MR. TRUMPET: THE TRIALS, TRIBULATIONS AND TRIUMPH OF BUNNY BERIGAN / By Michael P. Zirpolo / Scarecrow Press, Studies in Jazz No. 64 ($132 hardback, $49 paperback, available for order HERE)

Michael Zirpolo, the author of this book, was kind enough to send me a copy after reading my appreciation of the Bunny Berigan Orchestra. I had expressed interest because I couldn’t figure out why it took so long for such an obviously talented musical genius to hit the big time and, even more puzzling to me, why he wasted so much of his valuable energy recording a lot of pop music junk in stock arrangements, taking “straight” solos without any jazz content.

Well, I sure found out! But before I get into the details, let me say up front that Zirpolo is not the devil in them, only the messenger, and he did some pretty heavy lifting in preparing this book, particularly in sorting through the voluminous materials on Berigan collected and sorted by one Cedric “Bozy” White over a half-century. This was, as in the case of Phil Evans’ roomful of files on Bix Beiderbecke that had to be sorted out and edited by Richard Sudhalter, a collection of everything plus the kitchen sink, which meant that Zirpolo had to double-check to decide what was correct and what was hearsay or simply unverified. After White’s death, these materials were further edited by Perry Huntoon and Ed Polic in preparation for a Berigan bio-discography, but as of this writing I could not find such a book yet being published. Another source for Zirpolo was Robert Dupuis’ biography, Bunny Berigan—Elusive Legend of Jazz (Louisiana State University Press, 2005). It is to Zirpolo’s great credit that he somehow made a coherent, readable and not too contradictory narrative out of all these materials, some of which conflicted with each other. The book reads well. That’s not the problem. The problem was Bunny.

Let me put it this way: Roland “Bunny” Berigan had one heck of a messy life after he came to New York, a messy marriage, and a VERY messy career. In fact, despite the fact that his professional duties paid him extremely well during the height of the Depression and also made him well known among the musical fraternity prior to 1935, he so overwhelmed himself with a daily grind that often encompassed 12-hour days and played so much pap that he would rather not have done that it was what started him on the path to becoming an alcoholic. He apparently didn’t really start drinking until about 1931, but by the end of 1934 he was, as Zirpolo describes it, a “functioning alcoholic” who once showed up so loaded for one of Benny Goodman’s Let’s Dance radio programs that he fell off the riser for the trumpet section and had to be replaced mid-broadcast.

Moreover, his personal life was also a mess, again mostly of his own making. Wanting to duplicate the happy home life he had enjoyed in Fox Lake, Wisconsin, he married not a level-headed woman who could have provided him a stable home life but a 19-year-old vaudeville dancer whose head was apparently stuffed with sawdust. She saw marriage to the handsome, talented and affluent Berigan as a potential bundle of laughs. She had no housekeeping, budgetary or parenting skills, and by 1934 she simply took to joining Bunny in getting loaded whenever he was home . They were a rollicking, carefree couple who pissed away thousands of dollars that should have been reinvested in Bunny’s career, hiring an agent who could have lined him up more fulfilling and less exhausting work, and put his name before the public in the few really hot bands that existed at the time, primarily the Casa Loma Orchestra. True, like all “dance bands” the Casa Lomans had to play its quotient of sweet tunes along with the hot, but just listen to their arrangements from that period: all of them tasteful and many of them tremendously complex and exciting jazz. By 1933, as Zirpolo points out in this book, the Casa Loma Orchestra had lined up a lucrative radio wire that paid them top dollar during the Depression. Bunny would surely have benefited from this exposure regardless of how many recording dates he shoved into his busy schedule, but instead he made the bad career decision to work for Paul Whiteman, who scarcely used his talents properly, from November 1932 to November 1933.

And believe me, Berigan did a LOT of recording, mostly for the American Record Corporation (ARC), which sold their records inexpensively in department stores, but also for the cheapo “Hit of the Week” and such major labels as Brunswick, Columbia and Victor, the former with his drinking buddies the Dorsey Brothers. This activity included several outstanding sides with the only real white jazz vocal group of the day, The Boswell Sisters, and in fact Berigan gave what I consider to be his first fully mature jazz solo on their February 24, 1932 recording of Everybody Loves My Baby (you can listen to it HERE, Track 25). He first met Tommy Dorsey at Jimmy Plunkett’s speakeasy in 1930, became a good friend, and even after he became the “first call” trumpeter for every musical assignment under the sun, particularly at CBS radio where he practically played from noon to midnight every day, he was the Dorsey Brothers’ favorite trumpeter.

