The title of this article may sound pretty anarchist; in fact, it may even sound as if I were encouraging an illegal activity. But in point of fact, as I shall point out in short order, what I am saying is that modern American copyright laws regarding sound recordings, and particularly recordings older than 50 years, are virtually null and void, and that this nullification of existing copyright law has been effected mostly by the very companies that own the rights.

But first, some background. Up until about a decade ago, the statute of limitations on the  copyright of ANY published work, whether in print media or recorded media, was 50 years. Period. End of sentence. No caveats, no further restrictions. But then poor little Naxos Records, which had been issuing historical classical recordings under its “Great Recordings of the Century” series for over a decade, started issuing the old mono opera recordings of Maria Callas.

copyright of ANY published work, whether in print media or recorded media, was 50 years. Period. End of sentence. No caveats, no further restrictions. But then poor little Naxos Records, which had been issuing historical classical recordings under its “Great Recordings of the Century” series for over a decade, started issuing the old mono opera recordings of Maria Callas.

EMI, which had made a bloody fortune off Callas’ recordings several times over (including a few times extra since her death), swung into action. You did NOT step on their biggest cash cow!!!

Somehow or other, EMI was unable to sway British or other European countries into extending the length of copyright time to protect them, but in America they found three willing allies to come to their aid. These were the Walt Disney empire, which suddenly realized that all of those classic songs and animated movies they had made prior to Walt’s death were suddenly about to be pilfered by nefarious people for ill-gotten gain; Sony-RCA, which suddenly noticed that this would affect their stash of Elvis Presley recordings; and Capitol Records, a division of EMI, which also came to realize that the advent of The Beatles 50 years earlier was on the horizon. Thus they managed to get the U.S. Congress—weasels all, and

Somehow or other, EMI was unable to sway British or other European countries into extending the length of copyright time to protect them, but in America they found three willing allies to come to their aid. These were the Walt Disney empire, which suddenly realized that all of those classic songs and animated movies they had made prior to Walt’s death were suddenly about to be pilfered by nefarious people for ill-gotten gain; Sony-RCA, which suddenly noticed that this would affect their stash of Elvis Presley recordings; and Capitol Records, a division of EMI, which also came to realize that the advent of The Beatles 50 years earlier was on the horizon. Thus they managed to get the U.S. Congress—weasels all, and  undoubtedly on the take from one or more of these organizations—to draw up one of the most binding, restrictive and far-reaching laws of all time, to wit, 95 years from the date of publication if copyright was renewed during the 28th year.

undoubtedly on the take from one or more of these organizations—to draw up one of the most binding, restrictive and far-reaching laws of all time, to wit, 95 years from the date of publication if copyright was renewed during the 28th year.

Incidentally—and I find this exceptionally interesting—sound recordings were originally NOT part of any copyright law in the United States. Did you know that? It’s true. Before 1972 recordings weren’t covered at all, which explains all those Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix bootleg albums that circulated in the late 1960s-early ‘70s. Yet although copyright was not extended to recordings, it was illegal to make copies of commercial recordings. Hmmm…what happened around 1972 that would have prompted such a move? Oh, yeah! It was the sudden proliferation of cassette tapes! Suddenly, people were taping their favorite LPs and even making free copies for their friends, thus eliminating said friends’ need to buy the LP.

In fact, that was the first really restrictive such law on records. The Sound Recording Amendment of 1971 extended federal copyright to recordings fixed on or after February 15, 1972, and declared that recordings fixed before that date would remain subject to state or common law copyright. Subsequent amendments have extended this latter provision until 2067, thus ensuring that some fat corporate pig who hasn’t even been born at this point will be ensured of sloughing off profits from records he doesn’t even yet know exist. Still, even now, all copyrightable works published in the United States before 1923 are in the public domain; works created before 1978 but not published until recently may be protected until 2047.

