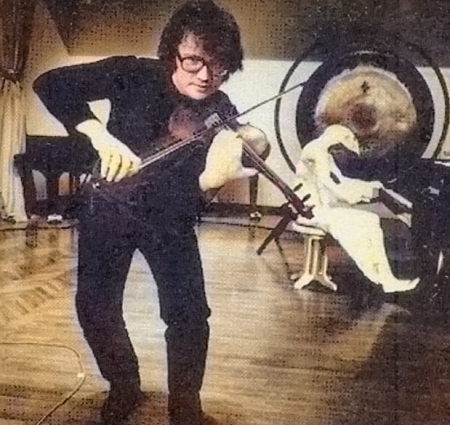

Long before conductor-composer Leif Segerstam looked like this:

He looked like this:

and I know, because I saw him twice in the 1970s and can attest to that.

He was also, even then—perhaps more so, then—looked upon as a radical and, for some critics and listeners, an impossible-to-understand composer. His music seemed to be all over the place, particularly in its rhythm, which was so fluid that even the composer himself referred to it as his “free pulsative” style, but it was the lack of focus (or so it seemed to inattentive listeners) in its structure and development that turned many people off. I, on the other hand, loved it, particularly the chamber music which was what was first imported to New York record stores in the early ‘70s. My particular favorites were A Nnnnooooowww for Woodwind Quintet (1973) and the incredibly freaky String Quartet No. 6 (1974), with its final movement played “in the spirit of Gustav Mahler,” and not just symbolically: performances of this work (especially on the Bis recording) always featured a ghostly figure made of chicken wire and paper-maché who sat at a piano , silently, until near the end of the last movement when the first violinist is requested to back up on the stage and “help” the ghost of Mahler play a contrabass low A on the piano.

Oh, you don’t believe me? Here’s a photo of violinist Segerstam doing just that:

This, then, was a musician who operated outside the mainstream. Just how far outside I didn’t realize at the time since, as I mentioned, his recordings were hard to find even at Joseph Patelson’s Music House just down the street from Carnegie Hall, which also sold some of his scores. And what scores they were! Here’s a page from that same string quartet:

What attracted me to the music of Segerstam, and still does today, is the remarkable feeling and passion in his work. Say what you want of his music, it is not cold and indifferent as in the case of most modern works. Take A Nnnnooooowww, for instance. I think it’s rather hard to find nowadays, although Presto Classical seems to be offering the album (titled Finnish Wind Music and including works by other composers) for download. The wind instruments in this strange work cry and whimper like some wounded alien birds from Alpha Centauri. Definitely not your father’s classical wind music! And that last movement of the String Quartet No. 6 is best listened to in the dark, with the lights out, letting the slow yet weirdly glowing music to wash over you. By the time the last notes die away, you will discover that it is an experience you will never forget.

The Segerstam Quartet circa 1973, Hannele Segerstam on the left.

Indeed, though he has continued to record his own works, the Segerstam of the modern era is known much more as a conductor of others’ music, and to me this is a shame. Of course, much of this is due to the difficulty of his music: atonal yet charged with emotion, and in many cases Segerstam not only encourages but demands spontaneous choices of his musicians. When I was younger, I thought this entailed improvisation, particularly since he played his Rituals in La with Lasse Werner who was a jazz pianist, but in most cases this involves “choosing” different development sections and/or mixing and matching his separate themes in different ways. Thus, for instance, in his String Quartet No. 7, the players are asked to choose the themes of the last movement in a different order each time they perform it. Things like this have driven both performers and critics crazy trying to make sense of his fluid, fluctuating, “free-pulsative” scores.

But who exactly is this man, other than the Brahms-like figure with the white beard who now waves his arms at orchestras like an inspired madman? Born in 1944, he studied violin, piano, composition and conducting at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki. receiving his diploma in violin and conducting. In 1962 he won the Maj Lind piano competition and made his debut as a violinist that same year, continuing his studies at Juilliard in 1963, where he studied conducting with Jean Paul Morel and violin with Louis Persinger—yes, the same Louis Persinger who had taught Yehudi Menuhin! After earning his conducting diploma in 1964 and his post-graduate diploma in 1965, Segerstam returned to Finland where he led the Finnish National Opera for three years. During this time he was also a guest conductor with numerous Finnish orchestras as well as touring with the Finnish Ballet. He became a conductor at the Stockholm Royal Opera in 1968, where he was appointed principal conductor in 1970 and Music Director in 1971. He also conducted opera in Berlin and, in 1973-74, was general manager of the Finnish National Opera.

