This is the story of one of America’s great swing orchestras that happened to also be an all-woman band and the very first racially integrated female band in America. They were called the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, or ISR for short.

Dr. Laurence Jones

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm were founded at the Piney Woods Country Life School in Mississippi for poor and African American children in 1937 by Dr. Laurence Clifton Jones (1882-1975), the school’s principal and founder, also the band’s first leader. Some of the children who played in the band were orphans. Many started at the school at 13, 14, and 15 years old with no musical background at all, yet learned to play instruments and to play jazz. In their early years they played festivals, parades, county fairs and concerts around the area. Miss Sims, one of the original trombonists, said in a 1980 Kansas City Women’s Jazz Festival interview that it was a lot of fun for them to play certain arrangements; for her, it was the hit tune Christopher Columbus, one of the first pieces they were taught, because she could really enjoy pushing out the trombone slide.

The original concept of the band, however, was not entirely altruistic. Dr. Jones knew that a well-trained orchestra of female jazz musicians would be a novelty as well as a career for them, thus he toured with them to help raise money for the school. His inspiration was the all-female orchestra led by the talented singer-dancer Ina Ray Hutton since 1934. (It might be noted that neither Hutton nor her band have really gotten their due in jazz history either, although a side-by-side comparison shows that they weren’t quite as good as jazz improvisers as the musicians of the ISR.) Jones’ sister was also a music teacher who, back around 1919, taught Coleman Hawkins how to play the tenor saxophone. It should not be assumed, however, that Laurence Jones “used” the women in this orchestra. His granddaughter one said that he and his wife Grace were always “very strategic” in the way he used musicians to help raise funds. Piney Woods had an all-male jazz orchestra as well (in fact, before the Sweethearts of Rhythm were founded), and the all-female Cotton Blossom Singers. Interestingly, Jones didn’t believe in “co-ed anything; the girls were in one section of the camp, and the boys were in another section of the camp, and only for a certain amount of minutes, not hours, a day were they allowed to even talk to each other.”

Interestingly, Jones named the band the “International” Sweethearts of Rhythm not because they had played or were known internationally, but because of the different nationalities of the young women in the group. “We had Indians, we had Mexicans, Puerto Rican and Chinese girls…Willie Mae Lee Wong and Helen Jones, Tiny Davis and myself were the nucleus of the Sweethearts of Rhythm,” one of the trombonists said in 1980. As the band’s book became more demanding and the need for good musicians grew, however, Jones began recruiting girls from outside the school to buttress their musicianship. “We had girls from just about every state in the Union,” one member recalled, “This was before we even had white girls. I mean, we had girls who looked white but they were not white. Ros [Cron, one of the reed players] was our first white girl.” Ros Cron herself recalled that when she was 16, prior to joining the ISR, she had sat in with Eddie Durham’s All-Girl Orchestra in the early 1940s at the Raymor Playmor Ballroom in Boston, “and that was really the first time I had known that girls really played horns and really, really played real music, and I was just so amazed and loved it from that moment on.” At the end of the night, Durham asked her if she would join the band, but she said she didn’t think so because she was still in high school and her parents wanted her to graduate. “But it was in my head,” she added. “I knew this was something I really wanted to do.” Nevertheless, she played in all-male bands around the Boston area, and as the war started and the men began being drafted, she gained more and more experience. When she graduated in 1943 she felt ready to start her career, so she went on the road with a white band, Ada Leonard and her All-Girl Orchestra. There’s a 1943 video clip of this band with Cron on saxophone (she even gets a solo) which you can view HERE.

Dr. Jones also founded the Swinging Rays of Rhythm, another all-female band, concurrent with the International Sweethearts in 1937. They were the Sweethearts’ “understudies,” led by saxophonist Lou Holloway, and played performances when the Sweethearts were forced to attend school because they had been missing too many classes. Eventually, the Swinging Rays became the ISR’s replacement at Piney Woods, being led by Consuela Carter, touring throughout the East to raise money for the school.

