In 1995, Oxford University Press published Cats of Any Color, a collection of essays from famed critic Gene Lees’ Jazzletter as well as a manifesto against the rampant views of some black jazz musicians and critics that jazz is, and always was, a “blacks only” music, that all the innovations in the music came from blacks and no one else, thus only black musicians can or should play real jazz. There were several sources of this attitude, but at that time they came primarily from three people, jazz critics Amiri Baraka and Stanley Crouch and Wynton Marsalis, Crouch’s protégé and director of the Jazz at Lincoln Center program.

But that was then and this is now. Or is it? Both Baraka and Crouch are now deceased, but Marsalis is still with us and still in charge of Jazz at Lincoln Center, still espousing the same beliefs. Yet there were so many exceptions to his rule, even by Marsalis himself, that he made his claim that only blacks could “really” play jazz moot. After firing every white musician in the JALC band, and just before the band was to leave on a five-week tour in January 1994, Marsalis discovered that one of the black replacements for a white musician couldn’t hack the charts. Former lead alto saxist Jerry Dodgion was called on the phone by the band’s manager and asked to return for the tour. Dodgion named his price and accepted the offer. He was gracious in doing so. I’m sure there were many others who would simply have said No and hung up the phone.

And there were exceptions to his rule when he felt like it, such as one of Marsalis’ pet musicians, the late pianist Geri Allen, even though Allen performed and recorded for many years with a trio that included white bassist Charlie Haden (former member of the Ornette Coleman Quartet) and white drummer Paul Motian (former member of the 1960 Bill Evans trio). In 2017, Marsalis played as a guest soloist in a recorded concert with French soprano saxophonist Emile Parisien’s Quintet in Marciac, France; apparently, he feels that white Europeans play more “authentic” jazz than white Americans. Even more surprisingly, Marsalis refused to allow black composer and educator George Russell to perform his latest work in the 1990s under the program’s auspices.

But there was another reason why Russell was denied performances of his music at Lincoln Center: this was the period when he was writing a lot of fusion pieces, and Marsalis hated fusion. I admit that I myself am antithetical towards the funky fusion of the 1970s and ‘80s, but I do like a certain amount of the earlier rock-jazz fusion played by such groups as The Electric Flag, the Ramsey Lewis Trio, and especially the amazingly complex music of the Don Ellis Orchestra (all those irregular time signatures!), but Marsalis hated it so that was that. As it turned out, however, he also hated all post-bop music: cool jazz (too white for him), third stream (he called it “classical music with a little bit of jazz in it” despite the work of such brilliant black composers in that field as Russell, Charles Mingus, J.J. Johnson. John Lewis and Wadada Leo Smith), free jazz (there went Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Pharaoh Sanders and the Art Ensemble of Chicago) and in fact anything modern that just didn’t strike his fancy.

Yet what galled most people about Marsalis was the fact that, although he was a good trumpet technician, his solos were never very interesting. Indeed, his lack of musical imagination has been criticized by both black and white trumpeters such as Lester Bowie and Jack Walrath. His three-record set The Majesty of the Blues, despite major hype from Columbia Records, simply died in sales because no one outside of his circle liked it, and although he gave himself commissions to write extended jazz works, none of them have ever really been very good. My old pen-pal from Nazare, Portugal, the late jazz and show music composer Alonzo Levister, once wrote me that my low assessment of Marsalis’ ballet music Jazz: Six Syncopated Movements was far too kind. He quite bluntly rated it as “garbage.” (For those who aren’t familiar with him, Levister was a black composer who had studied with Nadia Boulanger. He wrote the piece Slow Dance which was recorded by John Coltrane as well as a brilliant but forgotten third stream suite called Manhattan Monodrama.)

Still, the question remains: is jazz so much the creation of black musicians that we should not consider white jazz music or musicians to be valid? And were there no important innovations in jazz to be ascribed to white practitioners?

Reaching out to one of the modern-day black musicians I admire most, Arúan Ortiz, I received the following answer which I believe is typical of most serious jazz musicians:

I select musicians based on my knowledge of their playing and the needs of the project. All the musicians she mentioned, Bill Evans, Lennie Tristano and so on, were serious musicians, their body of work has been very influential in my career, and their contribution to this art form has been highly praised and appreciated for many generations of musicians (like me) over the years.