Yet another dumb career decision Berigan made: in 1934 he refused Tommy’s offer to be part of the full-time, road-traveling Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra which, again, played a much higher quotient of jazz than the average pop band. He turned down the chance to become nationally known under a leader who was a genius at promotion in order to record garbage music with Fred Rich, Freddy Martin and others.

Why? Zirpolo explains it, I think, exquisitely well on p. 37:

For the most part, Berigan took these new challenges in stride. His pleasant, easygoing personality allowed him to bend, not break, under the new stresses…But Berigan had insecurities as well. The tenor saxophonist Bud Freeman noted that “Bunny wanted everybody to love him. He was terribly insecure.” When Bunny joined CBS, he did not know if his playing would receive the praise and approval it had always received, and this bothered him.

Substantial self-confidence is not the same as unlimited self-confidence. The great virtuoso bandleaders who eventually came to fame in the swing era, most notably Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, and Artie Shaw, seemed to possess unlimited self-confidence. They each had, in addition, a colossal ego. They pleased and offended people with little regard for what others thought of them. They each withstood the pressures, problems, and successes of simultaneously being a virtuoso instrumentalist and a bandleader, in their own ways, but self-doubt was simply not present in any of their personalities. Bunny Berigan did not have unlimited self-confidence, nor did he have a giant-sized ego. Instead of reaching within himself and tapping some inner reserve of emotional strength when confronted by major challenges, Bunny began to reach for alcohol to soothe his nerves and bolster his self-confidence. At about the time Bunny joined CBS, Plunketts became, increasingly, not just a place to relax after work, but a place to go at all hours to obtain the liquid courage he thought he needed to play well, and get through whatever situation he found himself in.

Sad but true…and for some reason, not even seeing one of his idols, Bix Beiderbecke, passed out in Plunkett’s after a two-hour morning recording session, or worse yet, seeing and hearing him in a completely debilitated state in the spring of 1931 when both men played on the same remote dance band gig, seemed to make any impression.

Compare this to the career trajectory of Berigan’s primary trumpet idol, Louis Armstrong. Louis may have had more of unlimited self-confidence than Bunny, but he was a poor, under-educated black man from New Orleans who, as he often put it, “don’t speak any language but English and that one not too well.” The difference was that he married a woman who was not only a well-trained musician but also a highly intelligent and very well-educated one, Lil Hardin, and Hardin knew how to both manage a home budget and promote her extraordinarily talented husband. It was she who encouraged him to quit King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band near the end of 1924 to join Fletcher Henderson’s pioneer big jazz orchestra in New York, and despite his “hayseed” ways (Louis wore short trousers that exposed his red long underwear, and brought a bucketful of red beans and rice onto the bandstand every night to eat for his supper) he made a deep impression on his more sophisticated bandmates. Then, it was Lil who told him to go back to Chicago where she was able to set him up in some of the best hot jazz orchestras in the city such as Carroll Dickerson’s Savoyagers (which Louis eventually took over), lined up the OKeh recording contract that produced his legendary Hot Five and Hot Seven discs, and thus made him a big name in the “second city.” True, it was Armstrong himself who accepted Joe Glaser’s offer to manage him, and it was Glaser who made him an international star in a very short period of time, but throughout all this period Armstrong never did more than a little social drinking. He was never an alcoholic, kept his eye on the ball, and carved out one of the greatest careers in jazz playing (for the most part) what he liked along the way.

Although Joe Glasers didn’t grow on trees, there were still things Bunny could have done, like seek out Willard Alexander, the most jazz-hip of the big booking agency employees, to help promote his career—and manage his drinking. Yet Bunny continued to make poor career choices in those early years, over and over again. He used to drop in to the Onyx Club, one of the three biggest and most popular jazz clubs in New York (along with the Famous Door and the Hickory House), after hours to jam with the other guys—and not get paid for it. If he had only been able to persuade one of the owners of these establishments to give him his own band, he’d probably have landed a continuous recording contract as Wingy Manone did at the Hickory House, followed in turn by clarinetist Joe Marsala. There were just a lot of options open to him, yet he constantly made the wrong decision, like playing with with Whiteman. That was practically a lost year for Berigan, bringing him nothing but a chance to visit his family back in Fox Lake when the Whiteman band played a week or two in their neck of the woods.