In 1941 several girls in the ISR fled the school’s bus when they found out that some of them would not graduate because they had been touring with the band instead of sitting in class. That was when they decided to turn professional, severing all ties with Piney Woods in April of that year. Shortly thereafter the band settled in Arlington, Virginia, where a wealthy Virginian provided support for them and acquired a non-Piney Woods

Vi Burnside soloing with the band in a 1944 short film.

drummer, Pauline Braddy, who had been taught drums by Big Sid Catlett and Jo Jones. Eddie Durham, who had been writing charts for the band when they were still associated with Piney Woods, was replaced by Jesse Stone in 1941 when Durham, inspired by them, started his own all-woman outfit that year, taking some of the original Sweethearts with him. Stone also brought some more polished professionals into the band to fill some gaps in their soloing prowess. His two most important contributions were Ernestine “Tiny” Davis on trumpet and tenor saxophonist Violet “Vi” Burnside (1915-1964) who had been working with the all-black Harlem Playgirls. Known as the “female Coleman Hawkins,” Burnside’s huge, commanding tone and excellent solos quickly became centerpieces of the band.

They also acquired their leader, the very pretty singer Anna Mae Winburn, in 1941. Winburn (1913-1999) had been performing with an all-male band, the Cotton Club Boys of North Omaha, Nebraska, which had once included Charlie Christian on guitar, until the band was “raided” by Fletcher Henderson. Winburn would remain the ISR’s leader and primary singer until they disbanded. Around 1943, Jesse Stone was replaced as the band’s principal writer and arranger by one Maurice King. King wrote some of the group’s most famous killer-diller swing tunes like Swing Shift, Vi Vigor, Slightly Frantic, Don’t Get it Twisted and She’s Crazy With the Heat as well as blues specialties for Winburn, That Man of Mine and I Left My Man.

They also acquired their leader, the very pretty singer Anna Mae Winburn, in 1941. Winburn (1913-1999) had been performing with an all-male band, the Cotton Club Boys of North Omaha, Nebraska, which had once included Charlie Christian on guitar, until the band was “raided” by Fletcher Henderson. Winburn would remain the ISR’s leader and primary singer until they disbanded. Around 1943, Jesse Stone was replaced as the band’s principal writer and arranger by one Maurice King. King wrote some of the group’s most famous killer-diller swing tunes like Swing Shift, Vi Vigor, Slightly Frantic, Don’t Get it Twisted and She’s Crazy With the Heat as well as blues specialties for Winburn, That Man of Mine and I Left My Man.

With all these elements now in place, the ISR really began to take off in popularity during 1943-44. They played the Apollo Theater in Harlem, the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C., the Regal Theater in Chicago, the Cotton Club in Cincinnati, the Riviera in St. Louis, the Dreamland in Omaha and the Club Plantation and Million Dollar Theater in Los Angeles, all venues that were geared primarily if not exclusively towards black audiences. Famous jazz critic Leonard Feather wrote in a Los Angeles Times article that “if you are white, whatever your age, chances are you have never heard of the Sweethearts[…].” Yet they swiftly rose to fame, as evidenced in one Howard Theater show when the band set a new box office record of 35,000 patrons in one week of 1941. After playing the Regal Theater in 1943, the Chicago Defender praised the band as “one of the hottest stage shows that ever raised the roof!” A great advantage to touring across the states was that, when in Hollywood, they were able to make short films to use as “fillers” in movie theaters.

Despite all of this, several impediments stood in their way of complete success, primarily opportunities for commercial recording. To the best of my online research, they seem to have only made four sides for the small Guild record label in May or June of 1945. Guild was the same label that the ill-fated Boyd Raeburn Orchestra started with, but Raeburn also made records for the equally small Jewell label while the ISR had no further opportunities. The bulk of the ISR’s legacy stems from broadcast transcripts of the Armed Forces Radio program “Jubilee,” hosted by the irritating, sycophantic but seemingly popular loudmouth Ernie “Bubbles” Whitman. As in Raeburn’s case, the dearth of commercial recordings eventually led to their undoing. Johnny Mercer, who sang one number with Freddie Slack’s band (Waitin’ for the Evening Mail) on their Jubilee broadcast of July 17, 1945, was so impressed by them that he tried to sign them to his Capitol Records label, but although he was one of Capitol’s founding members, by 1945 there was a Board of Directors in charge and they nixed the idea since, unlike Nat “King” Cole, the band’s strongest appeal was to African-American audiences only.