And the outstanding young black jazz trumpeter Jason Palmer also chimed in on this topic, saying

I believe this music is for everyone, and anyone who makes a contribution to it is providing something of value!

One of the most courageous and outspoken critics of the Crouch-Marsalis agenda has been the brilliant avant-garde pianist Matthew Shipp. Even back when Crouch was still alive, Shipp got into knock-down shouting matches with him, accusing him of trying to stunt modern forms of jazz. But to his credit, Shipp was not the one who initiated these conflicts. As he told Tad Hendrickson of All About Jazz in 2010, “I don’t initiate stuff, He’s always the one that starts it. If I am as not important as he says I am, why does he have such a problem with me?”[1]

And in an online interview with Dave Reitzes, I think Shipp hit the nail squarely on the head regarding Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center program:

…to use a position of privilege and money and power that’s based in conservatism, to denigrate other people’s efforts, is evil. I mean, that’s evil…And that’s where they’ve gone with the Lincoln Center.[2]

So there you have it, neatly summed up in a nutshell. Despite its avant-garde arts underground, New York City had always been an ultra-conservative, reactionary city that detests anything new and tries to crush it when it arises. They always point the finger at Boston, but at least in the 20th and 21st centuries, Boston was and continues to be at least with the times if not ahead of them. The money-that-talks in New York has always been reactionary in both the jazz and classical worlds. Composers and performers with modern ideas always have to turn to the smaller, less monied venues in order to find work and thrive. (Remember that we’re talking about a city whose main symphony orchestra castigated conductor Alan Gilbert for performing the complete symphonies of Carl Nielsen, a composer who died in 1931, in the 2010s!)

In a personal email to me, Shipp elaborated his position on these issues:

When I called the Lincoln Center evil in this interview, what I meant and what I was referring to was a personal conversation I had with Stanley Crouch where he told me he was superior to me because he made more money then me and I was still stuck in the lower East Side of Manhattan. It was a commentary on Crouch’s denigrating ad bullying ways with me personally. At the rime I took what Crouch said to me to be the agenda of jazz at Lincoln Center. In hindsight, I’ve gotten to know many people who work there who are great, decent people, and I’ve come to figure out they don’t have the same views as Crouch. I don’t know to what degree he dictated the agenda .

In my opinion, the main problem with Wynton was what seemed to me to be an attempt to be a spokesman for what jazz is. He always seemed to me to be trying to define what the music is. The universe can have a strange way of confounding you when you think you have a handle on the definition of something –the universe can serve up something contrary to your point of view that gains currency . At that point if you hold on to your definition you can come off as looking lost. That is the image my subconscious mind throws up to my conscious mind whenever I hear Wynton’s name. Yes, my opinion is that he is lost.

And he added a statement about mixed-race bands, which seems to be the universal view:

A person’s race never becomes a focal point when playing music to me. All the counts is the talent-the drive to play the music — whether we get along and enjoy each others company–and the compatibility of our musical language. . I cannot conceive of a world where your race enters as a factor about whether we play music together. The music decides who is to be joined together.

I personally recall hearing and reading statements from Marsalis, back in the 1990s, that he wanted to turn the clock back on jazz to the end of the bebop era and try to create his own evolution from that point forward…a fool’s errand which was never going to work because that horse left the barn too many years ago.

And of course, Wynton Marsalis and Stanley Crouch were scarcely the first to try to stop jazz evolution. Probably the first was William Russell, a modernist classical composer, who gradually convinced himself that the infinite rhythmic subtleties of the early New Orleans style were unique and, in fact, of paramount importance. The result was that Russell not only cut out all jazz that had evolved since Louis Armstrong, who he viewed as a bad influence rather than a much-needed innovator, but also contemporary 1920s jazz recordings made by whites, which he denigrated as “junk.” Then there was French critic Hughes Panassié, who came to America for the express purpose of convincing some record label (it turned out to be RCA Victor) to let him make records of small-group jazz featuring James P. Johnson on piano and Tommy Ladnier in trumpet, trying to show America that they should stop listening to the big swing bands, even the great ones, and go back to small-group improvisation. (But when jazz did go back to small group improvisation in the bop era, Panassié rejected it because his friend Charles Delaunay discovered it first!) And then, of course, there was the musical “war” between the trad jazz musicians, spearheaded by guitarist Eddie Condon, and the boppers in the late 1940s.

