CD 1: STRAUSS: Der Rosenkavalier: O, sei er gut, Quinquin…Die zeit, die ist ein sonderbar Ding. Ariadne auf Naxos: Sie lebt hier ganz allein…Sie atmet leicht…Es gibt ein reich / Orch. conducted by Manfred Gurlitt / BEETHOVEN: Egmont: Die Trommel gerühret! Freudvoll und leidvoll / Unidentified orch. & cond. / GOUNOD: Vierge d’Athènes. RUBINSTEIN: / Ernö Balogh, pianist / WAGNER: Lohenrgin: Du Ärmste kannst wohl nie ermessen / NBC Symphony Orch., cond. Frank Black / WOLF: Kennst du das Land. Frühling übers jahr. Und willst du deinen Liebsten. Wenn du, mein Liebster, steigst zum Himmel auf. In der Frühe. Auch kleine Dinge. Der Knabe und das Immlein. Er ist’s. Storchenbotschaft. An eine Aolsharfe. In dem Schatten meiner Locken. Gebet. Nun lass uns Frieden schliessen. Der Gartner. Du denkst mit einem Fadchen mich zu fangen. Heimweh. Schweig einmal still. Ich hab in Penna einen Liebsten. Anakreons Grab. Verborgenheit / Paul Ulanowsky, pianist

CD 2: STRAUSS: Ständchen. BRHAMS: Therese. Vergebliches Ständchen. BLECH: Heimkehr vom Feste. STRAUSS: Zueignung. PUCCINI: Tosca: Vissi d’arte.1 STRAUSS: Zuiegnung (2nd vers).1 Traum durch die Dämmerung.1 Ständchen (2nd vers).1 BRAHMS: Das Mädchen spricht. PFITZNER: Gretel. TCHAIKOVSKY: None But the Lonely Heart.2 JAMES ROGERS: The Star.2 SCHUBERT: Die junge Nonne. Der Doppelgänger. Liebesbotschaft. SCHUMANN: Aufträge. MENDELSSOHN: Morgengruβ. Venetianisches Gondollied. Neue Liebe. SCHUMANN: Der Nussbaum. BEETHOVEN: Wonne her Wehmut. Andenken. BRAHMS: Wiegenlied. Ständchen. MENDELSSOHN: Auf Flugeln des Gesänges. MOZART: Sehnsucht nach dem Frühling, K. 596. Warnung, K. 433 / Paul Ulanowsky, pianist except orchestral songs by NBC Symphony Orch., cond. by 1Frank Black & 2Nathaniel Shilkret.

CD 3: WAGNER: Wesendonck Lieder: Der Engel. Im Treibhaus. Schmerzen. Träume. SCHUMANN: Dichterliebe: Wenn ich in deine Augen seh; Und wussten s die Blumen; Das ist ein floten und geigen; Die alten bosen Lieder. SCHUBERT: An eine Quelle. Der Tod und das Mädchen. Der Jungling und das Tod. Auflösung. Die Forelle. Dass sie hier gewesen! Der Wanderer an der Mond. Im Frühling. Schwangesang. BRAHMS: Der Kranz. Es träumte mir. Frühlingslied. Wills du, dass ich geh? BACH-GOUNOD: Ave Maria.* BEETHOVEN: Neue Liebe, Neues Leben. MENDELSSOHN: Schilftlied. Frage. Der Mond. Lieblingslätzchen. Gruβ. Pagenlied. Die Liebende schreibt / Paul Ulanowsky, pianist except *RCA Victor Chamber Orch., cond. Richard Lert.