Despite all of this, several impediments stood in their way of complete success, primarily opportunities for commercial recording. To the best of my online research, they seem to have only made four sides for the small Guild record label in May or June of 1945. Guild was the same label that the ill-fated Boyd Raeburn Orchestra started with, but Raeburn also made records for the equally small Jewell label while the ISR had no further opportunities. The bulk of the ISR’s legacy stems from broadcast transcripts of the Armed Forces Radio program “Jubilee,” hosted by the irritating, sycophantic but seemingly popular loudmouth Ernie “Bubbles” Whitman. As in Raeburn’s case, the dearth of commercial recordings eventually led to their undoing. Johnny Mercer, who sang one number with Freddie Slack’s band (Waitin’ for the Evening Mail) on their Jubilee broadcast of July 17, 1945, was so impressed by them that he tried to sign them to his Capitol Records label, but although he was one of Capitol’s founding members, by 1945 there was a Board of Directors in charge and they nixed the idea since, unlike Nat “King” Cole, the band’s strongest appeal was to African-American audiences only.

But Mercer wasn’t the only one who failed to give the band a leg up. Most male jazz musicians, particularly black ones, were only too happy to see the band struggle because they represented a threat to them. In an interview taped in the 1990s, Anna Mae Winburn said that they were “women trying to make a place in the world among musicians where prejudice existed because they were women.”

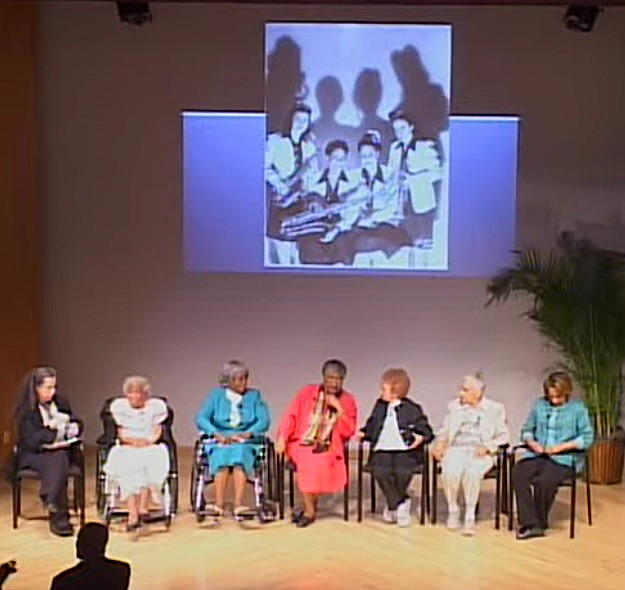

Surviving band members and Dr. Jones’ granddaughter (far right) being interviewed in 1980.

During interviews with other band members at the 1980 Kansas City Women’s Jazz Festival mentioned earlier, pianist Johnnie Mae Rice also brought up the fact that they “practically lived on the bus, using it for music rehearsals and regular school classes, arithmetic and everything.” Despite being stars throughout the country, when they played down South they also had to sleep and eat on the bus due to segregation. At the same Festival interview, Roz Cron complained that “We [the white members] were supposed to say ‘My mother was black and my father was white’ because that was the way it was in the South. Well, I swore to the Sheriff in El Paso that that’s what I was, but he went through my wallet and there was a photo of my mother and father sitting before our little house in New England with the picket fence, and it just didn’t jell. So I spent the night in jail.” Eventually, the white women in the band wore dark makeup on stage to avoid arrest. In addition, the band earned less in the South than in other venues. Saxist Willie Mae Wong, however, explained at the same Festival how they struggled financially throughout the country. “The original members received $1 a day for food plus $1 a week allowance, for a grand total of $8 a week,” she said. “That went on for years, until we got a substantial raise—to $15 a week. By the time we broke up, we were making $15 a night, three nights a week.” Yet in 1944, the band was named “America’s No. 1 All-Girl Orchestra” by down beat.

During World War II, letter-writing campaigns from overseas African American soldiers demanded them, and in 1945 the band embarked on a six-month European tour to France and Germany, making them the first black women to travel with the USO.

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm performed in 1948 alongside Dizzy Gillespie at the fourth annual Cavalcade of Jazz concert held at Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field on September 12. Also on the program that day were Frankie Laine, Jimmy Witherspoon, Joe Turner, The Honeydrippers, The Blenders and The Sensations. They also played at the eighth Cavalcade of Jazz concert at Wrigley Field on June 1, 1952. Other featured artists were Jerry Wallace, Roy Brown and His Mighty Men, Louis Jordan, Witherspoon and Josephine Baker. According to Wikipedia,

A great number of reasons, both known and purported, have been doled out as to why the International Sweethearts of Rhythm began their gradual disbandment after they returned from their European tour in 1946: marriage, career change, tiring of always being on the road, aging, not enough money for all the effort, managerial issues, deaths in the group, etc. Tiny Davis had to turn down the opportunity to tour again with the band in 1946. Mrs. Rae Lee Jones continued to fight for the life of the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, but after 1946, the key instrumentalists had already left the group, leaving the band to unravel and unfold finally with Mrs. Jones’s passing away in 1949.