In Berigan’s case, lack of unlimited self-confidence led to his making bad decisions, those bad decisions led to more frustrations, and more frustrations led to his drinking heavier and heavier. By 1935 he had become so unreliable that only those bandleaders who felt that they needed a sparkplug like him in their bands, Goodman and Tommy Dorsey, were willing to take a chance on him, and he didn’t last long in either orchestra despite recording brilliant solos with both that are now considered jazz classics. Most people don’t realize that Bunny’s first Goodman discs, the ones that made his name (King Porter Stomp, Blue Skies, Jingle Bells, Get Rhythm in Your Feet), only had him as a guest in the studio. He wasn’t a regular member of the band until July, when he made the trip out West that culminated in the Palomar Ballroom gig in late August—and instead of staying and reaping the benefits of being with the then-hottest band in the land, he left again to return to the daily grind of CBS radio work, adding to it full-time work at the Famous Door with a small band and what seemed like four times as many studio recordings as in previous years during 1936.

But this time, Bunny almost inadvertently lucked out. CBS radio, wanting to cash in on what they perceived as the “swing craze,” gave him regular broadcasts with his own small group, Bunny Berigan and his Boys and, later in the year, featured him prominently on a show called the Saturday Night Swing Club. And miraculously, it was during this year that Berigan actually went on the wagon for a couple of months. Why? Because he was finally trying to set up his own permanent, full-time orchestra under his own name, and Rockwell-O’Keefe wasn’t interested in booking a bandleader with a reputation for showing up drunk on the job and sometimes playing so sloppily that it damaged his performing ability. While putting together his band, Berigan played for two months as “guest hot soloist” with Tommy Dorsey on broadcasts and recordings, during which time he recorded two masterpieces in one day, Marie and Song of India.

But then, more mess came into Bunny’s life in the form of a torrid love affair with singer Lee Wiley. She wasn’t the marrying kind and Bunny knew it, she was more of a femme fatale (in fact, she had just cut off a long love affair with bandleader Victor Young), but he was still drawn to her like a moth to a flame—and he clearly didn’t need this kind of complication on top of all his other problems.

So then, after all these years of hard work, endless gigs, and tons of recordings, the Bunny Berigan Orchestra was finally formed…and it stunk. Why? Because Bunny, always wanting to please people and be liked, had hired a group of young musicians who were pretty good individually but had absolutely no experience playing in sections. Besides Berigan himself, the only other pro in the orchestra was clarinetist Matty Matlock, an old friend on loan from the Bob Crosby band. At their first recording session, they spent two hours rehearsing a song that turned out to be the wrong song with the same title, so Bunny had to run out ahd buy a stock arrangement of the right song, touch it up and reharse it. At opening night of their two-week stay at the prestigious Meadowbrook, they were so awful that even well-wishers and friends of Bunny’s were embarrassed for him, and them. By the time the engagement ended they had nowhere to go because nobody wanted them. Back to the drawing board! Audition, replace, rehearse! But to his credit, Bunny finally got it right by March—thanks, in part, to the dissolution of Artie Shaw’s first band and a few musicians with Tommy Dorsey who were sick of his tantrums. As confirmed by Berigan’s early band singer Carol McKay,

Bunny was very definite about what he wanted soundwise. He and Joe Lippman worked closely together on most numbers and got along well. Bunny would make quite a few suggestions about how the brass was to be written for.

Here’s an interesting fact: the book spends 150 pages covering Berigan’s entire life and professional history from the time of his birth to February 1937, when Bunny was 28, whereas the rest of the book covering just the last six years of his life runs 347 pages (not counting the Appendices). Of course, Zirpolo does a lot more in those 347 pages than just to cover Berigan’s own playing and personal life. He uses them to discuss the business end of the band business, how the musicians were controlled by their agencies, bookers, sing pluggers and unions in terms of repertoire, particularly in what they were told to record. For someone like Berigan, who just wanted to make music and be loved and leave the business end of it to someone else, this again didn’t work out too well. As I said earlier, he really needed a “personal manager” act as a liaison between the musicians and The Machine for him. He wasn’t the kind of person, as Artie Shaw, Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller were, to check up on things and make sure everything was running smoothly. Benny Goodman had John Hammond running tackle for him, as he later did for a few years for Count Basie, and Duke Ellington ran his own show, but Bunny had the business acumen of a Millennial living at home with his or her parents. He wasn’t a babe in the woods, he was a babe in a vicious jungle, and to some extent it amazed me that all those years of working in studios, for networks, for Whiteman etc. hadn’t taught him a single thing except how much liquor he could sneak onto the bandstand while he was playing a gig.

