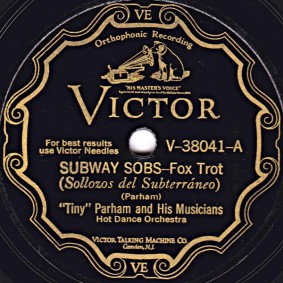

It was in 1988 that the British label Nimbus issued the album Hot Jazz 1928-1930: Original Jazz Performances Remastered, and on it were five tracks by a band I’d never heard of before, Tiny Parham and his Musicians. I was completely flabbergasted, for here were interesting, exotic, and well-conceived compositions combining Sephardic music with ragtime and jazz licks. Why had I never heard of him before? It turned out that Parham, who was Canadian, moved to Chicago in the mid-1920s, became well known as a quick reader and fluent pianist, and by 1928 was leading a 12-piece band simply called His Musicians. Apparently, when Jelly Roll Morton left Chicago for New York at the end of 1927, Victor Records went looking for a local Chicago African-American band that would sell to that demographic, and chose Parham as his successor.

It took me almost a decade to find all of the Parham band’s Victor recordings—to the best of my knowledge, RCA itself never reissued them on either LP or CD—and when I had heard them all my admiration doubled. Desite the fact that his orchestra was trimmed back to seven or eight pieces for recording purposes, which particularly hurt the string section (reduced to one violinist who used a heavy, throbbing vibrato to compensate for the lack of support), and occasional fumbles by the trumpet or trombone soloists, this was clearly a band that played intricate, interesting music that went beyond the parameters of Chicago jazz. Such titles as Black Cat Moan, Cathedral Blues, The Head Hunter’s Dream and Jogo Rhythm not only suggest the qualities of exoticism I heard in his records but deliver this in the form of sliding chromatic passages, downward-moving chromatic bass lines in a minor key, and an extremely clever juxtaposition of themes in such a way that the composition not only builds but continually morphs into different forms and styles. After having heard Parham’s full output (on the European “Classics” label), I made the comment to a friend that it was like opening a Chinese box or one of those Russian Easter eggs that had smaller boxes (or eggs) inside, and smaller ones inside those.

So who was this brilliant man, and why didn’t he build on his success? The answers to the first question were easier to discover than the latter. Hartzell Strathdene Parham was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada on February 25, 1900 but grew up in Kansas City. He worked as a pianist as the Eblon Theatre, where he was praised by ragtime composer James Scott, before touring with territory bands throughout the Midwest and landing in Chicago in 1926. A few records by “Tiny Parham and his ‘Forty’ Four” led to his accompanying clarinetist Johnny Dodds on a few records, following which he formed His Musicians as a full-time performing band.

So who was this brilliant man, and why didn’t he build on his success? The answers to the first question were easier to discover than the latter. Hartzell Strathdene Parham was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada on February 25, 1900 but grew up in Kansas City. He worked as a pianist as the Eblon Theatre, where he was praised by ragtime composer James Scott, before touring with territory bands throughout the Midwest and landing in Chicago in 1926. A few records by “Tiny Parham and his ‘Forty’ Four” led to his accompanying clarinetist Johnny Dodds on a few records, following which he formed His Musicians as a full-time performing band.

Several sources, including Wikipedia, credit Parham with playing music in the Morton style, but this is only true insofar as he favored a two-beat sound rather than the four-four that dominated the scene in New York. The resemblance of Parham’s band to those of Morton is superficial at best; no one would really confuse the two even in a blindfold test. Moreover, though he used Ernest “Punch” Miller as cornetist on several sides, Parham’s soloists are adequate at best, certainly not up to the majority of brass and reed soloists on most of Morton’s recordings. The primary attraction of the Parham recordings are the compositions, and that in itself is astonishing when one considers the state of 1920s jazz.

What I find ironic is that very few scribes have noted the strong resemblance—in form if not exactly in style—to Duke Ellington during his “jungle band” period at the Cotton Club. One can hear the influence of Ellington’s East St. Louis Toodle-O or The Mooche, both of which were signature tunes of his (the former, in fact, being his theme song for nearly a decade) to Parham’s more exotic pieces like Jungle Crawl, The Head Hunter’s Dream or Voodoo. The difference was that, thanks to manager Irving Mills, Ellington was able to record with his full orchestra whereas Parham was not.

The Parham band finally hit the wall in 1930 when Victor pulled the plug on recording him—as they did with nearly every jazz band except Ellington’s. It seems unclear, however, why the Musicians disbanded. Could the termination of his Victor contract have impacted his finances negatively? Quite possibly. In any event, Parham struggled from that point on, eventually finding jobs playing the organ in movie theaters and skating rinks. Near the end of his life he made some recordings on a portable electric organ—lively playing, but not nearly as interesting as his Victor output. Parham, whose nickname of “Tiny” was given him for the exact opposite reason—he weighed more than 300 pounds—died of a heart attack on April 4, 1943 while playing a theater gig in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

With the limited information we have, it’s difficult to say why Parham was either unable or unwilling to write similar pieces for other jazz orchestras during the 1930s. Indeed, in his later recordings he sometimes recorded earlier works at a different tempo with different titles. Perhaps his inspirational well ran dry? We’ll never know for sure, but listening to Parham is a fascinating and joyful experience well worth investigating.

— © 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Listen to Tiny Parham and his Musicians:

Jungle Crawl

Jogo Rhythm

The Head Hunter’s Dream

Black Cat Moan

Stuttering Blues

Voodoo

Tiny’s Stomp (Oriental Blues)

The photo at the top is not Tiny Parham’s Orchestra. It’s Chick Webb’s Orchestra.

LikeLike

By golly, I think you’re right – the photo was misidentified! I have replaced it.

LikeLike

Very interesting article. I have become a fan of him through the “chronogical” series of the french Classic Label. One thing that may be of interest (or a curious thing, at least) is that an argentinean jazz band has dedicated an entire album with his compositions: http://caobajazzband.blogspot.com/2012/04/

LikeLike

So did Pam Pameijer’s New Jazz Wizards back in the early 1990s. I have that album as well.

LikeLike