In fact, that was the first really restrictive such law on records. The Sound Recording Amendment of 1971 extended federal copyright to recordings fixed on or after February 15, 1972, and declared that recordings fixed before that date would remain subject to state or common law copyright. Subsequent amendments have extended this latter provision until 2067, thus ensuring that some fat corporate pig who hasn’t even been born at this point will be ensured of sloughing off profits from records he doesn’t even yet know exist. Still, even now, all copyrightable works published in the United States before 1923 are in the public domain; works created before 1978 but not published until recently may be protected until 2047.

Fun, huh? So if you’re into historic jazz and classical recordings, the only ones that are fair game no matter what are the acoustic things made with those morning glory horns that sound like people singing and playing into a tin funnel.

But somewhere along the way, something happened to completely screw up this wonderful scheme that the Disney-Callas-Elvis-Beatles Law cooked up. That something was the collapse of the commercial CD market. Oh, sure, a good 20% of the population—like me—are still buying CDs or burning them from the downloads we get to review for our own personal use, no copies made for anyone else. But 80% of music lovers, and this includes classical and jazz lovers, no longer bother with CDs at all. They store their music on iPods, iPhones, tablets, droids or jump sticks, and then play them through crappy-sounding ear buds or almost-as-crappy speakers. This has put a considerable crimp in the major record labels’—and the indies’—ability to persuade what’s left of the market to buy physical CDs. In short, the entire industry has bottomed out.

What to do, what to do? Well, I’ll tell you what they’ve done. In a cut-off-your-nose-to-spite-your-face move, the record labels—biggies and small ones, new releases and reissues—have put up audio files of complete works (symphonies, operas, concertos, chamber works etc.) on YouTube and Spotify for free streaming. But what this means is that anyone who has a computer with an audio editor downloaded to it, anything from Audacity (which is free and surprisingly powerful) to GoldWave or better systems, can record the streaming audio, make .wav files out of them, and burn them to a CD anytime they want.

Moreover, one of the industry giants, Sony Entertainment which owns the complete Sony Classical, former Columbia Masterworks and jazz series discs, and the entirety of the old RCA Victor catalog, has gone the others one step further. They have a service called Freegal, which stands for “free and legal,” which is leased through big city public libraries throughout the United States (and possibly in the UK and Australia for all I know). All you need to log in to Freegal is your library card number and a PIN. And once you’re logged in, nearly half of the world’s recordings are yours to take…for nothing. That’s right. Freegal allows users to download 7 tracks per week, to do whatever the hell you want to do with them, and unlimited free streaming. So if you’re a member of a household with two parents and two kids, and all of you have library cards, you could conceivably take turns logging in every week using your household’s card numbers and download 28 tracks. Every single week—no restrictions at all.

Moreover, as I indicated above, Freegal is not restricted to any genre or any particular era. I’ve seen a ton of modern, contemporary recordings offered there that I personally could care less about: Adele, Boyz 2 Men, The Piano Guys, and various rappers. I don’t even listen to them. But I’ve also found a treasure trove of things there, and as I say they’ve somehow gotten a ton of independent labels—the very people they passed their stupid law against—to allow their reissues of once-copyrighted material from RCA, Brunswick, OKeh, Pathé, Columbia, American Decca, Capitol and other labels to be downloaded and streamed free of charge. Lots of Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Art Tatum, Dorothy Donegan, Tiny Parham, Fats Waller, Horace Silver, Dave Brubeck, Clifford Brown, MJQ, you name it, they’re probably there. Freegal was where I went to find the out-of-print RCA recordings that the great cellist Emanuel Feuermann made with Jascha Heifetz, William Primrose and Arthur Rubinstein. They’re all there. So too are a bunch of Fritz Reiner, Charles Munch, George Szell and Herbert von Karajan recordings. I’ll bet you I’d find some of the modern-day people if I looked hard enough, too (I did find Wadada Leo Smith there). It’s like being a kid in a candy store on “Everything’s Free” day.