And yet, somehow, Berigan adapted. I won’t go into all of the details that he ran into while running his band—it’s better for the reader to have some surprises in store—but as a woman I was surprised and delighted to read that Bunny didn’t like the idea of his female band singers sitting on the stage when not singing. He felt that it “cheapened the singer (according to McKay) and took away the element of surprise.” Bunny also personally discouraged audience members talking to the “girl singer” during a gig, “trying to get a dance or a date.” Another mixed blessing was in Berigan landing a recording contract with Victor Records, which he and others considered to be “the Cadillac of record companies.” The problem was that his management, Rockwell-O’Keefe, which had done well by him so far and gave him personal attention, had most of their bands tied up with Decca. Berigan’s band was picked up by MCA, in their own way the “Cadillac” of booking agents, but they gave him far less personal attention, which he needed. But this was not entirely due to the RCA contract; Bunny’s good friend Tommy Dorsey was also with MCA, his recording of Marie/Song of India with Bunny’s solos on it was selling like hotcakes, and TD always had a finger in the pie of every business decision. He probably somehow wangled a cut for himself by getting the “hottest trumpeter in the business” over to MCA.

Del Sharbutt, the announcer for one of Berigan’s radio broadcasts, put it succinctly:

Bunny was a hell of a musician, like a very talented child, but he wasn’t a strong bandleader, not really cut out for it. His drinking was starting to get really bad—not that he was drunk on the job—he just had to have it to function at all. The sign of a true alcoholic I guess.

But when it came to the musical side of the band, Berigan knew what he was doing. He eventually got the kind of well-written, highly-swinging arrangements he wanted as well as the jazz soloists he liked best, including clarinetist Joe Dixon, tenor saxist Georgie Auld and trombonist Sonny Lee. As Lee put it:

The band worked harder than any other band I was with, and Bunny worked harder than any other leader I ever knew, even when he was ill.

Pianist-arranger Joe Lippman also added the following:

Bunny was particular about musical detail like most good musicians…There was an awful lot of pride in those Berigan bands. Like most of the groups of that day, we wanted to be better than anybody.

And Bunny wanted to be loved—not just by his musicians, but by the audiences he played for. He absolutely glowed when they showed him appreciation. Yet he never understood that all of those horrible records his band made of third-rate songs forced on him by the song-pluggers were damaging his reputation. Ah, he’d say with a wave of his hand, we’ll just wow ‘em in person. At least the recording dates are paying us good money, which we need. It never seemed to dawn on him that all of those awful songs were actually damaging his “brand.”

I’m not really trying to make this review sound cynical; after all, I do adore Berigan’s playing and always will; but really, going over his shortcomings wasn’t just frustrating, it was maddening. Put any other name into the above narrative you’d like, let’s say someone who was a good musician but not a genius, and I think you’ll understand how I feel. The fact that all of this happened to a truly GREAT musician whose music still moves people nearly 80 years after his death just makes it doubly frustrating. You either feel like tearing you hair out or reaching back in time and tearing Bunny’s hair out. It’s that weird of a story. He succeeded professionally at what he did, which was to play the trumpet better than any other white musician of his day, but otherwise just kept falling into open manholes that he himself took the covers off of.

Like the Lee Wiley affair, which came back to bite him when his wife Donna—by now also a confirmed alcoholic—found out about it and confronted him. Bunny stupidly told her that he’d take Lee over her. Eventually, Donna began physically abusing his daughters, which was something Bunny could not tolerate; he rushed home to defend them, then had his parents come out from Wisconsin to tend to them because he couldn’t trust his wife. (Band musicians who met her all said, in later years, that even before this she was a terrible mother and housekeeper. She thought life with Bunny was all going to be amusement park rides, circuses, rainbows and Unicorns, and had no idea how to be a wife and mother.)

Berigan’s professional career began a slow but steady descent towards the end of 1938 and into 1939. Part of it was because his reputation as an unreliable alcoholic preceded him everywhere he went, but there were two incidents—one his fault and one the fault of his personal manager at MCA, Arthur Michaud—that did him in. The first was when, coming on stage sloppy drunk, he fell into the orchestra pit and couldn’t get out for several minutes when the band had to play without him. That one was on him; it made the rounds in the press; and it cost him gigs. The second was when MCA booked him into a theater in BRISTOL, Connecticut, but Michaud mistakenly told him it was BRIDGEPORT, Connecticut. Berigan went where he was told to go, actually set up early, but then saw the fairly new Gene Krupa band come in and set up and learned the truth. By the time he and his band made it from Bridgeport to Bristol, the theater had closed for the night and he was sued for breath of contract. Yet although this wasn’t his fault, he compounded the error by just sucking it up instead of hiring a lawyer and suing Michaud and MCA for giving him the wrong information.