By the late 1940s, too, there were a few other competing all-women swing bands, among them the Darlings of Rhythm, to which some of the ISR members jumped. In addition, as guitarist Carline Ray Russell admired, “the musical tides were changing” away from big bands to smaller ones and away from swing to bebop. In that atmosphere, the ISR were a musical anachronism. Thus they faded from the scene after 1952.

It’s difficult to say whether the International Sweethearts of Rhythm can be called a “forgotten” jazz orchestra because, to a large extent, most of America was pretty much unaware of them in the first place. Without recordings to go by, it’s even harder to tell if Eddie Durham’s all-girl orchestra, the Darlings or Rhythm or other competitors were just as good or better, but there’s no question that the ISR were trailblazers who had more of an impact on black audiences of their time than any other all-woman big band. Although their arrangements were very good, they were not stylistically unique or harmonically interesting. Their principal assets were their astonishing ensemble esprit de corps and the top-notch quality of their solos, which can be heard in any of their surviving recordings or film clips, nearly all of them from 1944-46 when they were at the top of their game. Yet they clearly remain an archetype, a matrix for all-woman jazz orchestras everywhere. Musically speaking, they were in the right place at the right time, but socially speaking they were out of synch with America in the 1940s. Had they reached their peak in the late 1960s, after most of the Civil Rights battles had been won for African-Americans and women’s rights were also on the rise, they would surely have fared better. And at least we can still listen to or watch them and enjoy their energy and talent.

It’s difficult to say whether the International Sweethearts of Rhythm can be called a “forgotten” jazz orchestra because, to a large extent, most of America was pretty much unaware of them in the first place. Without recordings to go by, it’s even harder to tell if Eddie Durham’s all-girl orchestra, the Darlings or Rhythm or other competitors were just as good or better, but there’s no question that the ISR were trailblazers who had more of an impact on black audiences of their time than any other all-woman big band. Although their arrangements were very good, they were not stylistically unique or harmonically interesting. Their principal assets were their astonishing ensemble esprit de corps and the top-notch quality of their solos, which can be heard in any of their surviving recordings or film clips, nearly all of them from 1944-46 when they were at the top of their game. Yet they clearly remain an archetype, a matrix for all-woman jazz orchestras everywhere. Musically speaking, they were in the right place at the right time, but socially speaking they were out of synch with America in the 1940s. Had they reached their peak in the late 1960s, after most of the Civil Rights battles had been won for African-Americans and women’s rights were also on the rise, they would surely have fared better. And at least we can still listen to or watch them and enjoy their energy and talent.

—© 2019 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter (@artmusiclounge) or Facebook (as Monique Musique)

Read my book, From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed guide to the intersection of classical music and jazz

My first experience with him came in 1968, a year after I discovered Fritz Wunderlich via recordings—a Mozart aria recital on Decca-London, conducted by Otmar Suitner. For those who have never heard this album, I urge you to do so. At age 33, he was already an intelligent, musical and interesting singer, and the voice had not yet picked up that slightly dry, “sandpapery” quality that came into his voice two years later and stayed there for the rest of his life. In fact, I would go do far as to say that in its own way his voice on this recital was nearly as beautiful as Wunderlich’s. I thought so in 1968 and I still think so now in re-listening to it. Moreover, the repertoire on his follow-up Mozart LP was quite unusual for its time, including arias from La clemenza di Tito, La finta giardiniera, Lucio Silla, Il re pastore and Idomeneo, all operas I hadn’t heard by then, including the most technically difficult of all Mozart tenor arias, “Fuor del mar” from Idomeneo (including the trill). I was convinced immediately that we had a new major light tenor star in our midst—and I was not mistaken.