Ah, you say, but this would only benefit YOU personally, because we still have that 1972 law around that restricts copying and disseminating recorded material. Right?

Welllll…..as I’ve said, new innovations have led to new laws. In May of this year, 2016, Judge Percy Anderson ruled in a lawsuit between ABS Entertainment and CBS Radio that “remastered” versions of pre-1972 recordings can “receive a federal copyright as a distinct work [emphasis mine] due to the amount of creative effort expressed in the process.”

What does this mean? Why, that when a big label does a brand-new 24-bit high-definition mastering of, say, a 1962 stereo recording, and significantly changes the sound quality, it’s now suddenly a new recording. But with my audio editors, I can do the exact same thing myself with a 50-year-or-older recording, and guess what? I OWN THAT COPYRIGHT! And thus I can do anything with it that I damn well please, and the law can’t touch me! This, by the way, is also what protects such great independent classical labels as Pristine Classical, Guild, Immortal Performances, Nimbus, Marston and APR, which technically improve old studio and acetate recordings with new equalization, noise reduction and/or judicious amounts of reverb to enhance the original dead sound quality.

Thus the copyright law has finally come around full circle to bite the very corporations that enacted it in the first place in the behind. Not to mention that both the audio streaming websites (YouTube and Spotify) and Freegal, by their very nature, now VIOLATE one of the basic tenets of the law, which is “To digitally transmit sound recordings by means of digital audio transmission.”

The dog has not only chased its own tail; it has caught it, and is eating it.

And that is why I say unto thee, Go forth into the big, wide world, recognize the 50-year copyright if you want to be nice and fair, but do unto others as they are doing unto themselves and their artists. Namely, take what you can find for free and learn from it, study it, enjoy it, disseminate it.

And that wraps up my sermon for today: Take this music. Please.

—© 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Return to homepage OR

Read The Penguin’s Girlfriend’s Guide to Classical Music

was initially issued on RCA Victor with a shocking pink cover (see right), but it was pulled from the shelves by the time Björling died in 1960. A similar fate met the 1960 Leontyne Price-Björling-Fritz Reiner recording of the Verdi Requiem. It was issued in the U.S. on the RCA Victor “Soria Series,” yet was pulled from circulation by abount 1962 because by then the reciprocal agreement between RCA and Decca had expired. Yet, for some strange reason, the 1959 Turandot remained steadfastly on RCA Victor, despite the fact that they used not one but two of Decca’s hottest properties, Tebaldi and Birgit Nilsson. In the end, Decca definitely got the short end of the stick because the only recording Björling lived to complete (if you could call it “complete”) was a single operetta aria, “Dein ist mein ganzes Herz,” as an insert on the Herbert von Karajan “gala edition” of Johann Strauss’s Die Fledermaus. Björling was scheduled to record Un Ballo in Maschera at the Sofiensaal in Vienna with Tebaldi, Bastianini and Georg Solti, but except for a few incomplete run-throughs of snippets from the opera nothing exists on tape of him singing that opera. Björling died suddenly of a heart attack in September 1960 and was replaced in the recording by Carlo Bergonzi.

was initially issued on RCA Victor with a shocking pink cover (see right), but it was pulled from the shelves by the time Björling died in 1960. A similar fate met the 1960 Leontyne Price-Björling-Fritz Reiner recording of the Verdi Requiem. It was issued in the U.S. on the RCA Victor “Soria Series,” yet was pulled from circulation by abount 1962 because by then the reciprocal agreement between RCA and Decca had expired. Yet, for some strange reason, the 1959 Turandot remained steadfastly on RCA Victor, despite the fact that they used not one but two of Decca’s hottest properties, Tebaldi and Birgit Nilsson. In the end, Decca definitely got the short end of the stick because the only recording Björling lived to complete (if you could call it “complete”) was a single operetta aria, “Dein ist mein ganzes Herz,” as an insert on the Herbert von Karajan “gala edition” of Johann Strauss’s Die Fledermaus. Björling was scheduled to record Un Ballo in Maschera at the Sofiensaal in Vienna with Tebaldi, Bastianini and Georg Solti, but except for a few incomplete run-throughs of snippets from the opera nothing exists on tape of him singing that opera. Björling died suddenly of a heart attack in September 1960 and was replaced in the recording by Carlo Bergonzi.

