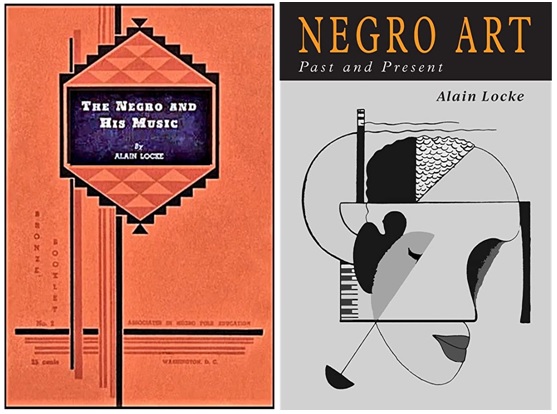

THE NEGRO AND HIS MUSIC / By Alain Locke, Ph.D. (Associates in Negro Folk Education, Washington D.C., 1936, 152 pp. available for free reading online at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015009742886&view=1up&seq=152)

NEGRO ART PAST AND PRESENT / By Alain Locke, Ph.D. (Associates in Negro Folk Education, Washington D.C., 1936, 122 pp., republished by Martino Fine Books, 2020, available at https://www.amazon.com/Negro-Art-Present-Alain-Locke/dp/1684225035)

Here is my contribution to Black History Month, a review of two once-important but now-neglected books on African-American art and music by one of the most important but also now neglected writers of the Harlem Renaissance, Dr. Alain LeRoy Locke, Ph.D.

Born Arthur Leroy (small r) Locke in Philadelphia on September 13, 1886, he changed his first name at age 16 to Alain LeRoy (capital R). After graduating high school, he attended Harvard where he earned degrees in English and Philosophy; then, in 1907, he became the first African-American to be selected as a Rhodes Scholar at the University of Oxford—and the last one selected until John Edgar Wideman and John Stanley Sanders were chosen for this honor. Three years later he attended the University of Berlin, so he was clearly a man with a first-class mind.

Alain Locke

After receiving an assistant professorship at Howard University in 1912, Locke returned to Harvard in 1916 to work on his doctoral dissertation, The Problem of Classification in the Theory of Value. He was invited to be guest editor of the March 1925 issue of Survey Graphic for a special edition titled “Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro.” In December 1925 he expanded this in a book titled The New Negro which also contained writings by other authors. The book was so positively and powerfully received that it launched what became known as the Harlem Renaissance, in which literate, modern-minded black men and women came to the fore in a cultural revolution against the stereotype of blacks as earthy and funny but dumb and uncultured. Sadly, as we know from history, the national backlash of American society to the Harlem Renaissance was largely negative. Even as late as the early 1970s, the joke was “What do they call a black nuclear physicist down South?…A n–ger!” (That is the actual joke. I do not endorse or approve of the language in it, though it’s true.) I’ve cleaned up and uploaded Locke’s contribution to the book as an Adobe PDF file. If you download it, you will discover that it s formatted to be printed out as 2-sided pages which, when folded in order, will make a neat little booklet. You can download it HERE –The New Negro.

Within these 14 pages you will find an encapsulated version of Locke’s view towards the Harlem Renaissance. It is a rather Pollyanna-ish view of the situation:

The migrant masses, shifting from countryside to city, hurdle several generations of experience at a leap, but more important, the same thing happens spiritually in the life-attitudes and self-expression of the Young Negro, in his poetry, his art, his education and his new outlook, with the additional advantage, of course, of the poise and greater certainty of knowing what it is all about. From this comes the promise and warrant of a new leadership…The day of :aunties,” “uncles” and “mammies” is equally gone. Uncle Tom and Sambo have passed on, and even the “Colonel” and “George” okay barnstorm roles from which they escape with relief when the public spotlight is off.

I understand his enthusiasm, but unfortunately, Locke was wrong. Even by the time this book was published, the white establishment had invaded even Harlem, the largest black bastion in North America, and taken over its entertainment district. The smaller night clubs and bistros formerly owned by blacks after World War I were gone, and the larger venues like the Kentucky Club and the Cotton Club were owned by whites. Except for the cooks, waiters and entertainment, there were no colored faces in their audiences. They were entirely white. And of course we all know now how blacks continued to be treated both in society and in the movies, as servants who had to shick-and-jive their way through the script. Just remember Stepin Fetchit for an example of the black caricature that was still permeated in the film business, or the way Louis Armstrong and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson were portrayed in films, as “yowzah”-spouting servants.