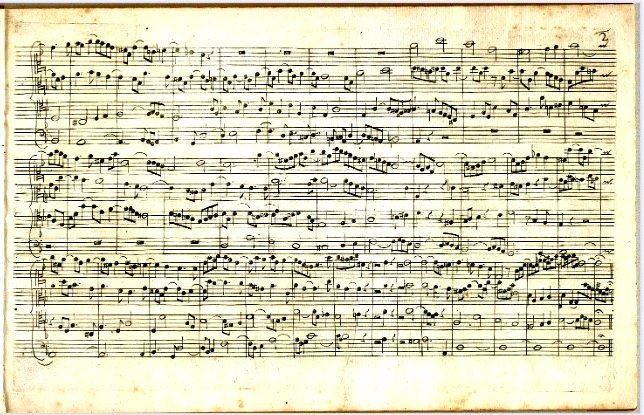

CD 4: BEETHOVEN: An die ferne Geliebte. MOZART: Als Luise die Briefe. Abendempfindung. Dans un bois solitaire. Die Verschweigung. BRAHMS: Dein blaues Auge halt. Komm bald. Bitteres zu sagen denkst du. Schon war, das ich dir weihte. Am Sonntag Morgen zierlich angetan. Der Gang zum Liebchen. Der Tod, das ist die kühle Nacht. Liebestreu. Frühlingstrost. Der Kuss. O wusst ich doch den Weg zuruck. Die schöne Magelone: Wie froh und Frisch. Bruno Walter speaks about Lotte Lehmann. BEETHOVEN: Egmont: Freudvoll und leidvoll. MOZART: Das Veilchen. SCHUBERT: An die Musik. WOLF: Anakreons Grab. BRAHMS: Botschaft. KARL GROOS: Freiheit, die ich meine / Bruno Walter, pianist / Lehmann reads her poem, “In alten Partituren. Lehmann speaks about her singing. WOLF: Gesang Weylas / Paul Ulanowsky, pianist / Lotte Lehmann, soprano / all of the above on Music & Arts CD-1279

Before I begin this review, some explanation is in order. Very early on in my discovery of older singers, I ran across Lotte Lehmann as Eva in excerpts from Die Meistersinger, and I liked them very much. I also came across her highlights from Der Rosenkavalier, an opera I generally dislike except for maybe 20 minutes’ worth of music, and I liked them, too. I also very much enjoyed her 1927 or ’28 recording of the Act II finale from Die Fledermaus with tenor Richard Tauber. But everything else I heard after that I found to be sung with a dull, unattractive voice despite her interesting interpretations.

Recently, however, I ran across a new transfer (on YouTube) of her recording of Die Walküre Act I with Lauritz Melchior and Bruno Walter, and I was taken aback. Why? Because in this transfer, her voice sounded as bright as on those other recordings mentioned above whereas every previous issue I’ve heard of this recording sounded dull and gray. Which led me to wonder, Was I misjudging her based on defective transfers of her records?

It turned out that I was.

Now, mind you, she did have several technical flaws. She went flat at times—both on studio recordings and live performances—and even as far back as the acoustic era she took too many breaths in the middle of phrases. This led me to believe that she never had a very well grounded vocal technique, which may account in part for her losing her notes above a B-flat by 1935. And even with the brighter sound, the voice was not a particularly beautiful one. In fact, I’d say it was no better in tonal quality than that of Vera Schwarz, a soprano largely forgotten today, or of mezzo-soprano Elena Gerhardt, one of the most celebrated lieder singers of the 1920s and ‘30s. Another Lotte who was her near-contemporary, Lotte Schöne, had a far prettier voice. But Lehmann had one thing going for her that is not apparent when you just listen to her recordings, and that was an exceptional stage acting ability. If you watch her speak one of the Marschallin’s monologues (as an old lady) on YouTube, you’ll see what I mean. You can’t take your eyes off her; her facial expressions and body language rival that of Feodor Chaliapin, and like Chaliapin she always claimed that, to her, the meaning of the words were more important than strict musical accuracy, but also like Chaliapin (who she sang with at least once, in a performance of Gounod’s Faust), the lessons she taught other singers took decades for the influence to show.