And let’s not even start on British jazz musicians, who for the most part are still living in the past. Sometimes this is with good effect. Such musicians as Keith Nichols, Andrew Oliver and Enrico Tomassi have given us impeccable and splendid recreations of some of the more innovative and interesting jazz musicians of the 1920s (King Oliver, Morton, Armstrong and arrangers Don Redman, Bill Challis and Tom Satterfield), but it’s sad to consider how few of them have followed in the footsteps of John Dankworth, Ronnie Scott or Tubby Hayes (who was sort of the British Charlie Parker). The majority are still playing the stiff Dixieland style pioneered by trombonist Chris Barber back in the early 1950s.

It’s rather ironic that saxophonist Charles Lloyd, an outstanding and highly original musician who came to prominence in the 1960s, would be a focal point both in his own time and much later on. In the mid-1960s, Lloyd was fawned over and lionized by Europeans and Russians, and even had a surprise success at Bill Graham’s Fillmore West Auditorium, normally the home of Hippie psychedelic rock bands, even though Lloyd did not play fusion at that time. By the late 1960s, however, his star enigmatically fizzled out simply because he didn’t play as much “outside” jazz as Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane or Eric Dolphy. Marsalis helped revive interest in him, decades later, by presenting him in concert at Lincoln Center—a rare instance of the program displaying the talents of a truly unique and fairly modern creator. But the irony here was that he was presented, pretty much, not as a vital creator still in his prime but as an example of a “right turn” in jazz that Marsalis approved of…which didn’t help his status in the jazz community.

Thus the majority of the jazz world has simply gone about its business, playing in all-black, all-white or mixed bands as the spirit moves them. Yet there is still a virulent anti-white and, as a sidelight, anti-formal music attitude among some writers on jazz, nowadays including white writers. One need look no further than Thomas Brothers’ 2006 book, Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans, where he goes even one step further than Marsalis, denigrating the contributions of Creoles of color and completely ignoring the contributions of whites (primarily the members of Jack “Papa” Laine’s various bands). Not even a jazz genius like Jelly Roll Morton, who even Marsalis likes, escaped Brothers’ sneering opinions. The argument that both Brothers and Marsalis make is that white music never influenced the course of jazz, and not just the classical composers. Marsalis went even further than Brothers in claiming that Jazz was not popular music—”it was not evolved as dance music”—a blatantly false and ignorant statement that omits not only the dance halls in New Orleans (and elsewhere) where jazz was played but also the Second Lines that trailed the mobile jazz bands as they marched and played in the streets.

Regarding Morton, he was, and remains, a controversial figure because of his claim that he invented jazz, but it is instructive to note that he didn’t claim to have invented improvised music. On the contrary, he freely admitted hearing, when growing up in New Orleans, the various “spasm” bands in which poor blacks played whatever instruments they could find or invent, including comb-and-tissue-paper, kazoos, and cheap horns sold at the Kress stores in the area. Morton also did not claim to have invented blue or slurred notes. We tend to forget that, although he always called him a ragtime player, we would have absolutely no idea how Buddy Bolden played were it not for Morton’s song, I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say. Its slow blues melody, which includes blue notes even when sung, is undoubtedly the closest we’ll ever get to what that cornet legend sounded like. Morton also noted that, ragtime player or not, Bolden had an extraordinarily powerful sound and was the king of using mutes to produce a “dirty” tone on his horn, a technique that was also adopted and brought to a fine art by Joseph “King” Oliver, and Morton admired Oliver enough to have recorded two of his songs, Chimes Blues and Doctor Jazz, recorded two songs with him, Tom Cat Blues and King Porter Stomp, and wrote a piece dedicated to him, Mister Joe (later renamed Buffalo Blues), despite the fact that he jokingly nicknamed him “Blondie” because he was so dark-skinned. But “Blondie” wasn’t meant as an insult, just as a joke.

I can’t recall reading anywhere what Morton really meant when he said that he invented jazz, thus I will spell it out for you here. What he meant was that he invented a music based on classic ragtime, which in turn was based on classical music, using an A-B-A-C structure, varying themes which would be played straight the first time through but altered the second or third time; that these pieces would include improvised “breaks” and full solo choruses for the musician to show his or her skills at creating an entirely new tune over the chords of the written chorus; and yet, in keeping with all New Orleans music, always “keeping the melody going,” even if just in the background. In addition to using ragtime as a basis, Morton also borrowed many ideas from formal classical music, of which he heard—as did all the early jazz musicians—around him in New Orleans. You simply couldn’t escape its influence. Perhaps the two most obvious examples in Morton’s oeuvre of this principle are The Pearls, in which all of the strains have a semi-classical quality, and Sidewalk Blues, the third strain of which, played by a clarinet trio, sounds so much like classical music that, the first time I heard it, I started scratching my brain trying to recall where I had heard it before. (But I hadn’t; it was entirely original.)

