ, particularly in his own works. As for the wheezy little instrument he had to play on in Leipzig, he hated it. Bach delighted in making “organ tours” of other churches and cathedrals, and was especially happy when he ran across organs that were not only larger but more modern and had more colors and stops. (One of his favorites was the bell or carillon stop in one organ he played. He couldn’t get enough of it.)

This 7-CD set of Guillou playing a large number of his own works dates from 2015, but seems to be a curious release. No one online has reviewed it, and I’ve only found one outlet that is actually selling it, but am here to tell you that this music is absolutely fabulous: imaginative and inventive, using modern harmonies and the full range of color available to him on his own organ built to his specifications. In the first piece, Fantaisie Concertante, he is joined by Russian cellist Alexander Kniazev, and in some others by the Groupe Vocal de France directed by John Poole. Other instrumentalists also make their appearance in this set, such as pianist Philippe Gueit in Colloque No. 5, Gueit and two percussionists in Colloque No. 6, clarinetist Daniel Gilbert in Fête and both flautist Andrea Montefoschi and second organist Livia Mazzanti in Intermezzo.

Trying to describe Guillou’s compositions from a technical standpoint is a bit tricky and difficult. Although he uses a strict musical form, his melodic lines are slithery, often predicated by the constantly shifting harmony underneath. This harmonic movement is both horizontal and vertical; those readers who have a grasp of George Russell’s Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization will know exactly what I mean. As Nadia Boulanger once said, she heard “all of music” in her head, and to an extent that was how Guillou’s mind worked. In fact, considering the brilliant—and I do mean brilliant—lines and structures of his compositions (had he written for a full orchestra he could not have done better or been more complex), it’s almost a wonder that he could focus in on the structures of Bach.

Yet, and this is the peculiar part of it, there is a connection between the two. The only big difference is that Bach wrote mostly within conventional harmony, the “well-tempered” system of the claviers and organs of his day, whereas Guillou has taken than form and blown it wide open. Ah, but you should also recall that Bach’s second-oldest son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, did the same thing, Trained by his father to hear “everything” within music, C.P.E. Bach blew the harmonic system of his time open to remarkable harmonic structures that his father dared not experiment in if he wanted to keep his job as the Thomaskantor of Leipzig—yet he did indeed indulge in some strange harmonies in his Art of Fugue. Also please remember, strange as it may sound, that Arnold Schoenberg also came out of Bach. The differences lie in these different composers’ temperaments. C.P.E. Bach, once he left Berlin for Hamburg, turned his musical imagination loose on a large and sometimes bewildering array of keyboard solos, symphonies and concerti, influencing both Beethoven and Gluck with his highly imaginative use of harmony and unusual orchestral timbres. Guillou, being a Frenchman of the 20th century, was absolutely prodigious in his assimilation of music of all streams, particularly, it seems to me, modern French music with and without the influence of Stravinsky.

Without a booklet, I don’t know when each of these works was written, but they sound so much all of a piece stylistically that it almost doesn’t matter. Although he occasionally uses the pedals, his music is generally not bass-heavy, and often he juxtaposed themes as well as timbral colors the way a master orchestrator would. There is only a slight resemblance in his music to that of another famous organist-composer of his time, Olivier Messiaen, and this is to the good. Whereas Messiaen’s often thick bitonal and atonal chords, overlaid on one another, created a sinister feeling (I’d almost call it a creepy feeling) in his organ works, Guillou’s aesthetic is tied more to the work of such predecessors as Louis Vierne and Charles-Marie Widor. The Widor influence is especially notable in a work such as the Ballade No. 1, where Guillou opens all the stops to create an almost surround-sound musical world, and he was indeed fortunate to have lived at the time of digital recording. Poor Widor only made six sides in 1932; at least they were electrical, but clearly not even close to the high-fidelity era.