As a sequel to this mess, Berigan rightly fired Michaud as his personal manager but wrongly refused to hire a new one. This threw him at the mercy of MCA, which now simply booked him on endless, costly, zig-zagging road tours which made him lose money rather than making it. His band fell apart when Artie Shaw began hiring some of his best sidemen away from him, including star drummer Buddy Rich. Berigan rebuilt his band with mostly unknowns who actually played extremely well, and by the spring of 1939 he had a great band again…but being relegated to the road and having very few radio broadcasts, no one knew about it. Prior to his firing, Michaud had kept promising Bunny that his band was going to be signed to a major radio program, probably Bob Hope’s, or at least featured in a major motion picture, but neither ever happened. Zirpolo places the blame squarely on Michaud for this, but to be honest, Bunny’s reputation as an unreliable boozer probably had a lot to do with his not getting these prize jobs.

So down the rabbit-hole he went, taking great pride in the musical discipline and performances of his band but slowly losing money as if it were seeping down the middle of an hourglass. And yet, his musicians stayed with him and other, more famous musicians continued to admire him, mostly due to his incredible talent but also because he was basically a very lovable person. Bunny smiled, schmoozed and drank himself into debt, all the while still performing at a peak level.

Of course, there were musical reasons why Berigan’s big band never quite hit the heights. As I mentioned in my previous article, Bunny as a rule didn’t like riff tunes; he preferred the older jazz compositions because he liked their form and structure, so his band played a lot of them, but unfortunately for him, riff tunes were where it was at and the old stuff was considered corny by young jitterbuggers. Secondly, at least half of his book seemed to consist of stock arrangements, particularly the pop tunes and ballads, whereas the other half consisted of specialty arrangements by Joe Lippman (and Abe Osser), later Ray Conniff and others, with a wide diversity of orchestral styles and voicings, and this did not help him establish an identifiable band “sound” except for his own trumpet. Artie Shaw very cleverly let Jerry Gray and himself write his band’s book in a consistent style that the public could get used to. And thirdly, although Bunny rightly thought very little of whatever singers were singing the pop stuff, having a revolving door of female singers hurt him in establishing an identity. Goodman was very fortunate in his series of female singers, going from Helen Ward to Martha Tilton, then to Mildred Bailey for a couple of months, then Helen Forrest and eventually Peggy Lee, over a course of six years. Berigan, by contrast, went through female band singers as if they were Kleenex: Carol McKay, Sue Mitchell, Ruth Bradley, Gail Reese (an improvement on the preceding but not great, and all of these just in 1937), Ruth Gaylor, Jayne Dover, and then Kathleen “Kitty” Lane (his best singer, courtesy of Glenn Miller who decided to go with Marion Hutton instead). Musicians didn’t care but, since live performances and broadcasts of even the hottest bands had to include at least four dorky pop tunes per set, the public did. Without a specific “band identity,” Berigan “confused” non-musical listeners too much. Yet he had a very large minority following among those swing fans who understood and appreciated what he could do on the trumpet, and they often followed him from gig to gig or at least came from far and wide when he played a major venue for a week or more, which is what gave him “record attendance” at such venues. Even in the context of the book, Zirpolo states that the Berigan band was marketed by MCA as “The Miracle Man of Swing,” putting the emphasis on him rather than the orchestra.

By 1939, Berigan’s decision to go without a personal manager began to cost him dearly. He was playing more one-nighters than ever, but even when he did have longer and more successful engagements in hotels and theaters, he and his band never seemed to get paid what was due. Bunny finally hired his father, whose only business experience had been selling candy as a traveling salesman and then later operating a small general store, as his personal manager, but the gate receipts kept mysteriously disappearing. To put it bluntly, MCA was playing a sophisticated game of “rolling the drunk,” and doing a good job of it, too. One week, when the band was in Chicago and the musicians hadn’t been paid in a few weeks, Berigan suggested that they go visit the Musicians’ Union President, James C. Petrillo. The error he made was in not also going himself to plead his case. Petrillo got the musicians their current and back pay out of MCA, but somehow felt that Berigan was complicit in this scheme, which he wasn’t…in fact, it was while in Chicago that he first filed for bankruptcy, repeating the action in New York where he was technically a resident. But that didn’t stop Petrillo from fining Berigan $1,000 for bad business practices instead of MCA, who probably told Petrillo that Bunny, and not they, were to blame. And so the merry-go-round went. More messiness in Berigan’s business and personal lives. Bunny’s drinking was by now not only affecting his relationships (he even got into screaming matches with Lee Wiley) and his playing on occasion, it was also affecting his mind, erasing whatever business sense he had learned in his early days.