My first experience with him came in 1968, a year after I discovered Fritz Wunderlich via recordings—a Mozart aria recital on Decca-London, conducted by Otmar Suitner. For those who have never heard this album, I urge you to do so. At age 33, he was already an intelligent, musical and interesting singer, and the voice had not yet picked up that slightly dry, “sandpapery” quality that came into his voice two years later and stayed there for the rest of his life. In fact, I would go do far as to say that in its own way his voice on this recital was nearly as beautiful as Wunderlich’s. I thought so in 1968 and I still think so now in re-listening to it. Moreover, the repertoire on his follow-up Mozart LP was quite unusual for its time, including arias from La clemenza di Tito, La finta giardiniera, Lucio Silla, Il re pastore and Idomeneo, all operas I hadn’t heard by then, including the most technically difficult of all Mozart tenor arias, “Fuor del mar” from Idomeneo (including the trill). I was convinced immediately that we had a new major light tenor star in our midst—and I was not mistaken.

Playmates is a good example because the song itself was meant to be silly. It was written by jazz bandleader Saxie Dowell—or at least the lyrics were. The melody was stolen note-for-note from the second strain of a 1904 ragtime piece called Iola by one Charles L. Johnson, who sued Dowell for plagiarism. Johnson settled out of court for an undisclosed sum but was financially independent for the rest of his life. (In case you’re interested, Johnson also wrote such deathless tunes as the Hen Cackle Rag and Pansy Blossoms, neither of which anyone bothered to borrow.) The beat underlying the vocals by Sully Mason and, later, “Audrey and her Playmates,” actually Harry Babbitt singing in falsetto with Ginny Simms while Mason sings jug-band-style bass notes, is purposely played stiffly in a ragtime manner; in addition, “Audrey” and her friends sing the last note of each four-bar phrase flat. But the intro and outro, as well as the jazz clarinet and flute solos, are played with great heat and in these sections the band really swings. In short, the band is camping it up, which didn’t always occur in these novelty tunes but certainly occurred here.

Playmates is a good example because the song itself was meant to be silly. It was written by jazz bandleader Saxie Dowell—or at least the lyrics were. The melody was stolen note-for-note from the second strain of a 1904 ragtime piece called Iola by one Charles L. Johnson, who sued Dowell for plagiarism. Johnson settled out of court for an undisclosed sum but was financially independent for the rest of his life. (In case you’re interested, Johnson also wrote such deathless tunes as the Hen Cackle Rag and Pansy Blossoms, neither of which anyone bothered to borrow.) The beat underlying the vocals by Sully Mason and, later, “Audrey and her Playmates,” actually Harry Babbitt singing in falsetto with Ginny Simms while Mason sings jug-band-style bass notes, is purposely played stiffly in a ragtime manner; in addition, “Audrey” and her friends sing the last note of each four-bar phrase flat. But the intro and outro, as well as the jazz clarinet and flute solos, are played with great heat and in these sections the band really swings. In short, the band is camping it up, which didn’t always occur in these novelty tunes but certainly occurred here.

Listening to Gifford’s charts, even today, when stupendous technical proficiency is common place in jazz bands, leaves a stupefying impression. It wasn’t just the speed and dexterity of the musicians that impresses one, it’s also the way Gifford could play one rhythm against another, at some points juggling three contrasting rhythms at a time, and how he knit these disparate sections of the music together to make a whole piece. In the playlist below, I have concentrated on the high-fidelity remakes that Gray made in 1956 because the sound quality is far superior and gives you a much better idea of what the band actually sounded like in person, but I assure you that, for all their boxiness, you can hear exactly the same speed and precision on the original recordings. Indeed, the Casa Lomans required such impeccable chops from their players that when Bix Beiderbecke, impressed by what they had to offer, auditioned for the band in late 1930 he was turned down because he couldn’t play with such perfect precision.

Listening to Gifford’s charts, even today, when stupendous technical proficiency is common place in jazz bands, leaves a stupefying impression. It wasn’t just the speed and dexterity of the musicians that impresses one, it’s also the way Gifford could play one rhythm against another, at some points juggling three contrasting rhythms at a time, and how he knit these disparate sections of the music together to make a whole piece. In the playlist below, I have concentrated on the high-fidelity remakes that Gray made in 1956 because the sound quality is far superior and gives you a much better idea of what the band actually sounded like in person, but I assure you that, for all their boxiness, you can hear exactly the same speed and precision on the original recordings. Indeed, the Casa Lomans required such impeccable chops from their players that when Bix Beiderbecke, impressed by what they had to offer, auditioned for the band in late 1930 he was turned down because he couldn’t play with such perfect precision.

