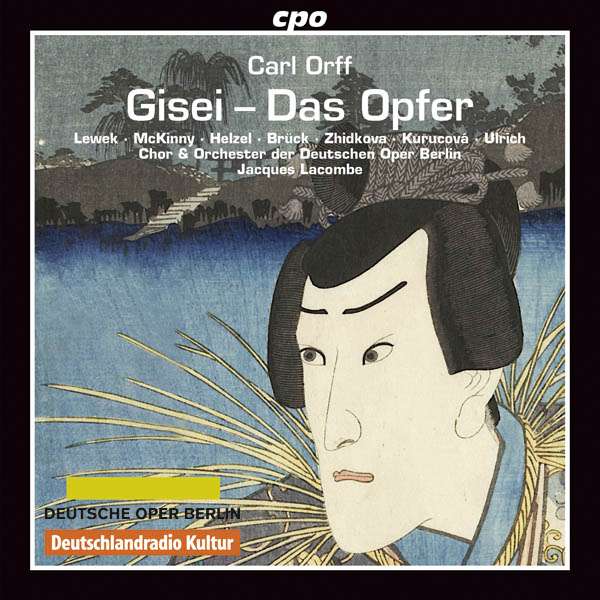

ORFF: Gisei – Das Opfer / Kathryn Lewek, soprano (Kwan Shisai); Ryan McKinny, bass-baritone (Genzo); Ulrike Helzel, mezzo-soprano (Tonami); Markus Brück, baritone (Matsuo); Elena Zhidkova, soprano (Chiyo); Jana Kurucová, mezzo-soprano (Kotara); Burkhard Ulrich, tenor (Gemba); Deutscher Oper Berlin Chorus & Orchestra; Jacques Lacombe, conductor / CPO 777 819-2

And now, as John Cleese so often said, for something completely different. I was curious to hear Gisei – Das Opfer (Gisei – The Sacrifice) because it was a work by Carl Orff I’d never heard or heard of, and except for his dreadful late opera Oedipus der Tyrann I am a big Orff fan; but as it turns out, this sounds absolutely nothing like his later work. This is from the period that Orff declared was dead and forgotten, “inferior” to his music from Carmina Burana on. Except that he was wrong about Gisei. This is a mini-masterpiece.

The music, clearly inspired by Debussy in general and Pelléas et Mélisande in particular, nevertheless has more of a German “sound” and color, particularly in the orchestration which owes a great deal to Wagner’s Parsifal. But then again, Debussy himself owed a great deal to Parsifal, which he heard at the Wagnerian shrine of Bayreuth, so this is to be expected. The point is that this is a very different Carl Orff: there are no repeated melodic fragments or ostinato rhythms here, but a floating melisma of sound, opaque though very creative in carrying the text of the drama—a story based on the Japanese bunraku/kabuki drama Terakoya, which translates as The Temple School. The plot involves the temple schoolteacher Genzo (bass-baritone Ryan McKinny) who instructs peasant boys and his own eight-year-old Kwan Shusai (soprano Kathryn Lewek) in geography. The secret, however, is that Kwan Shusai is not their biological son but but the progeny of the Chancellor of the Right, banished following an intrigue by his opponents in exile. The adherents of the Chancellor, however, have found Kwan, realizing that he is the last hope of the country as the heir of the banished leader. The traitorous samurai Matsuo (baritone Markus Brück), who entrusted Kwan Shusai to Genzo’s care, enters with the tyrant’s men and the Chamberlain Gemba (tenor Burkhard Ulrich), trying to locate and kill Kwan. Desparate to save their country and their ward, Genzo and his wife, Tonami (mezzo Ulrike Helzel), decide to sacrifice a new pupil who looks very much like him and arrived on the same day. Genzo presents the boy’s severed head to Matsuo, who claims to recognize Kwan Shusai…but it turns out that the mystery boy is Matsuo’s own son. He claimed to recognize the head as the son of the Chancellor in order to atone for his disloyalty to his country.

There are several other differences between Gisei and Pelléas. One, of course, is length: Pelléas runs about two and a half hours, Gisei only an hour. Pelléas rises to but one climax, when Golaud kills Pelléas, whereas there are several peaks in Gisei. Yet there is no mistaking the extraordinary quality of the music, particularly for a composer aged only 18 at the time (1913). Have you ever heard so great an opera written by an 18-year-old? I haven’t, either. Not even Mozart was this advanced in his musical thinking—and I am making allowances for the stylistic differences in classical music between 1774 (when Mozart was 18) and 1913. Bright and well-constructed as they are, none of Mozart’s music form age 18 has the depth of expression, the kind of feeling and intensity, of Gisei…certainly not La Finta Giardiniera, the opera he wrote at about the same age. No, this is not a criticism of Mozart, but meant to illustrate just how advanced Orff’s musical thinking was at an extraordinarily early age.

In addition to its high quality in its own right, Gisei – Der Opfer sheds new light on such a later work as Antigonae (1949), one of Orff’s great dramatic masterpieces. It boggles the mind to realize that Orff suppressed Gisei and refused to allow a performance in his lifetime, thus it did not premiere until 2010. I haven’t seen other opera houses rush to put it on, but they should.

As for the performance at hand, it is for the most part of a very high quality, particularly the conducting of Jacques Lacombe who, to my amazement, is the present-day conductor of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra. Why to my amazement? Because I grew up in New Jersey at the time when Henry Lewis, one of the least talented conductors of my experience, was that orchestra’s music director. (At one concert I attended, Lewis absolutely butchered Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra, pushing the orchestra so hard that they produced harsh sounds and one of the violinists snapped his strings. No kidding.) The singing, as is so often the case in modern recordings, is more of a mixed bag. McKinney and Brück both have slow vibratos, which translates into incipient wobbles, though they are not nearly as bad as Falk Struckmann or Kwangchul Youn. Mezzo Helzel is less fluttery and soprano Lewek has an excellent voice. All of them perform their roles with great feeling, which helps in an unfamiliar work like this, and the recorded sound is, thankfully, clear and forward, quite natural without the over-ambient goop that so many record companies pour over their product. This is not likely to become a repertoire piece, more’s the pity, thus I suspect that this may be the only recording we get of it, but it’s certainly fine enough to indicate how talented young Orff really was.

— © 2016 Lynn René Bayley