I reviewed the first two CDs of this set through headphones because the other resident of my home was sleeping and I didn’t want to disturb her, and I’m glad I did. As much as you will hear through a really good home audio system, you hear even more through the headphones. Both will make you feel as if you are present at a Guillou recital, but through headphones you almost seem to be sitting in the front row, hearing a master musician at work. In a multi-movement, multi-layered piece such as Hyperion, ou La rethorique du feu, Guillou envelops the listener in an extremely complex web of rapid figures played in contrasting rhythms and a method of bitonality that keeps you in flux from start to finish, yet you never lose track of what he is doing or where the music is going. Indeed, his music is so brilliant as well as complex that it will take you a few listening to catch all of the things that are going on, except in the slowest movements where he relaxes his pace enough to focus on just three things at a time instead of five or six. I almost imagined that his musical mind must never have shut down, not even when he was asleep. Someone on this high of a genius level must have been hell to live with.

And yet, no matter how complex his music becomes, the amazing thing is that you can follow everything. This is partly due to the fact that his compositions keep everything clear whereas Messiaen often congested them with thick and undecipherable chords. That is the main reason why I prefer Messiaen’s piano and orchestral works; in those, even the densest music is made clear, in the case of the former due to the nature of the piano and in the case of the latter due to the timbral differences of orchestral sections. But it is also due to the fact that Guillou wanted all of his lines to stand out, thus he generally used very bright timbres had had an unusually crisp attack on the organ—not dissimilar from, believe it or not, the way Fats Waller played the pipe organ. The least bit of smearing or sluggishness in his fingering and some of the detail would have been lost, but Guillou had fingers of steel and extraordinary coordination of both hands.

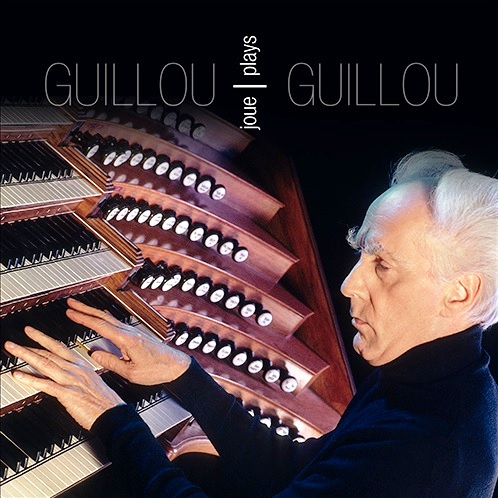

Guillou in action

In the choral-organ works, he took a page from Lili Boulanger in his writing for chorus, sometimes using contrapuntal vocal effects to (again) keep the lines clear. He also used his organ as an accompanist to the vocal lines, simplifying his approach so as not to clutter it up too much. Andromeda is a perfect example of his modus operandi: after a very fast and busy opening section, he slows things down to allow the solo soprano to sing her strophic lines (mostly within a one-octave span, though later with extensive leaps upward and downward), saving his busiest and loudest passages for the interludes. The text is based on a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins, another poem of whose was also used for Peace:

NOW Time’s Andromeda on this rock rude,

With not her either beauty’s equal or

Her injury’s, looks off by both horns of shore,

Her flower, her piece of being, doomed dragon’s food.

Time past she has been attempted and pursued

By many blows and banes; but now hears roar

A wilder beast from West than all were, more

Rife in her wrongs, more lawless, and more lewd.

Her Perseus linger and leave her to her extremes?—

Pillowy air he treads a time and hangs

His thoughts on her, forsaken that she seems,

All while her patience, morselled into pangs,

Mounts; then to alight disarming, no one dreams,

With Gorgon’s gear and barebill, thongs and fangs.

Guillou’s Suite pour Rameau sounds nothing like Rameau at all except for one section, yet for the most part this music is somewhat subdued for him, not as wild or energetic as usual. The same can also be said of Éloge or Praise which is a really strange piece, more questioning without getting any answers, with a sudden swell of volume and increase of tempo at the four-minute mark, receding again about a half-minute later. Yet the music builds to a longer crescendo between the eight and nine-minute mark, after which the music becomes much more hectic, with Guillou scrambling to get all the notes in on his multiple keyboards (and pedals).

One of the more fascinating mind-games one can play with this set is to wonder, considering Guillou’s high reputation as an improviser, how much of this music is written and how much is “off the cuff.” I would think that all of the pieces including other instrumentalists or voices are fully composed, but in the solo works there may very well be passages—several of them, in fact—where Guillou was playing in an extemporé fashion. Since my access to this album did not include the booklet, I can’t say with certainty, but I’d be very surprised if all of it were written out in advance of performance.