In addition to using studio musicians, Gray brought back two of his original musicians, Murray McEachern to play alto and tenor sax and Kenny Sargent to sing on For You (the underrated Shorty Sherock recreated Dunham’s trumpet solo on Memories of You), but they clearly played the old Gene Gifford scores note for note—Casa Loma Stomp, White Jazz, Black Jazz, Dance of the Lame Duck and Maniac’s Ball—plus the recreated No Name Jive that startled Capitol when the LP sold a half million copies. Gray was invited back the next year to record Casa Loma Caravan, which included Sargent’s vocal on Under a Blanket of Blue, but this was filled more with dreamy ballads. Undeterred, Capitol had enough faith in Gray’s musicianship to turn him loose on recreations of other bands’ hits, an LP called Sound of the Great Bands in 1957. Now in stereo, Gray hired top Hollywood jazz session players

In addition to using studio musicians, Gray brought back two of his original musicians, Murray McEachern to play alto and tenor sax and Kenny Sargent to sing on For You (the underrated Shorty Sherock recreated Dunham’s trumpet solo on Memories of You), but they clearly played the old Gene Gifford scores note for note—Casa Loma Stomp, White Jazz, Black Jazz, Dance of the Lame Duck and Maniac’s Ball—plus the recreated No Name Jive that startled Capitol when the LP sold a half million copies. Gray was invited back the next year to record Casa Loma Caravan, which included Sargent’s vocal on Under a Blanket of Blue, but this was filled more with dreamy ballads. Undeterred, Capitol had enough faith in Gray’s musicianship to turn him loose on recreations of other bands’ hits, an LP called Sound of the Great Bands in 1957. Now in stereo, Gray hired top Hollywood jazz session players  and gave note-for-note recreations of other bands’ hits such as Ellington’s Take the “A” Train, Jimmy Dorsey’s Contrasts, Woody Herman’s Woodchoppers Ball, Claude Thornhill’s Snowfall, Glenn Miller’s A String of Pearls, Lionel Hampton’s Flying Home and Bobby Sherwood’s The Elks Parade. This, too, was a major seller for the label, which led to Sounds of the Great Bands Vols. 2 & 3, Please Mr. Gray [By Request], Sounds of the Great Bands Vol. 4, They All Swung the Blues [Sounds of the Great Bands Vol. 5] and Themes of the Great Bands [Sounds of the Great Bands Vol. 6]. Gray was making a pretty penny off other bands’ material…and somehow, yet again, the Casa Loma sound faded from view even as the name was revived. His last album was Jonah Jones/Glen Gray, an album of all-new Basie-styled arrangements, although two more Sounds of the Great Bands LPs were issued posthumously, actually conducted by Larry Wagner and Van Alexander. Gray, whose health had been failing for the past five years, refused to reform a Casa Loma band for touring. He died on August 23, 1963.

and gave note-for-note recreations of other bands’ hits such as Ellington’s Take the “A” Train, Jimmy Dorsey’s Contrasts, Woody Herman’s Woodchoppers Ball, Claude Thornhill’s Snowfall, Glenn Miller’s A String of Pearls, Lionel Hampton’s Flying Home and Bobby Sherwood’s The Elks Parade. This, too, was a major seller for the label, which led to Sounds of the Great Bands Vols. 2 & 3, Please Mr. Gray [By Request], Sounds of the Great Bands Vol. 4, They All Swung the Blues [Sounds of the Great Bands Vol. 5] and Themes of the Great Bands [Sounds of the Great Bands Vol. 6]. Gray was making a pretty penny off other bands’ material…and somehow, yet again, the Casa Loma sound faded from view even as the name was revived. His last album was Jonah Jones/Glen Gray, an album of all-new Basie-styled arrangements, although two more Sounds of the Great Bands LPs were issued posthumously, actually conducted by Larry Wagner and Van Alexander. Gray, whose health had been failing for the past five years, refused to reform a Casa Loma band for touring. He died on August 23, 1963.

This concert, it seems, has been around for quite a while. It first popped up on vinyl in the early 1980s on Relief 822-2, then later on was issued on CD by Radio Years (99), Rare Toscanini (005) and the label pictured above, Originals (with no number). I just ran across it a few days ago on YouTube and have been listening in some amazement.

This concert, it seems, has been around for quite a while. It first popped up on vinyl in the early 1980s on Relief 822-2, then later on was issued on CD by Radio Years (99), Rare Toscanini (005) and the label pictured above, Originals (with no number). I just ran across it a few days ago on YouTube and have been listening in some amazement.