Among the writers and artists who flourished in the New York area during this period were Jean Toomer, Jessie Fauset, Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Zora Neale Hurston, Eric D. Walrond, Marcus Garvey and Countee Cullen. Black musicians like Louis Armstrong and James P. Johnson were also “grandfathered” into the movement. The oldest member, by far, was sociologist, historian and Pan-African civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois, yet it was the younger Locke who was considered the father of the movement. Du Bois and Locke had arguments, however, over the correct social functions of black art. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Du Bois thought it was a role and responsibility of the Negro artist to offer a representation of the Negro and black experience which might help in the quest for social uplift. Locke criticized this as “propaganda” and argued that the primary responsibility and function of the artist is to express his own individuality, and in doing that to communicate something of universal human appeal.”[1]

This was the beginning of the slowly evolving idea of musical and literary artists as social justice warriors, but it took decades for black artists to finally assert themselves in this respect. During Locke’s lifetime, there were precious few who dared buck the system, the most prominent being the great bass and actor Paul Robeson, and he only did so due to his indoctrination in Soviet Communism. But of course the black bop musicians of the 1940s were also rebels, although quieter ones. Their rebellion was in their art, creating a method of playing jazz that was too complex and difficult for most white musicians to absorb. Yet it still took the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s to put the finishing touches on what the Harlem Renaissance had started.

Nowadays we still have a split in the aesthetic philosophies of young black artists. A great many follow Locke’s example, which was to use their art, music and poetry to express their inner feelings but try to make it universally appealing, but there are a great many, both black and white (and nowadays also Latino) who feel it’s their duty to expound their personal political opinions in their music. I can’t tell you how many CDs I’ve been offered for review in which the focus of the album is not necessarily the music but a political message. This is even true of some classical CDs, but the overwhelming number are jazz. Nonetheless, I agree more with Locke than Du Bois on this point. Branding your artistic creation with a political message does not just damage it, it dates it. Just to cite one example, does anyone really care anymore about Nelson Rockefeller’s response to the Attica riots that prompted Charles Mingus to name one of his pieces after it? On a larger scale, the Du Bois vs. Locke argument can be compared to two Mexican artists of the 1930s and ‘40s who were lovers, muralist Diego Rivera and painter Frida Kahlo. Nearly all of Rivera’s murals were political, specifically touting the Soviet Communist system as a vast improvement on capitalism and specifically the workings of the Mexican government, while Kahlo’s paintings were intensely personal and almost shockingly powerful. Rivera is still studied in university courses, particularly by those who still hold a pro-Communist viewpoint, but by and large he is forgotten while Kahlo is revered as one of the greatest and most original artists of the 20th century.

Ironically. Locke is all but forgotten today while Du Bois is known almost universally. There are two reasons for this. The first was that Locke was homosexual and spent a great deal of time trying to convert young Renaissance writers and poets (especially Hughes) into being lovers, and this did not sit well with the younger members of the group. The second is that, unlike Du Bois, Locke was no self-promoter. On the contrary, he tended and preferred to stay in the background, so much so that by the time these two books were published by a small publishing house in Washington, D.C., it was a revival of interest in the man in the shadows. The books received good critical acclaim but, due to distribution problems, were not always available for people to buy and read. Arno Press and the New York Times reissued both books as a single volume in 1969, but that, too is out of print. Negro Art Past and Present was reissued by Martino Fine Books in 2020 and thankfully, this edition is still in print. In the header above, I have supplied a link to the full text of The Negro and his Music which can be read for free online.

Locke was a meticulous reader and listener who examined everything he wrote about in minute detail. processing it and rightfully declaring that Negro art and especially music, particularly jazz and the blues, were the wave of the cultural future, not only in American but globally. We now know that is was true insofar as jazz went, but as I pointed out in my book From Baroque to Bop and Beyond, most composers (but primarily Europeans) have fought the fusion of jazz and classical music because of the more advanced and technical aspects of modern classical, including the 12-tone and other modern schools which are incompatible with jazz, yet the trend continues to the present day.

The first of Locke’s books is, of course, the one primarily centered around music, and by and large he does a good job of covering all the bases. He was also one of those rare academics who could write in a style that was attractive and easy to read by the general public. He does not hit one over the head with “academic” writing of the sort that drips from the noses of college-professor books nowadays by both white and black authors but, on the contrary, tells a compelling story and makes his personal views known. Because his writing is so detailed and so compelling, he forced me to examine the recordings—particularly the early recordings of 1909-1926, which preserve a style of singing and method of performance that no longer exists—by the Fisk University Jubilee Singers. Of course the Jubilee Singers are still around, and it’s wonderful to hear them perform because (1) they’re using the original scores compiled in the 1870s, which were taken down directly from folk (congregational) performances of the time, and (2) you get to hear the whole choir including women’s voices whereas the early recording companies only used a male quartet, but the style of singing group spirituals has changed so drastically in the intervening years, now being influenced by gospel-blues and other modern styles, that to compare performances by the two groups is like night and day. The musical style of the early Fisk singers sounds entirely different from what we hear now, to the point where it is really not even possible to reconcile them. In short, both are good in their own way, but the earlier Fisk singers were much more authentic, presenting the way spirituals (as well as minstrel songs like James Bland’s Golden Slippers and Stephen Foster’s Old Black Joe) were probably sung in their original state.