Now, mind you, she did have several technical flaws. She went flat at times—both on studio recordings and live performances—and even as far back as the acoustic era she took too many breaths in the middle of phrases. This led me to believe that she never had a very well grounded vocal technique, which may account in part for her losing her notes above a B-flat by 1935. And even with the brighter sound, the voice was not a particularly beautiful one. In fact, I’d say it was no better in tonal quality than that of Vera Schwarz, a soprano largely forgotten today, or of mezzo-soprano Elena Gerhardt, one of the most celebrated lieder singers of the 1920s and ‘30s. Another Lotte who was her near-contemporary, Lotte Schöne, had a far prettier voice. But Lehmann had one thing going for her that is not apparent when you just listen to her recordings, and that was an exceptional stage acting ability. If you watch her speak one of the Marschallin’s monologues (as an old lady) on YouTube, you’ll see what I mean. You can’t take your eyes off her; her facial expressions and body language rival that of Feodor Chaliapin, and like Chaliapin she always claimed that, to her, the meaning of the words were more important than strict musical accuracy, but also like Chaliapin (who she sang with at least once, in a performance of Gounod’s Faust), the lessons she taught other singers took decades for the influence to show.

Thus one can consider her analogous to Maria Callas, another outstanding stage interpreter whose voice left much to be desired in timbre and, sometimes, vocal control, the difference being that we have several film clips of Callas to show us what all the fuss was about. We don’t with Lehmann. All we have are the records, and that is an incomplete picture of the total package.

The funny thing is that famous musicians (including some very illustrious conductors) and music critics of her time) didn’t notice these flaws at all. Because she was both musical and dramatic in addition to her mesmerizing stage presence, they fell all over her. In fact, it’s been my experience that Lotte Lehmann admirers are often fanatics who will brook no criticism of her. As far as they’re concerned. she walked on water, and although I’ve come around to admiring what she had to offer I’m clearly not in that camp. Thus I would have to claim her as the greatest cult figure among classical sopranos. And now, to the recordings at hand.

Despite the presence of a few early electrical recordings (1927-32) on CD 1, the bulk of these come from the period 1936-1949, the latter made less than two years before her farewell concert and retirement at the age of 63. What I found interesting about the majority of the lieder recordings, which make up the bulk of this set, is that Lehmann almost never gave you a very subtle or “inner” interpretation of the lyrics; on the contrary, hers was a very excitable approach to German lied, quite the opposite of most of her peers. In An die Ferne Geliebte, for instance, she sounds almost continually excited and impulsive. By this time, too (1941), her vibrato had become a bit loose, not enough to be a constant annoyance, thank goodness, but not as tight or compact as it had been only five years previously. Yet her impulsive qualities certainly enlivens much of the songs she performs, particularly those of Mozart and Brahms. In repertoire like this, modern sopranos who sing lieder could learn something from her approach if not from her handling of the voice (there are far too many breaths taken in Abendempfindung) and, at 53, she already sounded like an old woman. She sings no higher than a G in Mozart’s Dans un bois solitaire, but that G sounds badly strained. I point these things out not to shame her but merely to indicate that she was working with a flawed instrument.

Another interesting point to consider is that her accompanists generally sound competent but emotionally neuter; they seem to want to leave all the expression to Lehmann rather than assert themselves in any meaningful way. I found this pretty interesting as well.

Lehmann’s impetuous delivery and quite fast tempi gives one cause to believe that music one might think was being rushed to fit the 78-rpm side, such as the two songs from Beethoven’s Egmont, were artistic choices she made and not the fault of the recording session director asking her to “pick it up a little.”

Once your ears become adjusted to her not-always-continuous phrasing and impetuous delivery, however, I think you’ll find her a very lively interpreter whose work carries much interest because of this phenomenon. Lehmann without her impetuosity would be as unthinkable as Caruso without his portamento scoops; it was her signature style of singing, and you either accepted it on those terms or rejected it entirely, There was no middle ground with her.

In her live 1938 recital of Wolf lieder, with the microphone somewhat backed off away from her, one gets a good idea of how the voice carried in a theater, and in 1938 her voice was still sufficiently bright in timbre (and secure up to a high Bb) that one realizes that, at something of a distance, you don’t notice the frequent breaths in the vocal line nearly as much as when the microphone was right in front of her. And much to my urprise, her performance here of Tosca’s “Vissi d’arte” is one of the finest I’ve ever heard.