It was also in 1939 that Berigan finally went to a doctor because he was feeling so awful and learned that he had cirrhosis. A death sentence in those days; the only question was how much longer you could extend your life by giving up the booze. The doctors recommended that as well as stopping playing the trumpet for an indefinite period of time, perhaps six months to a year. Bunny did neither. His compromise was to cut back on his drinking, which is kind of like pouring only a cupful of gasoline on a fire instead of a bucketful. The fire still burns and destroys. With his hands and legs badly swollen, Berigan had to take 18 days off from his band from Christmas Eve 1939 into 1940, during which time others led it (including a few famous guests such as trumpeter Wingy Manone and trombonist Jack Teagarden) and, when he returned, he was still in pain and walking quite unsteadily with a cane. His band musicians were frightened. Could this be the end?

To be fair to Berigan, let us step back and consider the free-boozing jazz scene of the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s, by which point many musicians had switched over from liquor and marijuana to heroin. There were a LOT of alcoholic jazz musicians during that period, both white and black, among them Manone, Teagarden, Eddie Condon, Pee Wee Russell and Wild Bill Davison, the last-named being someone who could have drunk W.C. Fields under a table—and none of them developed cirrhosis at such a young age. Even Duke Ellington could put away the sauce pretty well until he was 41, at which age he just stopped drinking. The famous alcoholic jazz musicians who died before age 40, Bix Beiderbecke, Bubber Miley, Dick McDonough and Fats Waller, did not die of cirrhosis. They died of pneumonia as a secondary condition that their weakened immune systems could not fight off. Thus Bunny had a right to be shocked by the diagnosis…except for one thing. As Zirpolo points out early in the book, his maternal grandfather, who was not a heavy drinker, died of “sclerosis of the liver,” a euphemism in those days for cirrhosis, in 1927 when he was only in his 50s. Thus it was an inherited condition that skipped a generation, and Bunny was the unfortunate child who got it. Even so, he should have done what Ellington did and just stopped drinking, but by this time his system was so used to it that he couldn’t handle simple day-to-day operations without alcohol.

Physically and emotionally unable to continue leading a band, MCA placed Berigan in the ranks of Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra. Dorsey was himself going through a financial crisis, albeit one on a smaller scale than Bunny’s. Audiences had gotten tired of his servings of orchestrated Dixieland mixed with ballads by Jack Leonard and Edythe Wright, so he had to revamp. His first big steps were hiring drummer Buddy Rich when Artie Shaw abandoned his orchestra in November 1939 as well as hiring ace jazz arranger Sy Oliver away from Jimmie Lunceford. He also fired Leonard because he thought Jack was trying to negotiate a better deal with another band; his replacement was “that skinny kid with Harry James,” Frank Sinatra. After letting Wright go, he hired pert, petite Connie Haines, then added a pretty hip vocal quartet, the Pied Pipers, within whose ranks was the superb singer Jo Stafford, who he also used for solos. Axel Stordahl was hired to write the ballad arrangements for Sinatra, some of which included the Pied Pipers. With the emergence of Oliver as his preeminent jazz arranger, it made sense to plug Bunny Berigan into those charts (plus revivals of his 1937 hits, Marie and Song of India).

Berigan was with Dorsey from March 2 through mid-July 1940, at which time he was fired for being a hopeless drunk, yet he continued to come and go until early August. To sum up the Dorsey experience, Bunny was initially thrilled to have someone else calling the shots; Tommy convinced him to cut back or, better yet, completely stop his drinking (for a spell, anyway); and all seemed just rosy at first. But unfortunately, the soft, slow numbers with Sinatra took off like wildfire, as did Sinatra himself, and before long TD was playing three or four ballads in his live shows and broadcasts to every one hot number.

But Berigan wasn’t the only one who was displeased with this turn of events. Rich became so bored playing the ballads that he’d either not play at all, just move his hands over the drums as if he were playing, or drop in some out-of-place bombs and paradiddles just to break the monotony. Finally, Sinatra picked up a pitcher of cold water and ice cubes and threw it at Rich’s head. Buddy ducked and it hit the wall behind him. Not satisfied with that, Sinatra then hired some of his goon friends from Hoboken who beat Rich up. (Sinatra was particularly unpleasant towards Connie Haines, too, calling her a “dumb hick.”)