So far, so good, and Locke’s two chapters on the era of minstrel shows in America are chock full of interesting and important information as well as a clear description of the difference between the two. The earlier style, which ended in the early 1870s (just after the end of the Civil War), was full of good songs, good vibes and respect between black and white performers, while the era 1875-1900 was full of cheap tunes, demeaning lyrics that devalued Africa-Americans, and the use of blackface to present blacks as cheap, ignorant drinkers and gamblers and nothing more. This unfortunately bled into the early decades of the 20th century, yet as Locke points out, the “dumb coon” stereotype of the minstrel shows was carried over to present dumb Italians, Jews, Swedes, Irish and Eastern Europeans during the vaudeville era. He also suggests, which is true, that Jewish entertainers in particular wore blackface not as a means of demeaning blacks but to celebrate their good qualities as well as to subtly signal that they suffered the same prejudice in society that blacks did if they were known to be Jews. (Even as late as the 1950s, Groucho Marx was denied membership in a country club he wanted to join so that his daughter Melinda, who was half-Jewish, could use their pool to swim. Groucho’s retort was, “Can the non-Jewish half of her at least use a part of the pool?”) Of course, today’s revisionists don’t understand this, thus even when they see a film clip of Al Jolson in blackface reading a Hebrew newspaper and winking at the camera, or see Eddie Cantor in blackface introducing the extraordinarily talented Nicholas Brothers to a national audience in one of his films, they don’t make the connection. Plain and simply, these two Jewish entertainers, Jolson and Cantor, were the last two to use blackface even into the 1940s, but they did it to present a solidarity with blacks, not to demean them.

Locke is somewhat sketchy on the ragtime era although he does mention, in passing, Scott Joplin and one or two other composers. Where he runs into trouble is in trying to describe the birth of jazz. He correctly attributes it to Louisiana and specifically New Orleans, but then throws 90% of the credit to blues publisher W.C. Handy. In this instance, however, I don’t altogether blame him. Handy was his own best promoter and liar about his importance in the development of jazz via the blues, and many of the blues he published under his name were simply stolen from street singers who had no legal recourse to sue him. Jelly Roll Morton specifically picks on Handy for telling him, during the early 1910s, that you could not notate the slurs and other rhythmic differences in blues and jazz tunes, Morton showed him how to do it; he had been doing it himself for some years by that time.

But alas, the name of Jelly Roll Morton appears nowhere in Locke’s book, as if he never even existed. This puzzles me for one reason, and that is that Morton’s Victor recordings were well distributed and pretty good sellers. I can understand that Locke probably never heard Morton’s early acoustic records or his few sides for Vocalion, but the Victors were a rich musical legacy that he should have known about. On the other hand, Northern blacks and especially New York residents like Locke often looked down their nose at the Southern styles of jazz. Another for-instance, he raves about Louis Armstrong but doesn’t put in a single word about Joe “King” Oliver, Armstrong’s mentor, even though Oliver’s band played in New York City on a regular basis between 1926 and 1930 (tenor saxophonist Lester Young even got his start in one of Oliver’s bands).

But there are some other strange quirks in the book. Perhaps the most glaring is his insistence that the tango is an “Afro-Cuban” dance rhythm. I don’t understand this at all, since by the time this book came out in 1936 it was well known that the tango originated in Argentina; in fact, Carlos Gardel, the most famous tango singer of all time, had already died by that time, and his records were everywhere. And then there are the strange misdates and wrong names in the book. Depending on what chapter you’re reading, or what portion if a chapter you’re reading, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue premiered in both 1923 AND 1924. He praises, in passing, a group he calls the “Dixieland Orchestra” without saying which one it was, then suddenly identifies it as “LaRocca’s Dixieland Orchestra”—meaning, of course, the Original Dixieland Jazz BAND. Jimmie Lunceford’s first name is spelled either a Jimmie, the correct way, or Jimmy depending on his whim of the moment, but Benny Goodman’s first name is always misspelled as Bennie. He never once mentions the genius jazz pianist Art Tatum in his text, but in the listening guide at the end of one chapter we suddenly see five or six Tatum recordings recommended without a word as to who he was or why we should be listening to them. On the positive side, I was very happy to note that Locke was a fan of white musicians who played in the black style, even if, as he says, they never really get the loose rhythmic inflections 100% right. In this respect he praises Red Norvo, Red Nichols and “Leon” Beiderbecke (he must have known that he went by the name of Bix!) as well as pointing out that the 1926 Goldkette band was one of the great pioneers of ensemble jazz writing and playing. He is also right in saying that, as great an improviser as Louis Armstrong was, that the majority of his improvisations are rhythmic and not really newly improvised choruses that created new melodies, as in the case of Coleman Hawkins, Teddy Wilson, and other soloists of the day who he admired. (Come to think of it, in addition to ignoring Morton, he also ignored Sidney Bechet, whose “New Orleans Feetwarmers” sides were released by Victor in 1932. I really don’t think he liked the authentic New Orleans jazz very much.)