More importantly, Morton was the first jazz musician to be able to properly notate jazz phrasing, including the slurs, blue notes and breaks. Often, during the years in which he recorded with the Red Hot Peppers, he would say to musicians new to his style, “You’ll please me if you just play those little black dots.” It was all there in the music. One of the most interesting of his pieces was one he called Red Hot Pepper—Stomp in which the last strain begins as a trumpet solo. It is melodic and played with some jazz heat, but it isn’t really “jazzy.” But then, the trumpet section plays it, in what is clearly a written-out passage, and it is this ensemble that is a jazz variation on the theme the solo trumpet had played. I can’t recall any other jazz composer pulling off such a stunt in the entire history of the music.

Among the many innovations that white musicians brought to jazz and/or dance music, Lees brought up one I hadn’t known about, that it was Ferde Grofé, back in 1916 with the Art Hickman orchestra, who invented the saxophone section as we know it as well as the call-and-response between saxes and trumpets—and Lees has proof to back up his claim. True, the Hickman band didn’t use these devices in a true jazz manner—that was left to Don Redman (for the Fletcher Henderson orchestra) and Bill Challis (for the Jean Goldkette band)—but the fact that one could buy blank pages of sheet music with the saxophones lined up as we know them as far back as 1920-21 was Grofé’s legacy. And then, of course, there was C-melody saxist Frank Trumbauer (who was part American Indian) who, along with his amanuensis Bix Beiderbecke, influenced both Lester Young and Johnny Hodges, and Bix himself influenced an extraordinary number of musicians playing all sorts of instruments from trumpet to clarinet and xylophone (including Young and Rex Stewart). And it surely wasn’t because the “white press” touted Beiderbecke over Louis Armstrong. On the contrary, Armstrong was already becoming nationally famous by the time Beiderbecke died in 1931, while Bix himself never made a splash in the press until the Swing Era arrived in 1936-37 and many of the musicians who hit the big time started talking about him.

Lees points out that the prominence the Hickman band placed on saxophones was one reason why clarinetist Sidney Bechet began playing soprano sax about that time, and he was clearly the first great saxophonist in jazz. Coleman Hawkins was the first great tenor saxophonist in jazz, and everyone acknowledged it. Harry Carney was the first great baritone saxophonist, but probably because he was a member of Duke Ellington’s orchestra and didn’t solo all that often, his contribution was overlooked for decades. But the first great alto saxist in jazz, Jack Pettis, happened to be white, as was the only truly great bass saxophonist in jazz, Adrian Rollini. Everyone except the reverse racists acknowledge that Miff Mole was the first trombonist to treat the instrument as a fluent and legitimate jazz soloist, followed in turn by Jack Teagarden (white) and Jimmy Harrison (black). Joe Venuti was the first great jazz violinist, his musical partner Eddie Lang the pioneer of the jazz guitar. (There were some outstanding black blues guitarists like Lonnie Johnson and Blind Blake, but they rarely played jazz and never with a jazz orchestra as Lang did.) There were others later on, of course, but these were the important pioneers. Louis Armstrong often claimed that Vic Berton was the greatest jazz drummer in the world, at least during the 1920s, but his move to Hollywood in 1930 to try to break into the film industry removed him from the jazz scene, and by the time he returned to New York in 1935 he had been forgotten and his complex style of drumming, which included tuned tympani, considered too fussy for the Swing Era.

But most musicians who really understand jazz history know that, as Morton pointed out, it was the fusion of black soul and drive with the formal music education of Creoles and whites that led to jazz proper. Even those many jazz musicians who couldn’t or wouldn’t learn to read music (and, contrary to popular belief, King Oliver could read music, just very slowly) absorbed this influence by ear. Armstrong’s greatest influence, as Brothers rightly pointed out in his book, was his second wife, pianist Lil Hardin, who had studied classical music in college before joining King Oliver’s band and meeting her future husband. It was Lil who fully educated Louis in the harmonic changes and melodic niceties of classical music and showed him how to incorporate it into jazz. When they were married, they spent many an evening on their porch or patio working on tunes together, with Lil helping to formulate Louis’ ideas into coherent melodic lines that made musical sense.