Bunny took it in stride at first but then started getting bored, and the more bored he got the more he drank. The more he drank, the worse his playing got. The Dorsey band landed a prime summer radio show replacing the Bob Hope Program. At that same time his wife Donna came to visit him; Bunny asked Dorsey’s band manager if he could take her out to dinner and have Tommy pick up the tab. The manager said sure. That evening, when Bunny stood up to take his solo on Marie, he fell off the bandstand as he had done with Benny Goodman in 1934. Tommy asked the band manager to show him Bunny’s dinner tab. He had ordered 12 scotch and sodas and a ham sandwich!

Of course I can’t psychoanalyze Berigan, but my educated guess is that he took the same philosophy that Bobby Darin did when he learned that heart disease ran in his family and that most of the males died young: just keep plugging away, do as much as you can while you’re still alive, and the hell with the consequences. This was, however, a very callous attitude towards his daughters, who he adored and who very much loved him back. For that, I cannot forgive him. And even if he had stopped drinking entirely, his liver was so shot already that he’d probably have only lived an extra five or six years beyond when he did.

Yet Zirpolo provides an important clue to what was really wrong with him. Berigan admitted to some of his Dorsey bandmates that the reason he was such a workaholic was that he felt he needed all that hard work in order to bring his trumpet-playing skills to the high level he had perfected. But the more he worked, the more stressed he got, so he took to drink to relieve the tension; and although he could “play drunk,” there were times when he simply couldn’t produce because he was so loaded, so he practiced more. Which made him more stressed. Which led to his drinking more. It was simply a vicious cycle that he couldn’t break, and to be honest, it’s doubtful that even if AA existed in those years that he could have controlled himself. Those who knew him best all said that they were pretty sure that Bunny never drank for pleasure; even in his worst years, he didn’t like being drunk, he just had to be in order to cope. If he completely stopped drinking he’d also have had to completely stop playing the trumpet at the same time, which his doctors wanted him to do, but what was he supposed to do for a living? He was what he was, an out-of-control workaholic-alcoholic. He knew no other life. Berigan didn’t just need AA, he needed a psychiatrist—and a good one.

The rest of Berigan’s story is, for the most part, just as sad and screwed up as the rest of it. After leaving Dorsey, he started another band of mostly unknowns and young kids which he molded into shape. As usual, they played well but, also as usual, Bunny didn’t keep track of the money and MCA rolled him again—he even skipped out on a hefty hotel bill and ended up in jail. After a brief hiatus he started one more band, his last, again with mostly young players; and by accident, hired as a personal manager—his first in years—he didn’t even know, Don Palmer. Much to Berigan’s surprise, Palmer turned out to be the best personal manager he had, keeping track of the money and not letting MCA roll him. But it was too little too late. After two years without a recording contract, he finally got one for the independent Elite label which turned out about seven sides between late 1941 and early 1942. It was Bunny’s last stand.

On May 31, Berigan began hemorrhaging blood and had to be rushed to the hospital. Unfortunately, he was too far gone and there was nothing the doctors could do. He died at 3:30 a.m. on June 2, 1942. His wife was not by his bedside. The priest and the doctors told her there was nothing she could do so she should go home. Instead of saying No. I’m his wife, I’m staying, she went home and heard about his death at 4 a.m. on the radio. But Tommy Dorsey was by his bedside when he died, and it was TD who either paid for Bunny’s hospital expenses and transportation of his body home to Fox Lake himself or helped raise the money to do so. He also started a trust fund for Donna and the two girls along with Benny Goodman and Fred Waring and, in a final gesture of generosity, put Bunny on his band’s payroll and sent the money every week to his wife and daughters. But this didn’t stop Donna from hating Tommy until the day she died because, having seen and heard what a terrible housewife and mother she was, he called her a whore and a disgrace to Bunny.