Where Locke is truly helpful and educational is in his listing of works he considers to be “classical jazz” in the sense of an integration of at least jazz rhythms (improvisation in any classical music, at that time, was strictly taboo), and in this case he brings up several names who don’t get much attention today, like Otto Cesana, Van Phillips and Reginald Foresythe as well as some heavily jazz-based pieces by Louis Gruenberg that I hadn’t known existed. Here are links to some of the most interesting and original of them:

Otto Cesana: Negro Heaven / Fabien Sevitzky conducting the Indianapolis Symphony Orch.

Louis Gruenberg: The Daniel Jazz / Paul Sperry, tenor; New York Virtuosi Chamber Symphony, Kenneth Klein, conductor

William Grant Still: Sahdji – Ballet / Howard Hanson conducting the Rochester Philharmonic Chorus & Orchestra

Locke correctly states that although he admired Gershwin for his love of jazz, his Piano Concerto somehow misses the mark of true Negro feeling and his opera Porgy and Bess contains too much “Puccini and Wagner.” He also points out that although Liszt was a composer who believe in improvisation, his musical style does not mix at all well with jazz when compared to J.S. Bach. This, of course, was proven not only in his own time but decades later when French pianist Jacques Loussier began his “Play Bach” jazz concerts. All of this reveals a finely-tuned musical mind though he purposely does not get too deeply into technical descriptions of the music. He apparently saw his job as that of a tour guide, not a musical analyst.

The last chapter of this book, “The Future of Negro Music,” lays more heavily into the creation of full-scale concert works, even if they lack jazz elements. Locke explains his reasoning for this and, although history has proven him wrong, I understand how he felt about the matter in 1936, the early years of the Swing Era, that jazz, even the most artistic jazz, was too tightly bound to popular music to be considered true art music, no matter how exciting, vital or meaningful. Since he lived until June 1954, however, he may have changed his views, having seen and heard first hand the bop and cool jazz revolutions which elevated jazz above popular music into its own realm. Yet here he also reverts to his Pollyanna views, expecting the Metropolitan Opera to hire Marian Anderson sometime soon when in fact she didn’t make her Met debut until after his death, and predicting the widespread acceptance of symphonies, ballets and concertos written by black composers to become part of the standard repertoire—which they still haven’t. Despite all of these quibbles, however, The Negro and his Music is a brilliant book, insightful and precisely detailed as to most of the musical styles that evolved from Negro culture, and a must-read for anyone interested in the musical aesthetics of the period 1909 (the year of the first Fisk Jubilee Quartet recordings) through 1936.

Moving on to Negro Art Past and Present, this is a more—how shall I put it?—esthetically complete and integrated (in the abstract rather than the racial meaning of the word) text, in part because the history of art is the history of art. Despite widely different styles and fields of visual art, its trajectory is less cluttered with too many competing styles at any one time, even in the early 20th century when Locke was alive and wrote this. You had your representational art (art that looked realistic), your surreal art (art that looked like real objects but were skewered or presented in a way that defied both perspective and physics), and your abstract art, which ranged from the broken forms of Picasso to the wholly abstract use of geometric shapes like Kandinsky. Yes, there were subtle modifications to these forms, as in the paintings of Arthur Rackham, Gustav Klimt, Tamara de Lampicka and Georgia O’Keefe, yet in one sense or another their work fits into one of the three general styles mentioned above. You might, however, describe the work of these four artists as being halfway between representational and abstract, and this is where much of African art also falls.

Locke makes a strong case in arguing that many centuries ago African artists produced the most sophisticated art:

at least it is the most sophisticated modern artists and critics of our present generation who say so. And even should they be wrong as to this quality of African art, the fact still remains that there is an artistic tradition and skill in all the major craft arts running back for generations and even centuries, among the principal African tribes, particularly those of the West Coast and Equatorial Africa from which Afro-Americans have descended. These arts are wood and metal sculpture, metal forging, wood carving, ivory and bone carving, weaving, pottery, skilled surface decoration in line and colorof all these crafts. in fact everything in the category of European fine arts except easel painting on canvas, marble sculpture and engraving and etching.