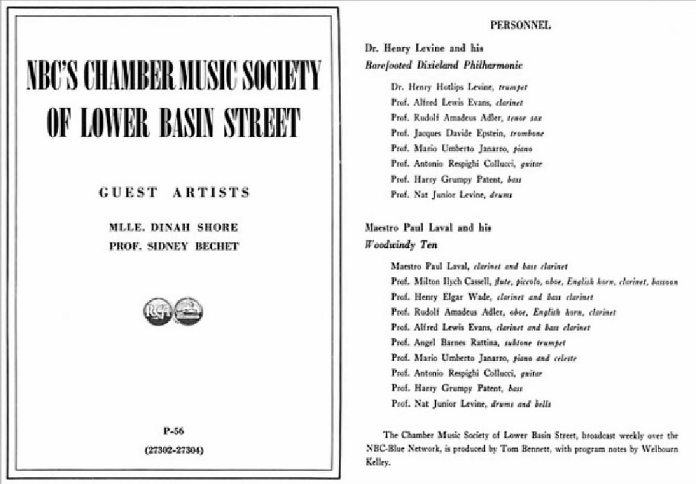

Imagine my surprise, then, to be in a Greenwich Village used-78-record shop in 1968 and seeing an album of records with a cartoon drawing of a guy in a powdered wig playing the trumpet on the front cover. The title of this was The “No Doubt Famous” Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street, and when I bought the records, took them home and played them, I was immediately in thrall of the bizarre, tongue-in-cheek description of the opening selection, the old ODJB standard Satanic Blues:

Imagine my surprise, then, to be in a Greenwich Village used-78-record shop in 1968 and seeing an album of records with a cartoon drawing of a guy in a powdered wig playing the trumpet on the front cover. The title of this was The “No Doubt Famous” Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street, and when I bought the records, took them home and played them, I was immediately in thrall of the bizarre, tongue-in-cheek description of the opening selection, the old ODJB standard Satanic Blues:

The show was a full-blooded parody of the stuffy “music appreciation” shows that presented classical music in a similar vein. It grew out of a quarter-hour series called Bughouse Rhythm and was described by Radio Life as “one of radio’s strangest offspring…a wacky, strictly tongue-in-cheek burlesque of opera and symphony.” Even Milton Cross got in on the act with his opening announcements, describing the musicians on the show as having “consecrated their lives to the preservation of the music of the Three Bs: Barrelhouse, Boogie-Woogie, and the Blues. Present with us on this solemn occasion:

The show was a full-blooded parody of the stuffy “music appreciation” shows that presented classical music in a similar vein. It grew out of a quarter-hour series called Bughouse Rhythm and was described by Radio Life as “one of radio’s strangest offspring…a wacky, strictly tongue-in-cheek burlesque of opera and symphony.” Even Milton Cross got in on the act with his opening announcements, describing the musicians on the show as having “consecrated their lives to the preservation of the music of the Three Bs: Barrelhouse, Boogie-Woogie, and the Blues. Present with us on this solemn occasion:

It happens every year in numerous classical and jazz magazines: the End-of-Year picks for Best In Show. Best Performance by a Chamber Group from a Balkan Country. Best Recording by a Pianist Playing With a Zither. Best Opera Recording (is the award for the opera or the performance? or both?). Best Jazz Performance by a Group Larger Than a Trio Yet Smaller Than a Breadbox. Best Jazz Vocal Recording. Blah, blah, blah. In some publications, each reviewer is asked to whip up a list of recordings they would desperately want if they didn’t already have them or choose which ones from the year they’d take to a desert island.