* * * * * *

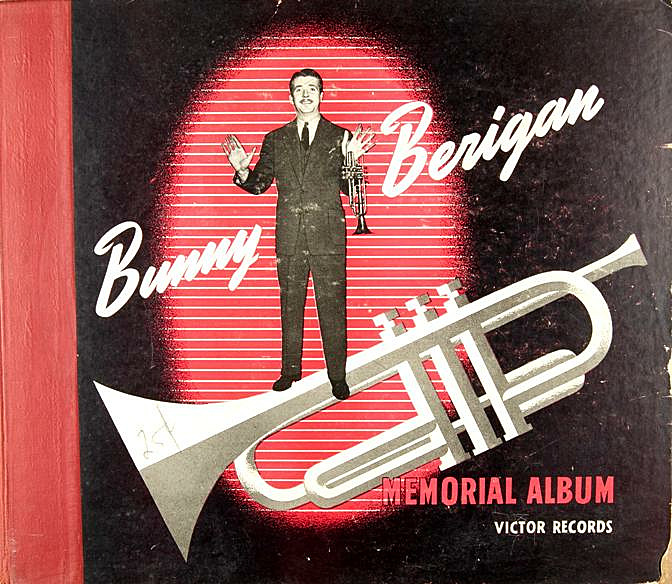

Berigan, like Armstrong, had a tremendous impact on trumpet players of his time, but after World War II a different style of jazz trumpet emerged: the high, blistering-fast bebop style of Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro (who combined the rich tone of Armstrong and Berigan with the speed and dexterity of Gillespie), Red Rodney and young Miles Davis. Bix Beiderbecke had influenced Red Nichols, Jimmy McPartland, Rex Stewart and Bobby Hackett who played in the ‘30s, but his biggest influence was post-bop in the playing of Chet Baker and the new, “cool school” Miles Davis. Yet everyone who came in contact with Berigan on records was impressed because he could actually do more with his instrument than almost anyone else in his time. In 1944 RCA Victor, who hadn’t bothered to record Berigan’s great 1939 band at its peak in May and June of that year and refused to offer him a new contract after his last records for them in September, saw a chance to make a buck on him and so issued the Bunny Berigan Memorial Album (Victor P-134), four 10-inch 78s that included an abridged version of his recording of “I Can’t Get Started” along with “Frankie and Johnny,” “Trees,” “Russian Lullaby,” “Jelly-Roll Blues,” “Black Bottom,” “’Deed I Do” and “High Society.” In 1959 they finally issued an LP of Bunny’s band which included five of these same eight performances (real imaginative, guys!) except that now they used the full version of “Started.”

The book is exceptionally well detailed, in fact a bit too much. Several pages’ worth of the latter part of the book consist of precisely detailed info on dates, locations, times, additional performers and radio hookups of the Berigan band’s itinerary, along with listings of which musicians played on what dates—valuable to the researcher, I’m sure, but as a reader I wished this info had been put in an appendix at the back of the book. Perhaps to save time, and because it has been published elsewhere, a detailed discography is not included, but Zirpolo does list the songs played in both Berigan’s broadcasts and on the Thesaurus transcription discs. There are several typos here and there, most not very damaging except for the misspellings of Paul Whiteman reedman Charles Strickfadden’s last name is misspelled Strickfadded. Otherwise, very neatly done. Zirpolo also omits detailed descriptions of most of Bunny’s solos except for a few occasions when he quotes the late Richard M. Sudhalter. In a way, I understand this; unlike a lot of jazz musicians, Berigan’s solos were full of added and subtracted vibrato, lip slurs, growls and other jazz devices which are difficult to notate, but at least three or four of his best solos of the period (I would say Jelly Roll Blues, ‘Tain’t So Honey ‘Tain’t So, Devil’s Holiday and Tuxedo Junction, his I Can’t Get Started coda having already been transcribed by Gunther Schuller in his book The Swing Era) might have given a visual illustration of the man’s brilliance as an improviser.

Still, this is an excellent bio which dispels many rumors about Bunny Berigan, and is highly recommended to those who love his playing.

—© 2020 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter (@artmusiclounge) or Facebook (as Monique Musique)

Read my book, From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed guide to the intersection of classical music and jazz

Nice article and very well written. Its true Bunny made wrong choices about everything. He should have been the most famous and loved trumpet player and band leader. I think he could have had a band like Count Basie’s. But maybe the way he was brought up had a bit to do with it. If he married someone who was behind him it would have helped. No one can take away his talent and his gift of music. Still one of the greats. I am one of his grandsons. I meant Donna a couple of times. She came to live with my Mom Patrica. My Mom still had things against her. And did not treat her well i thought. It was sad i wish i could have helped Donna. Donna was bedridden. My Mom could not tend to her needs. Donna would have been better to have stayed in Texas. She really loved Bunny. Talked about him so highly. Said no other trumpet player sounded as great as Bunny. Including Louis Armstrong. She said it was MCA that messed up Bunny’s band. He paid them and the manager of his band to do the things it needed and they failed. He listened to the wrong people. Also he drank to play better. But he was wrong in feeling that way. He played better without it. But did not feel relaxed. He mistook that for holding his music back. Like he could let loose with ideas. But he was wrong. Thanks for such a good article.

LikeLike

Have just been listening to your grandfather’s “I Can’t Get Started”. Very enjoyable! I’m wondering whether Bunny’s daughters or grandchildren were/are musicians? That would be a great legacy.

LikeLike