The two pieces titled Colloque are piano-organ duets, with No. 4 also including a pair of percussionists. No. 5, which is performed first on the CD, almost sounds like minimalism in the beginning, though the music quickly begins to develop and one realizes that it’s just a very pointillistic piece. The tempo increases, first in the piano part and then in the organ, then falls back to the initial slow tempo. Part of the music sounds 12-tone but not serial, but it soon settles into Guillou’s more familiar bitonal sound world. Later on in the piece, things become faster and much more complex, yet once again Guillou’s crisp attack and phenomenal agility keeps the lines from becoming muddy or unclear even at blistering speeds. In Fête, Guillou decided to include a clarinet, certainly one of the least likely instruments to play with an organ. The music is more “serrated” than usual for him, emphasizing that instrument’s ability to play fast passages that jump around rather than following a linear melodic pattern. The organ plays a curiously syncopated passage around the 5:48 mark that has a certain resemblance to jazz, something quite unusual for Guillou, and this feeling continues into the ensuing organ-clarinet duet passage. And, as noted earlier, Intermezzo features both a flautist and a second organist.

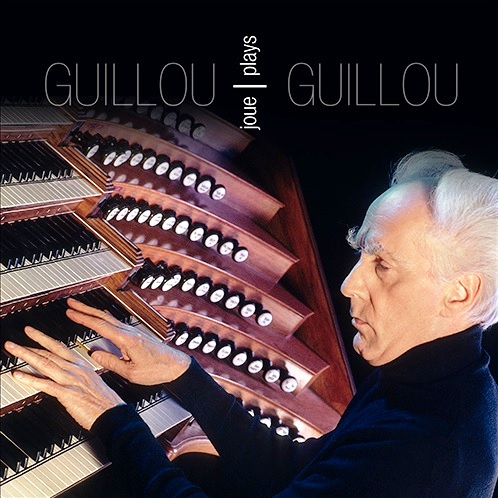

Young Jean Guillou, c. 1962

Although Guillou definitely had certain patterns that were used in many of his pieces, he varied them enough rhythmically, harmonically and especially melodically to create the feeling of having a varied compositional style. This is not easy to do, particularly when you’re working in an atonal or bitonal idiom; it’s always easier to play “follow-the-leader” rather than create your own style. It is to Guillou’s great credit that despite the huge number of works presented here, he managed to keep his powers of invention up. It would have been so easy for a composer of his genius—and I most definitely consider him a genius—to just cookie-cutter his music the way Mozart and Donizetti did. Colloque No. 4, the one with piano and two percussionists, often has a feel similar to George Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique, yet even here he pulls back from the moto perpetuo feeling to present some slow, moody passages in a stark contrast. And note that among the percussion instruments is a vibraphone, normally considered a jazz instrument, yet used here in a purely classical manner. Indeed, as the music evolves it becomes progressively quieter rather than louder, creating an otherworldly ambience that envelops the listener—at least up until about 13:12 into the piece, when a riot of timpani and snare drums reawakens the explosive energy of the opening passages.

Scenes d’enfants is a particularly wild ride on the organ, quickly assuming a rapid pace after the somewhat slow introduction. Guillou’s crisp attack is especially noticeable here as he scurries across his multiple keyboards, creating a virtual whirlwind of sound in the opening minutes. Yet, as the music develops, other themes and moods enter the picture, creating a soundscape of alternately lyrical and serrated themes, sometimes surging forward with the pedals and sometimes hanging back with bizarre floated chords. Saga No. 2 surges from the very start like an oncoming tornado or a runaway freight train, then eases up at 1:44 so that Guillou can ruminate on the organ using circular figures—yet another aspect of his various styles—before resuming freight train mode at about 2:40. The opening of Saga No. 3 sounds almost, but not quite, like Stravinsky’s Firebird.