Thus, Locke argues,. the American Negroes who are the descendants of the Africans, even after three to four generations of enslavement, have at least a proclivity towards these arts that only needs to be brought out through study and practice, that the Afro-Americans are as much “naturals” at this sort of art as they are physiologically adept at physical movement and song. I certainly can’t argue with the latter assertion as it has been proven over and over again not only in my own lifetime but going back, at the very least, to the creation of jazz as a fusion of various earlier black musical forms, but in the back of my mind I can’t help feeling that Locke assumed a bit too much when it came to “racial memory” in the physical arts. Surely there were some among them, as there are in any race, who have that proclivity, but I also have the feeling that just because Joe has a great talent for artwork it doesn’t follow that his brother Jim or his sister Sue will also have anything close to his relent. Many are the families that turned out gifted artists who were complete anomalies when compared to everyone else in that family, regardless of race. I’m not arguing race at all but rather the argument that what your forefathers did well should be something you could also do well with a bit of training.

Where I completely agree with Locke is in his description of how blacks were represented in paintings et. al. until the end of the 18th century, as exotic, highly prized friends, household members or high-grade servants like pages and companions to royalty, then suddenly changed into something sub-human due to the curse of slavery. Slavery dehumanized the black man and woman, took away their intelligence, grace and even many of their cognitive functions, in order to make cotton-pickers, stevedores and “mammies” of them. The result of this dehumanization process was the white overlords’ conception of them as machines that did not require a motor or another human’s interaction to make them work. Locke puts it very well:

When a few Negroes did get contact with the skilled crafts, their work showed that there was some slumbering instinct of the artisan left, for especially in the early colonial days, before plantation slaves had become dominant, the Negro craftsmen were well-known as cabinet-makers, marquetry setters, wood carvers and iron-smiths…But the Negro’s artistry wa turned completely inside out. His taste, skill and artistic interests in America are almost the reverse of his original ones in Africa. [Bold print mine.] In Africa the dominant arts were the decorative and the craft arts…rigid, controlled, disciplined; heavily conventionalized, restrained. The latter [in America] are freely emotional, sentimental and exuberant, so that even the emotional temper of the American Negro is generally credited with a “barbaric love of color,”—which indeed he does seem to possess…What we have then thought “primitive” in the American Negro, his naïve exuberance, his spontaneity, his sentimentalism are, then, not characteristically African and cannot be explained as an ancestral heritage. They seem the result of his peculiar experience in America and the emotional upheavals of its hardships and their compensatory reactions.

Since I’ve not made a detailed study of physical art within all the various cultures, I cannot say how much of what Locke says here is unquestionably true, but although he was clearly too young to have any memory of slavery, he came from a generation that certainly had parents and grandparents who were slaves, thus I take him at his word. He clearly knows much more about this subject that I do, In this book, then, he is the master and I the pupil.

Clearly, there was at that time a rich crop of African-American artists producing quality work, among them Charles Alston, John Biggers, Robert Blackburn, Margaret Burroughs, Elizabeth Callett, Ernest Crichlow, Beauford Delaney, Aaron Douglas, Wilmer Jennings, William H. Johnson, Lawrence Jones, Lois Mailou Jones, Ronald Joseph and it speaks volumes about our modern education system that most of them as well as their ancestors and successors are not nearly as well known as their white contemporaries, both male and female. Perhaps this is because much of their art fell into the already-established categories mentioned above, primarily in the fanciful-representational field or the somewhat abstract style which later came to be associated with the “primitive” art of a white painter like Grandma Moses. Looking over some of the examples available online, I chose the two following because they struck me as among the most original as well as the most arresting visually.

“Can Fire in the Park,” Beauford Delaney

“Moon Masque,” Lois Mailou Jones

But I am getting ahead of myself, and Locke. He patiently covers the earliest African-American artists in America and explains how, despite their acquisition of superb artistic skills in both painting and sculpture from European artists, their work portrayed either historical images or portraits of white people. One sculptor who closely studied Rodin’s work was praised by him, yet most of the work thus produced had no black-centric theme. There were, however, two women sculptors who dared to break the mold by producing powerful, Negro-centric works: Edmonia Lewis (1844-1907), whose Forever Free depicted a powerful freed black man defiantly raising his left hand holding the broken chains of his bondage and protecting his mulatto wife with his right, and Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877-1968), whose Ethiopia Awakening (1914) was probably the first representation of a proud, strong African woman produced by any black American artist (see below).

“Forever Free,” Edmonia Lewis

Even more interesting, however, was the “Negro Art Revival” which took place almost by accident. A British military expedition sacked and burned the ancient city of Benin in West Africa, Locke tells us,

as punishment for tribal raids and resistance to colonial penetration of the interior of that region…cartloads of cast bronze and carved ivory from the temples and the palaces were carried to England, and accidentally came to the auction block, Discerning critics recognized them to be of extraordinary workmanship in carving and casting…Acting without official orders, a young curator of the Berlin Museum bought up nearly half of this unexpected art treasure….duplicates were traded to form the basis of the famous collection at Vienna, ans the young scholar, Felix von Luschan, by a four-volume folio publication on this art and its historical background, easily became the outstanding authority of his generation on primitive African art.