It happens every year in numerous classical and jazz magazines: the End-of-Year picks for Best In Show. Best Performance by a Chamber Group from a Balkan Country. Best Recording by a Pianist Playing With a Zither. Best Opera Recording (is the award for the opera or the performance? or both?). Best Jazz Performance by a Group Larger Than a Trio Yet Smaller Than a Breadbox. Best Jazz Vocal Recording. Blah, blah, blah. In some publications, each reviewer is asked to whip up a list of recordings they would desperately want if they didn’t already have them or choose which ones from the year they’d take to a desert island.

copyright of ANY published work, whether in print media or recorded media, was 50 years. Period. End of sentence. No caveats, no further restrictions. But then poor little Naxos Records, which had been issuing historical classical recordings under its “Great Recordings of the Century” series for over a decade, started issuing the old mono opera recordings of Maria Callas.

copyright of ANY published work, whether in print media or recorded media, was 50 years. Period. End of sentence. No caveats, no further restrictions. But then poor little Naxos Records, which had been issuing historical classical recordings under its “Great Recordings of the Century” series for over a decade, started issuing the old mono opera recordings of Maria Callas. Somehow or other, EMI was unable to sway British or other European countries into extending the length of copyright time to protect them, but in America they found three willing allies to come to their aid. These were the Walt Disney empire, which suddenly realized that all of those classic songs and animated movies they had made prior to Walt’s death were suddenly about to be pilfered by nefarious people for ill-gotten gain; Sony-RCA, which suddenly noticed that this would affect their stash of Elvis Presley recordings; and Capitol Records, a division of EMI, which also came to realize that the advent of The Beatles 50 years earlier was on the horizon. Thus they managed to get the U.S. Congress—weasels all, and

Somehow or other, EMI was unable to sway British or other European countries into extending the length of copyright time to protect them, but in America they found three willing allies to come to their aid. These were the Walt Disney empire, which suddenly realized that all of those classic songs and animated movies they had made prior to Walt’s death were suddenly about to be pilfered by nefarious people for ill-gotten gain; Sony-RCA, which suddenly noticed that this would affect their stash of Elvis Presley recordings; and Capitol Records, a division of EMI, which also came to realize that the advent of The Beatles 50 years earlier was on the horizon. Thus they managed to get the U.S. Congress—weasels all, and  undoubtedly on the take from one or more of these organizations—to draw up one of the most binding, restrictive and far-reaching laws of all time, to wit, 95 years from the date of publication if copyright was renewed during the 28th year.

undoubtedly on the take from one or more of these organizations—to draw up one of the most binding, restrictive and far-reaching laws of all time, to wit, 95 years from the date of publication if copyright was renewed during the 28th year. In fact, that was the first really restrictive such law on records. The Sound Recording Amendment of 1971 extended federal copyright to recordings fixed on or after February 15, 1972, and declared that recordings fixed before that date would remain subject to state or common law copyright. Subsequent amendments have extended this latter provision until 2067, thus ensuring that some fat corporate pig who hasn’t even been born at this point will be ensured of sloughing off profits from records he doesn’t even yet know exist. Still, even now, all copyrightable works published in the United States before 1923 are in the public domain; works created before 1978 but not published until recently may be protected until 2047.

In fact, that was the first really restrictive such law on records. The Sound Recording Amendment of 1971 extended federal copyright to recordings fixed on or after February 15, 1972, and declared that recordings fixed before that date would remain subject to state or common law copyright. Subsequent amendments have extended this latter provision until 2067, thus ensuring that some fat corporate pig who hasn’t even been born at this point will be ensured of sloughing off profits from records he doesn’t even yet know exist. Still, even now, all copyrightable works published in the United States before 1923 are in the public domain; works created before 1978 but not published until recently may be protected until 2047.