Despite the flaws mentioned above, the compilers of this anthology have pretty much put Lehmann’s best foot forward for her, so to speak, revealing the solid musician and highly communicable artist who so engrossed two generations of listeners.

And now for the drawbacks of this set…thankfully, not many. The programming is for the most part very good, but I question the repetition of several songs just because they happened to have some rare radio transcription discs of her singing lieder with the NBC Symphony Orchestra directed by Frank Black. I don’t even like orchestral arrangements of lieder accompaniments to begin with, and Lehmann didn’t really interpret them any differently in these versions (in fact, since the orchestral versions are slower, I find them less interesting). I also questioned the inclusion of two such trashy pieces as the Bach-Gounod Ave Maria (who cares how she sang it? she didn’t have the kind of voice that one drinks in anyway) and Tchaikovsky’s None But the Lonely Heart. I would rather they had thrown those four tracks out, moved James Rogers’ The Star (a very cute song which she does well) from CD 2 to CD 3, and instead included two of her marvelous recordings of Eva’s music from Die Meistersinger instead. I also wish they had ended the set not with Wolf’s Gesang Weylas but with her outstanding recording of the “Liebestod” from Tristan und Isolde. Other than that, the selection of material and the programming are excellent.

Unfortunately, the sound engineer who processed the recordings did not do a consistent job in equalizing them to get the consistently bright sound of her voice. Some of the live songs are absolutely perfect, but several others are not, particularly not the NBC broadcast material which has a dull top end. This should have been corrected prior to release.

Be that as it may, this is, overall, an exceptionally fine introduction to Lehmann and her very personal artistry. If you’re already a fan you’ll probably want it for the many rarities here, and if you’re not, you just might change your mind when listening to it.

—© 2021 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter (@Artmusiclounge) or Facebook (as Monique Musique)

As for the music, it is fascinating and very well written. Charpentier did an excellent job of setting the text to music and making it work dramatically. The problem is that he and his librettist, Thomas Corneille, unfortunately chose to set almost the entire play to music rather than compressing it as Luigi Cherubini did a century later. This was a mistake on their part; even Monteverdi telescoped Orfeo ed Euridice for his early opera, as did Gluck a century and a half later. What takes about 75 minutes to perform as a spoken stage play takes, here, nearly two and a half hours to get through as a sung opera, and although, as I say, the music is generally excellent, it’s just a bit too much to make an effective opera.

As for the music, it is fascinating and very well written. Charpentier did an excellent job of setting the text to music and making it work dramatically. The problem is that he and his librettist, Thomas Corneille, unfortunately chose to set almost the entire play to music rather than compressing it as Luigi Cherubini did a century later. This was a mistake on their part; even Monteverdi telescoped Orfeo ed Euridice for his early opera, as did Gluck a century and a half later. What takes about 75 minutes to perform as a spoken stage play takes, here, nearly two and a half hours to get through as a sung opera, and although, as I say, the music is generally excellent, it’s just a bit too much to make an effective opera.

SMITH: Symphonies: No. 1, Gold; No. 2, Diamond; No. 3, Pearl / Wadada Leo Smith, tpt/fl-hn; Henry Threadgill, a-sax/fl/bs-fl; John Lindberg, bs; Jack De Johnette, dm / Symphony No. 4, Sapphire / Jonathon Haffner, a-sax/sop-sax repl. Threadgill / TUM Box 004

SMITH: Symphonies: No. 1, Gold; No. 2, Diamond; No. 3, Pearl / Wadada Leo Smith, tpt/fl-hn; Henry Threadgill, a-sax/fl/bs-fl; John Lindberg, bs; Jack De Johnette, dm / Symphony No. 4, Sapphire / Jonathon Haffner, a-sax/sop-sax repl. Threadgill / TUM Box 004