Equally important was the exposure of a group of young, talented painters and art critics in Paris to excellent specimens of native African fetish carvings from the French West Coast colonies. At first their interest was purely technical and academic, but as they became more familiar with them they spurred the creation of both the Cubist and Surrealist art movements. Thus, just as African-American music permeated into the mainstream via ragtime, the blues and jazz to create an entirely new art form based on a looser use of syncopation and the creation of spontaneously improvised choruses, African-European art works created what we now know as the modern school of art. Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Jacques Lipchitz, Chaim Soutine, Salvador Dali and particularly Amedeo Modigliani ALL came out of this art collection, which was given the French title of “L’Art Nègre.”

“Ethiopia Awakening” (1914), Meta Vaux Warrick

In a sense, then, at least half of the entire modern world of musical and visual art aesthetics was in one way or another created by black cultures. For better or worse, however, these school os aesthetics have long butted heads with the more cerebral forms of music and art created in Europe, primarily by Germans and Russians, which was far more complex in both structure and form and thus rejected the heady passion of what they perceived as an alien and primitive race. Theodor Adorno, although a brilliant man, was in the vanguard of those culture snobs who did their level best to trash jazz and anything connected with it as an “emasculation” of human intellect—at least, until he discovered Duke Ellington, whose music he liked because to him it represented “stabilized jazz,” its form and structure presenting “tasteful jazz as an appropriation of the conventions of musical impressionism, of the style, that is, of composers such as Debussy, Ravel, and Delius.” Unfortunately, there does not appear to be any such parallel in the acceptance of black-produced art by the culture snobs after the early African-American artists stopped doing wholesale imitations of white art. Of course, the cubists and surrealists met with strong opposition at first, but by the early 1930s these schools had become so mainstream that there was no point in fighting them any further. Whether you liked them or not, they were here to stay, but even in this period the white artists whose styles grew out of Negro art were usually much more highly praised than African-American originals.

Ironically, it was a white American artist, Winslow Homer, who in The Gulf Stream was the first to portray a black man as a strong person, physically (obviously) but also someone in charge of the situation rather than a half-fearful “coon” begging for Whitey to come and save him. This in turn helped such black artists as Robert Henri, George Luks, George Bellows and William H. Johnson, a sort of protégé of Luks who gave him $600 (quite a sum in those days!) out of his own pocket to go and study in Europe when Johnson had a promised foreign scholarship suddenly revoked without warning or explanation. These were not timid artists who stayed within the conventions imposed on them by white culture, but daring men who broke the mold. One of many such powerful works which this group created was Bellows, 1923 lithograph, The Law is Too Slow, showing a black man being burned at the stake by some “good ole boys” (see below).

“The Law is Too Slow” (1923), George Bellows

I could go on and on in this vein, but this would be pretty much summarizing each chapter and showing examples. I will only say that the one white artist who portrayed the disgusting dehumanization of slavery who was left out of Locke’s book was, of all people, J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), the first impressionist painter in history. His 1840 painting, The Slave Ship speaks volumes of the way blacks were treated by whites. The painting represents a real-life event which took place in 1781when the British ship Zong encountered a typhoon and began throwing their dead and dying black “cargo” overboard. Critic John Ruskin, who first owned this painting, wrote that “If I were reduced to rest Turner’s immortality upon any single work, I should choose this” (see below).

The Slave Ship” (1840), J.M.W. Turner

The biggest drawback of this book is that there are no illustrations of the artwork being described, not even black-and-white drawings or woodcuts. This was probably due to the book being put out by such a small publisher, during the Depression, with a small budget to work with. Happily, we now have the Internet, and several (but by no means all) of the artists and/or specific pieces of art named therein can be found online.

One particular portion of a paragraph on p. 94, in the next-to-last chapter, really caught my eye—as much for what he didn’t say as much for what he did. Here is the pertinent section:

The peak of almost every well-known strain of African art is definitely associated with the heyday of some feudal African dynasty that became rich and powerful through conquest of other African peoples [bold print mine], and concentrated their wealth and sometimes their religion on the patronage of some art style and tradition.The famous Benin art thus centers in the rise of the great alliance of the Benin warlords with the priests of the Ifa or Yoruba serpent-cult religion on the West Coast, an empire that was at its height in the Sixteenth Century but lasted in its interior stronghold till Benin’s downfall in 1897 at the hands of a British punitive expedition,

And what did these successful marauding countries do with the people living in the countries they conquered? They either killed them or enslaved them, much as the ancient Greeks did; and just as we now complain that the great majority of Greek art, music and philosophy was created by native Greeks who had the “luxury” of making foreign captive slaves do most of their work, so too the successful African nations were able to produce great art because they, too had slaves from conquered nations to do their work for them.