Of his extended organ theater-piece-with-narration, Alice au pays de l’orgue, Guillou wrote:

“Ever since my earliest encounters with the organ, I have always considered the organ stops—that is, various different registers of the instrument—as resembling a collection of living beings, their character corresponding less with the form of the sound they produce. Certainly the very shape of some pipes is such that it can give rise to what is almost a psychoanalytical interpretation; thus the idea occurred to me quite naturally of bringing these different stops to life in a kind of musical story, with an accompanying narrative to introduce them and their individual sounds as sentient beings endowed with the power of movement. Lewis Carroll and his heroine Alice offered an ideal framework for a dramatization of my musical idea. Thus I imagined Alice retracing the steps which took her through the looking-glass and, this time, stepping into world quite different from that of the chessboard, a world with no Queen, no Tweedledee, no Humpty Dumpty, but with organ stops brought to life as animated flowers, with dancing Flutes, oboes, chattering Bourdons, pedantic Bombardes, biting Cromornes, rugged Clarinettes or harsh, snake-like Ranquettes. This entire universe sets itself in motion and gradually takes shape, suggesting snippets of dances or conversations in such a way that a sort of symphonic poem is built up, featuring contrasting or challenging sequences in which certain figures and themes recur with, after a strange moment of calm, ends in a wild outburst with all the stops combining in a feverish and dazzling frenzy. Alice in Organ Land may equally well be performed without the Narrator, by giving the audience the text to read, or, again, by playing just the two Waltzes together with Tarantella, or even the Tarantella alone. In this case, the pauses marked become simply a bar’s rest, without a longer pause.”

Whatever this guy was on, I want some, and I want it NOW!

Indeed, Guillou’s music is so dense and challenging that I strongly recommend that you not listen to more than two CDs complete and in order at a time. Like the music of J.S. Bach and Art Tatum, its complexity and density will overtax your mind if you indulge in too much at one sitting.

As for his organ transcription of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, I honestly didn’t like it. For whatever reason, Guillou chose lower ranges for several pieces, such as Gnomus, that didn’t work because the sound was too muddy. Since I really enjoyed his organ transcription of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, this was a major shock and disappointment for me. For even more of his genius, I recommend the fascinating album of his improvisations on Doian Sono Luminus DOR-90101 as a substitute for disc 7 of this set.

Despite the more conventional works by Mussorgsky and Rachmaninov, this is clearly not your father’s or your grandfather’s classical organ record set. Highly recommended.

—© 2019 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter (@Artmusiclounge) or Facebook (as Monique Musique)

Return to homepage OR

Read The Penguin’s Girlfriend’s Guide to Classical Music

ELFMAN: Violin Concerto, “Eleven Eleven” / Sandy Cameron, vln; Royal Scottish National Orch.; John Mauceri, cond / Piano Quartet / Philharmonic Piano Quartet Berlin: Daniel Stabrawa, vln; Matthew Hunter, vla; Knut Weber, cello; Markus Groh, pno / Sony Classical 19075869752

ELFMAN: Violin Concerto, “Eleven Eleven” / Sandy Cameron, vln; Royal Scottish National Orch.; John Mauceri, cond / Piano Quartet / Philharmonic Piano Quartet Berlin: Daniel Stabrawa, vln; Matthew Hunter, vla; Knut Weber, cello; Markus Groh, pno / Sony Classical 19075869752 In the Piano Quartet, Elfman was lucky to get the highly gifted chamber ensemble of the Berlin Philharmonic. The first movement, “Ein Ding,” sounds a bit like minimalism due to its moto perpetuo rhythm in the opening, but Elfman interrupts it with pauses and overlays a long melodic theme played in whole and half notes over it. Rapid string tremolos introduce the development section. Still, the echoes of such minimalist composers as Terry Riley (whose music I like far more than that of Philip Glass) come and go throughout this movement. There are some lovely solos for the three strings, but in this movement, at least, the piano is treated more as a rhythmic motor than as a solo instrument.

In the Piano Quartet, Elfman was lucky to get the highly gifted chamber ensemble of the Berlin Philharmonic. The first movement, “Ein Ding,” sounds a bit like minimalism due to its moto perpetuo rhythm in the opening, but Elfman interrupts it with pauses and overlays a long melodic theme played in whole and half notes over it. Rapid string tremolos introduce the development section. Still, the echoes of such minimalist composers as Terry Riley (whose music I like far more than that of Philip Glass) come and go throughout this movement. There are some lovely solos for the three strings, but in this movement, at least, the piano is treated more as a rhythmic motor than as a solo instrument.