As for the white “exploitation” of black musicians, this seldom happened within the jazz world. Blacks and whites learned from and fed off each other constantly, always with good results. Nor were the best white jazz promoters guilty of using or mistreating their black clients. Joe Glaser turned Armstrong from a frightened young man who was trying to escape the influence of the Chicago Mafia into a worldwide celebrity within two years, and he also did a world of good for his other clients, among them Roy Eldridge and Mary Lou Williams (to whom he even lent large sums of money when she was down and out). It should also be mentioned that Glaser took beatings from mob figures in the music industry for Louis. While it is true that Irving Mills demanded 50% of Duke Ellington’s salary as his client, he used that money to pay for luxurious band uniforms, new instruments when they needed them, first-class accommodations when they traveled abroad, and private railway cars so that they could tour the U.S. in style, unmolested by racist whites. Moreover, he demanded 50% of all of his clients, even when it was a single person like singer-songwriter Hoagy Carmichael, who quit Mills around 1935…but by that time, he had taken this Indiana hayseed with the quirky voice and made him a major star.

The real villains in the promotion of white musicians over black ones were not the independent promoters but the big booking agencies like MCA; the movie theater owners who refused to may most black bands the same money as whites or promote them as well (the two exceptions being Mills clients Ellington and Cab Calloway), and the mainstream press as opposed to the jazz press. They were the ones who dubbed Benny Goodman the “King of Swing,” an honor he did not lobby for, and once crowned they had no one else to take his place, but once the Count Basie band hit the scene in 1937, every jazz musician and critic recognized them as the swingingest band in the land. (Even Glenn Miller admired them so much that he was always trying to get a Count Basie vibe in his own band.) White bandleaders who had black musicians in their orchestras fought tooth and nail to get them the same respect and accommodations when they played down South as their white members. And everyone recognized the real geniuses of the music, for the most part, as being the black musicians.

Where black musicians have a legitimate gripe is that, despite the free-and-easy exchange of ideas and mixed-race recordings during the Swing Era, the social integration that this musical fusion seemed to forebode never came about. But again, it was the fault of the mainstream media and the booking agents, who simply would not promote any mixed bands in large venues. And once the swing era died in the late 1940s, jazz began to splinter into factions: the swing holdovers, the boppers, the new cool school spearheaded by Miles Davis and Lennie Tristano (who, by the way, made the first free jazz recordings in 1949!), and then the musical polarity of the hard bop musicians vs. the West Coast cool…and then the emergence of Third Stream. And the problem wasn’t just among the musicians who played these different styles, many of whom would cross over (late-bop trumpeter Clifford Brown recorded with West Coast cool musicians, and Charlie Parker even made a tour with Stan Kenton!), but among the fans of these various schools, who often disliked the opposing styles. Jazz clubs began going crazy trying to satisfy the audiences of all kinds of jazz by booking different groups at different times, but musical tastes were often dictated by geographical location, so it wasn’t so much a race war within the jazz world as simply a style war.

There was a reason for this. All the great arrangers in jazz, among them Fletcher Henderson, Redman, Challis, Benny Carter, Jimmy Mundy, Eddie Sauter, Gil Fuller, Tadd Dameron, George Handy, John Lewis, Quincy Jones and Gil Evans, had a working knowledge of classical music, and most of the best soloists had a working knowledge of music theory. This didn’t just drop on their heads from the sky. It was acquired knowledge. So to say that jazz has always been an instinctive music created by blacks in a musical vacuum from their racial heritage in the “African diaspora” is just blowing smoke.

And, as I said, the working interaction between black and white musicians was always a cordial one and a two-way street. Armstrong’s favorite trombonist was Teagarden. Charlie Parker’s favorite pianist was Al Haig and his favorite drummer was Buddy Rich. Art Tatum’s two main influences were Fats Waller, who also had a thorough grounding in the classics, and a white non-jazz pianist named Lee Sims, whose playing was nearly as ornate as that of Josef Hoffman. Benny Goodman’s favorite tenor saxists were Lester Young and Wardell Gray.