So tell me, except for the fact that black slaves were extradited forcibly to foreign white-run countries to do the bidding of their new masters, how exactly is this different? Perhaps by degree; since the African oppression was black-on-black, they were at least a similar race oppressing another. But that is all. My point is that many of the outraged modern African-Americans who are stil upset that America had slavery until 1865 should just accept the fact that it’s now over, except that there is one thing that I can understand their being upset about. Once the other slave-owning countries in Europe abolished slavery, they made an effort to integrate the freed slaves and their descendants into their society, whereas white Americans kept demeaning, marginalizing and insulting black Americans into the late 20th century, nearly 150 years after the official end of slavery in America. This is the real basis of their discontent and anger, and I for one don’t blame them, but once again it was their religion that perpetuated racial strife. I clearly remember the chilling sound of a white Southern woman talking on the radio news during the Civil Rights era of the mid-1960s saying, “You know the Bible says that segregation is right,” and of course there is the famous quote from Paul in the New Testament: “Slave, obey your master.” As descendants of Puritans and other extreme religious sects who either escaped or were deported to America because their country of origin had enough of their extremist crap, they simply did not and would not let go of the old attitudes, because their interpretation of the Bible reinforced their mindset. The number of those who still think this way is much, much smaller now than it was even in 1980, but they still do exist. Even so, they have to accept the fact that slavery was the way ALL economies in the world ran into the early 19th century, and then when these countries abolished slavery they simply co-opted other poor countries in both Africa and Asia (primarily India and Turkey, but also Indo-China) as “colonies” that they could plunder, having the natives there do the work and not even have to bother MAKING them “slaves.”

To use a modern-day colloquialism, “Just sayin’.”

To put it succinctly, both of these are really outstanding books that should be required reading in high schools across America. Locke was not only a great wool-gatherer of facts and a good judge of both musical and physical art aesthetics, but he lived at exactly the right time to judge both what had come just before his birth and, more importantly, experience the evolution of African-American art and music first hand, as it happened. I don’t know if he ever wrote an article about John Hammond’s first “Spirituals to Swing” concert at Carnegie Hall in December 1938, but this, like Benny Goodman’s concert in January of that same year, were breakthroughs for the presentation of jazz as a serious musical art form in one of America’s most hallowed halls. The bottom line is that Locke deserves to be remembered and honored for his invaluable contribution to African-American aesthetics. Ignoring or marginalizing him is a crime against both history and the analysis of a finely-tuned mind.

—© 2023 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter or Facebook

Check out the books on my blog…they’re worth reading, trust me!

[1] https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/alain-locke/

But for whatever reason, Hayes was continually being shafted by the record companies. He had to pay out of his own pocket for his 1917 recording session with Columbia, where they only pressed “personal records” for him in limited quantities. We should be grateful that, somehow, copies survived. If you go to the Discography of Historical American Recordings and enter Hayes’ name, you will see the results of his frustration. In addition to an untitled and therefore undocumented test pressing he made for Victor in 1917, there were three rejected masters from 1923, five from 1927 and four from 1936. Apparently, Victor didn’t think that this voice which recorded so well was marketable.

But for whatever reason, Hayes was continually being shafted by the record companies. He had to pay out of his own pocket for his 1917 recording session with Columbia, where they only pressed “personal records” for him in limited quantities. We should be grateful that, somehow, copies survived. If you go to the Discography of Historical American Recordings and enter Hayes’ name, you will see the results of his frustration. In addition to an untitled and therefore undocumented test pressing he made for Victor in 1917, there were three rejected masters from 1923, five from 1927 and four from 1936. Apparently, Victor didn’t think that this voice which recorded so well was marketable. During that same year, Hayes returned to the U.S. to make his debut with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Pierre Monteux in a program including songs by Berlioz and Mozart as well as spirituals. By the mid-1920s, he no longer had to pay to put on his own concerts; on the contrary, he was earning around $100,00 a year, which equates to about a million dollars a year in today’s money.