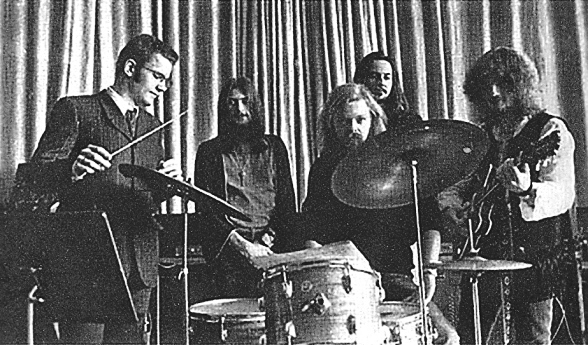

Oh, yes…in 1969 he also conducted a performance (I know not of what) with the Swedish rock band, the Mecki Mark Men. Here’s the picture to prove it:

So Segerstam was pretty strange even early on, but it wasn’t until I read some of his comments—about his own music and comments to orchestras in rehearsal—that I realized just how strange. I guess the bottom line is that he was just as odd as his music. Here, for instance, are his comments on A Nnnnooooowww:

This music of mine speaks for itself and it speaks out of its performers, in their chain of motivations for their utterances in sound of their music-making—NNNNOOOOOWWWs when the music actually iiiiiiiiiiis. How was it, and what was it, now,? This time ? Please reset yourself to positive zero before you listen to my piece!

Or these notes to his String Quartet No. 7:

I felt it was an espressivo-music, mostly even semprei espressivo possible…! the roots are in the expressionism of my previous quartets (Nos. 4, 5 & 6) and later chamber music…Because of the Free-pulsativity this work always makes its own new form so it was worth to be pushed through so demandingly as the music-making felt to have to been done this time: The struggle towards the crashes after the almost “Beethovenia!” trials to find an outlet and ending of the first movement…PLEASE SHARE SOME OF THE STRAIN IN DECIDING ABOUT ENDINGS BY DECIDING YOURSELF YOUR OWN END-VERSION. Our end-version was ABBABAAB!

This isn’t exactly Igor Stravinsky, talking calmly and rationally about his scores. This is a guy who gets REALLY wrapped up in his music, and to a certain extent in others’ music. Here are some of his comments made to orchestras in rehearsals:

Could we have a relatively normal beginning?

Like an old-time Western locomotive, we can get the organity of the puffing…

The string section without the basses is a plasmatic living cluster.

A sort of indignated way of playing before the “la minore” explosion.

Was this a conspiration to read my beat?

Just play in your box until you come to the climax…so that we can hear the clappering.

The quintuplet should be freshly and rudely the same as the triplet.

Something is satelliting out of the control of the beated music.

I have words for everything that can be expressed: Coincidentimently, Emryomalic, Electrifically, Fiveishness, Flimmer, Inexclickable, Fengurish five things, I am fluxating in 8.

Please don’t play sloppy dactyls that they don’t know what it is.

You haven’t experienced it because nobody is doing it.

You don’t need to count here. You won’t get lost because at the end I will turn and look at you stoppingly!

Keep the fermata of the rest interesting.

Wait for the Puccini bit in four and make like the diva.

We will enter in the right times, so the shortening is to the left.

Native folkloric haemiolas that you should have in your Mahler blood.

There are people swallowing time.

Watch it! My left hand is looking at you!

I saw Segerstam conduct in person twice. The first was a performance of La Bohème at the Metropolitan Opera on March 9, 1974, a cast which included Teresa Zylis-Gara as Mimi, Edda Moser as Musetta, Luciano Pavarotti as Rodolfo and Mario Sereni as Marcello. His tempos were on the slow side (as they still are, in others’ music, today) but his musical line achingly beautiful, with an almost unbelievable transparency of texture and a way of making the music “float.”

It was the most heartfelt, most beautiful Bohème I had ever heard in my life, and I’d heard many of them. I used my opera glasses to see what the conductor looked like, so when the performance was over I could recognize him, seek him out and compliment him. I waited patiently; Pavarotti came out, I got his autograph, and then others began mobbing him; he was friendly and cheerful. The out came Segerstam; he was watching everyone gathering around Pavarotti. No one noticed him or knew who he was, but I did. I approached him—he looked rather surprised—and I said to him, “I want you to know that that was one of the most beautiful Bohèmes I’ve ever experienced in my life, Can I please have your autograph?” He gave me a quizzical look and said, “I was the conductor.” I have him a very big smile and said, “I know. Thank you so very much!’ His eyes were bright and smiling, and he signed by program. (After I got his autograph, the Pavarotti bunch noticed him and came over, too, even though some of them still probably didn’t know who he was.) That is the most prized autograph I have.

The second time was after I had moved out to Ohio, a performance with the Cincinnati Symphony on November 10, 1978. One of the pieces on the program was his own wonderful Sketches From “Pandora,” a performance so good that it easily surpassed his studio recording of the same work. Afterwards I talked to some of the orchestra musicians, who told me that they enjoyed working with him because he knew his music but found him “a little weird.” After having learned of the strange things he says in rehearsals, I now know why.

The reader should not come to the conclusion that I am poking fun at Segerstam. On the contrary, I have the highest respect for him, and still manage to occasionally follow his career through recordings. Among my favorites are his set of the Sibelius Symphonies and Berg’s Wozzeck. As of this writing, he is scheduled to release a set of recordings juxtaposing his own symphonies (some of them, anyway…he’s written over 300!) with the four symphonies of Brahms. He remains a fine musician, no question about it, but for me, personally, there was something exciting about discovering him for the first time and being part of a “secret clubhouse,” one of a select few people who “got” Leif Segerstam. He remains one of the great musical experiences of my life.

— © 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Read my book: From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed history of the intersection of classical music and jazz