We thus need to look at the long and rich history of the music on both sides of the color line—and, perhaps more importantly, recognize the contributions of other “American” ethnicities, particularly that of Native Americans and Hispanics. Was the Latin influence in jazz a mistake, as Wynton Marsalis seems to think, or a revitalizing force? And what difference does it really make who was first to incorporate the wilder jazz rhythms into jazz, Dizzy Gillespie or Stan Kenton? Of course, different groups of musicians both white and black have their own styles and their own preferences, but aside from Armstrong and Parker I’d have to say that the most far-reaching influence on musicians of any color were Beiderbecke and Bill Evans. You simply cannot escape the influence of those four specific musicians; it is everywhere, and those who are honest will admit it.

Nineteen years before Lees’ book came out, Leonard Feather—another “good guy” in the fight for racial equality in jazz—brought up the “jazz by blacks only” issue, which was just starting at that time. He rightly attributed it, as Herbie Hancock did, as a backlash to so many decades of black musicians having their accomplishments minimized by the mainstream media, but added some important caveats to this movement:

Race issues aside, there remains the problem if whether today’s youth can relate to jazz as readily as to rock, provided they are given an extensive opportunity to hear it…jazz remains a music of minority appeal as it has always been. Even at the peak of the swing era, the Guy Lombardos and Kate Smiths were for the most part outselling Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw…Despite the upsurge in jazz clubs, the great advances at the academic level, the flood of records, an inescapable fact holds true: jazz is responsible for about two percent of all LP sales while rock accounts for approximately sixty-six percent.[3]

In fact, the jazz-for-blacks-only agenda went even further back than that. In a 1971 interview with vibraphonist Terry Gibbs, the latter is quoted as saying

My idols were men like Louis Armstrong, Duke, Benny Goodman, Dizzy, Charlie Parker—I guess about 90% of them were black, (Ibid, p. 161)

But it did him no good. He had severe trouble finding work…until the mid-1970s, when the college jazz programs began to proliferate, thanks mainly to people like Stan Kenton (who also had black musicians in his bands, like Karl George and Curtis Counce), and he began finding work again. Just not much in the jazz clubs.

And it wasn’t just white listeners who gravitated to “sweet” music. As Stephanie Stein Crease pointed out in her recent biography of Chick Webb, much to her horror and confusion, the band that drew the biggest crowds at the Savoy Ballroom and Apollo Theater was that of…Guy Lombardo!

Last but not least, think of this: Even at the time when Lees’ book was published, the venues for performing jazz had already shrunk beyond recognition to those who grew up in the 1940 and ‘50s. What had once been a thriving if minority industry had dried up considerably, the reason being that once jazz left popular music behind the fans of popular music—which included the majority of black listeners—simply turned their backs on it. And not only have things gotten worse in the past 28 years, but the number of hopeful and hungry young musicians graduating from all sorts of jazz education venues around the country want to have somewhere to play. Small wonder that you hear many new CDs by musicians you’ve never heard of before who will knock your ears out. But often, the record is the one place they can play—unless they’re willing, as Dave Brubeck was, to play weddings, graduation parties and bar mitzvahs. Heck, if Charlie Parker could do so (and he did), don’t feel too proud about it!

So if there are black musicians out there who still feel they have to monopolize jazz, I say to you, take a chill pill and just play your music. It will live or die based on its quality and how many people like it, not on the color of your skin. Amiri Baraka and Stanley Crouch are now long gone. Let’s inter Wynton in his little Lincoln Center tomb and get on with it. As Lees said, jazz was your gift to the world, so let the world participate and not just watch from the sidelines.

—© 2023 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter or Facebook

Check out the books on my blog…they’re worth reading, trust me!

[1] https://www.allaboutjazz.com/news/is-avant-jazz-pianist-matthew-shipp-his-own-worst-enemy/

[2] http://www.furious.com/perfect/matthewshipp4.html

[3] The Pleasures of Jazz by Leonard Feather, Dell Publishing Co., 1976, pp. 34-35.