During that same year, Hayes returned to the U.S. to make his debut with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Pierre Monteux in a program including songs by Berlioz and Mozart as well as spirituals. By the mid-1920s, he no longer had to pay to put on his own concerts; on the contrary, he was earning around $100,00 a year, which equates to about a million dollars a year in today’s money. Things did not go well afterward, however, In 1931, Hayes tried to end the practice of segregated seating at several concerts, including Washington, D.C.’s Constitution Hall, but met with hostility and resistance. In 1933 he had to cancel all concerts in Germany and refuse to return once the Nazis took power. But there were others, including an incident in July 1942 when he was assaulted in Rome, Georgia by not the Ku Klux Klan but by the local police. Again according to Christopher Brooks, “The news of this ‘beat-down’ was heard around the world. The New York Times headline read, ‘Beaten in Georgia. Says Roland Hayes, Negro Singer.’ Both he and his wife were put in jail. Civil rights icons like Walter White, Thurgood Marshall, Merrill McLeod Bethune and many others screamed to the top of their lungs about this dastardly deed.” First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt chose to work behind the scenes, but she did her part including resuscitating Hayes’ career, which even by the mid-1940s was on a downward trajectory. True to the Henschel method of singing, Hayes’ voice remained firm, showing no trace of unsteadiness even into his 80s, but the high range lost its brightness and the tone became gray in quality.

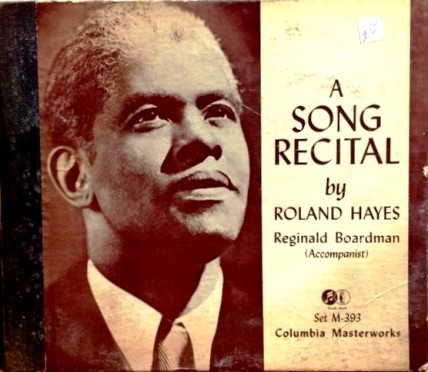

Things did not go well afterward, however, In 1931, Hayes tried to end the practice of segregated seating at several concerts, including Washington, D.C.’s Constitution Hall, but met with hostility and resistance. In 1933 he had to cancel all concerts in Germany and refuse to return once the Nazis took power. But there were others, including an incident in July 1942 when he was assaulted in Rome, Georgia by not the Ku Klux Klan but by the local police. Again according to Christopher Brooks, “The news of this ‘beat-down’ was heard around the world. The New York Times headline read, ‘Beaten in Georgia. Says Roland Hayes, Negro Singer.’ Both he and his wife were put in jail. Civil rights icons like Walter White, Thurgood Marshall, Merrill McLeod Bethune and many others screamed to the top of their lungs about this dastardly deed.” First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt chose to work behind the scenes, but she did her part including resuscitating Hayes’ career, which even by the mid-1940s was on a downward trajectory. True to the Henschel method of singing, Hayes’ voice remained firm, showing no trace of unsteadiness even into his 80s, but the high range lost its brightness and the tone became gray in quality. Yet ironically, it was in 1941 that Hayes finally made records in America for an American label that were actually released. This was A Song Recital By Roland Hayes, an album of five 10” 78s on the Columbia Masterworks label, and not too surprisingly considering the demand, it sold pretty well. Despite the winding-down of his career and the fact that he turned 60 in 1947 Hayes continued to concertize, but by the mid-1950s he was only giving one concert a year, a schedule he would keep until his very last concert in the early 1970s. Despite his loss of vocal sheen and power, this is the period in which he made most of his recordings, a series of LPs for the Vanguard label, and unfortunately this is how posterity has largely judged him.

Yet ironically, it was in 1941 that Hayes finally made records in America for an American label that were actually released. This was A Song Recital By Roland Hayes, an album of five 10” 78s on the Columbia Masterworks label, and not too surprisingly considering the demand, it sold pretty well. Despite the winding-down of his career and the fact that he turned 60 in 1947 Hayes continued to concertize, but by the mid-1950s he was only giving one concert a year, a schedule he would keep until his very last concert in the early 1970s. Despite his loss of vocal sheen and power, this is the period in which he made most of his recordings, a series of LPs for the Vanguard label, and unfortunately this is how posterity has largely judged him. When you finish listening to all of these recordings, you will get not only a good perspective as to the condition of Hayes’ voice at various points in his career—great in the 1917-24 tracks, quite good in 1941, decently good ion 1956-59—but also a perspective on his artistry. Despite the fact that the Pagliacci aria is a carbon copy of Caruso’s phrasing, the state of his voice in those years makes you sad that he didn’t sing more opera arias in his recitals.

When you finish listening to all of these recordings, you will get not only a good perspective as to the condition of Hayes’ voice at various points in his career—great in the 1917-24 tracks, quite good in 1941, decently good ion 1956-59—but also a perspective on his artistry. Despite the fact that the Pagliacci aria is a carbon copy of Caruso’s phrasing, the state of his voice in those years makes you sad that he didn’t sing more opera arias in his recitals.

AHO: Violin Concerto No. 2.* Cello Concerto Mo. 2+ / *Elina Vähälä, vln; +Jonathan Roozeman, cel; Kymi Sinfonietta; Olari Elts, cond / Bis SACD-2466

AHO: Violin Concerto No. 2.* Cello Concerto Mo. 2+ / *Elina Vähälä, vln; +Jonathan Roozeman, cel; Kymi Sinfonietta; Olari Elts, cond / Bis SACD-2466