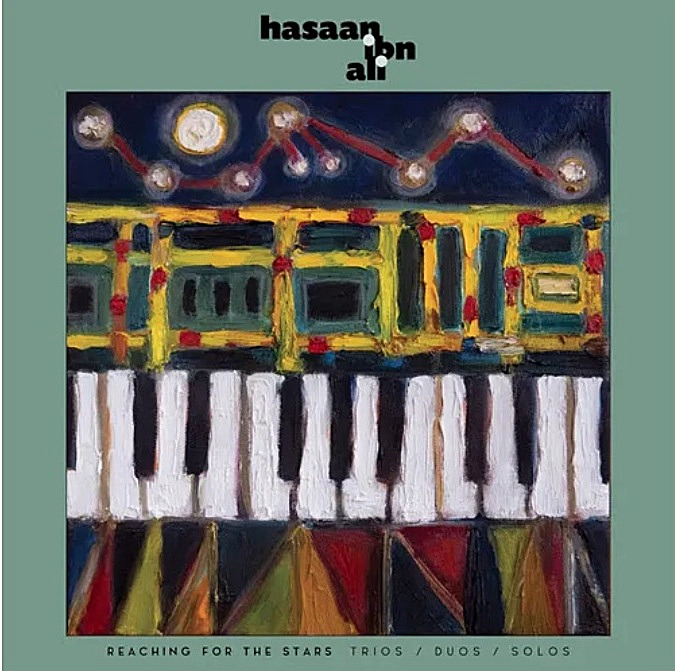

The resulting album, The Max Roach Trio Featuring the Legendary HASAAN, didn’t sell very well. Most jazz critics were utterly baffled by his playing style. But it did sell enough to make a profit, so Ertegun invited him back the next year to make a follow-up album with tenor saxist Odean Pope, also from Philadelphia, who claimed to be the only horn player who could keep up with him. Just before the album was due to be released, however, Ibn Ali was arrested on drug possession charges, so Ertegun shelved the tapes. They were lost in a huge warehouse fire in 1978 along with many others.

The resulting album, The Max Roach Trio Featuring the Legendary HASAAN, didn’t sell very well. Most jazz critics were utterly baffled by his playing style. But it did sell enough to make a profit, so Ertegun invited him back the next year to make a follow-up album with tenor saxist Odean Pope, also from Philadelphia, who claimed to be the only horn player who could keep up with him. Just before the album was due to be released, however, Ibn Ali was arrested on drug possession charges, so Ertegun shelved the tapes. They were lost in a huge warehouse fire in 1978 along with many others. Jazz critic Kenny Mathieson described Ibn Ali as having “a rhythmic quirkiness that had him compared with Monk and [Herbie] Nichols.” Wikipedia explains that “Ibn Ali examined the possibilities of playing fourths, and of using ‘chord progressions that moved by seconds or thirds instead of fifths, in playing a variety of scales and arpeggios against each chord’ – features later used extensively in Coltrane’s playing.” Drummer Sherman Ferguson described him as “a prime example of somebody that was very avant-garde in some ways, but he was always musical…[He] had this thing, where he had a natural feeling. He got to the thing where it swung no matter what he was doing.” Ibn Ali is also mentioned in avant-garde pianist Matthew Shipp’s article, Black Mystery School Pianists, which I recommend as an interesting take on some unusual keyboard artists (you can access it

Jazz critic Kenny Mathieson described Ibn Ali as having “a rhythmic quirkiness that had him compared with Monk and [Herbie] Nichols.” Wikipedia explains that “Ibn Ali examined the possibilities of playing fourths, and of using ‘chord progressions that moved by seconds or thirds instead of fifths, in playing a variety of scales and arpeggios against each chord’ – features later used extensively in Coltrane’s playing.” Drummer Sherman Ferguson described him as “a prime example of somebody that was very avant-garde in some ways, but he was always musical…[He] had this thing, where he had a natural feeling. He got to the thing where it swung no matter what he was doing.” Ibn Ali is also mentioned in avant-garde pianist Matthew Shipp’s article, Black Mystery School Pianists, which I recommend as an interesting take on some unusual keyboard artists (you can access it

EROS / BRIDGE: Phantasie Trio in c min. GRIME: 3 Whistler Miniatures. ERÖD: Piano Trio No. 1. GINASTERA: Danzas argentinas, No. 2: Danza de la moza donosa / Mithras Trio: Ionel Manciu, vln; Leo Popplewell, cello; Dominic DeGavino, pno / Linn Records CRD 733.

EROS / BRIDGE: Phantasie Trio in c min. GRIME: 3 Whistler Miniatures. ERÖD: Piano Trio No. 1. GINASTERA: Danzas argentinas, No. 2: Danza de la moza donosa / Mithras Trio: Ionel Manciu, vln; Leo Popplewell, cello; Dominic DeGavino, pno / Linn Records CRD 733.