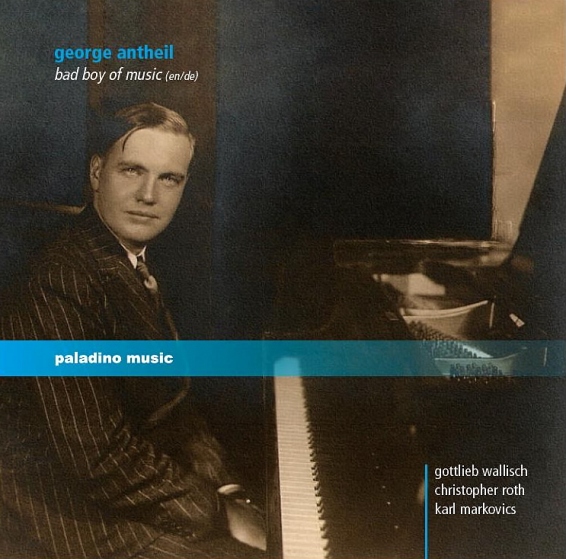

GEORGE ANTHEIL: BAD BOY OF MUSIC / ANTHEIL: Fireworks and the Profane Waltzes. Jazz Sonata. Sonatina, “Death of the Machines.” Second Sonata, “The Airplane.” Sonatina for Radio. Little Shimmy “Für mein nur einziger Böski.” The Golden Bird, after Brancusi. Piano Sonata No. 4: III. Finale: Presto / Gottlieb Wallisch, pianist; Christopher Roth, English narrator; Karl Markovics, German narrator / Paladino Music 0075

This is one of the very few recitals devoted entirely to the music of the American “bad boy of music,” George Antheil, and according to Arkivmusic the only recordings of Fireworks and the Profane Waltzes, only the second recording of The Golden Bird and only the third of the Sonatina for Radio. Since there are spoken narrations from the writing of Anthiel between each number, there are two CDs, one with narration in English and the second with narration in German but with the same music programmed in the exact same order.

But this scarcely tells the whole story. Those unfamiliar with Antheil, or those who only know him from his most famous composition, the Ballet Mécanique, will have no idea what they are listening to. Antheil, who studied piano with a pupil of Franz Liszt (Constantin von Sternberg), was so obsessed with music that he played it “16 hours a day” according to his friend Ben Hecht, “until he had to cure his swollen fingers in an ice bucket.” He apparently hammered the keyboard as if his hands were sledge hammers; thus one would think that the best possible pianist for his music would be a super-virtuoso like Marc-André Hamelin, who has indeed recorded his Jazz Sonata.

Gottlieb Wallisch is far from being that kind of pianist. Despite having a wonderful technique, he employs some rubato and plays more sensitively than Antheil apparently did. But before you write him off as inappropriate for this music, hold your horses and look at some of the titles: many of these pieces, in fact most of them, were influenced by the music of The Jazz Age. Antheil, although an American, received most of his “jazz” influence secondhand because he spent most of his career in France and Germany. As I explained in my book, From Baroque to Bop and Beyond, most Europeans—and Americans living in Europe—had no clue what real jazz was. To them, it was just loud, syncopated dance music, much closer related to a sort of noisy ragtime than anything that Bix Beiderbecke, Earl Hines, Louis Armstrong or Jelly Roll Morton were playing. Indeed, I seriously doubt that Antheil ever heard any of these musicians until the 1930s when their names became better known.

But the jazz element, though crude and basic, was still there in between the notes on the printed page, and if a sensitive pianist with an ear for jazz comes to these works, he or she can bring them out, just as one could do for the jazz-influenced music of Erwin Schulhoff or Maurice Ravel. And this is exactly what Wallisch does. He has the kind of technique I describe as “sparkling”: the music literally ripples out from under his fingers, at full volume similarly to the way Hamelin plays, as is evident in the opening work. “Fireworks,” indeed! The Profane Waltzes that follow have all the sparkle one could possibly want, but note how Wallisch can bring the music down to a whisper and stretch out the tempo ever so slightly to provide a few moments of “breathing room” in the music. The effect is almost uncanny, taking these scores out of the realm of dated novelties and making them living, breathing music.

It is evident that Antheil was influenced harmonically by Scriabin and rhythmically by both “hot jazz” and Stravinsky. As the liner notes confirm, “Antheil’s compositions are…more like collages, with intentional inconsistencies, gaps and fades. They question categories like ‘form and ‘taste’ in a way that seem oddly modern.” I happen to have Hamelin’s recording of the Jazz Sonata, and although it is powerful it doesn’t swing. Wallisch makes it swing. Right or wrong? If you compare it to such ragtime novelties of the time as Zez Confrey’s famous Kitten on the Keys, it’s wrong, but if you compare it to Jelly Roll Morton’s Shreveport Stomp, contemporary with Confrey, it’s right.

Since I don’t speak German, I skipped the German-language disc entirely, but I can tell you that English narrator Christopher Roth sounds far too polished, polite and professional to even come close to capturing the nervous energy that was Antheil, so you have to stretch your imagination and listen to the words rather than the delivery. It’s wonderfully colorful and even a bit surreal at times, as when Antheil describes living across from the Trenton State Prison listening to inmates digging tunnels under the ground at night! The narration also fills in a lot of info on the progress of Antheil’s career, how he managed to find a good agent, how he assembled his programs (combining Chopin with Schoenberg) to the confounding of old ladies with ear trumpets. He described his manager as looking like Sydney Greenstreet and himself as looking like Peter Lorre. Obviously, Antheil was as colorful in his language as he was in his music. I mean, what other pianist do you know who concealed a .38 automatic under his dress jacket every time he played a concert?

Despite his greater affinity for jazz swing, Wallisch also gets the more mechanical rhythms of Antheil right when they are called for, as in the “Death of the Machines” sonatina which sounds for all the world like a piece from Ballet Mécanique, or the “Airplane” Sonata. Antheil always ended his recitals with “ultra-modern works,” Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Auric, Milhaud, Ornstein or one of his own pieces, particularly Fireworks and the Profane Waltzes or the Jazz Sonata. This flavor is fully captured in the performances on this disc, moments of sensitivity or not. Audience unease and even occasional riots greeted these pieces when Antheil played them, according to the narration, so if you feel a bit uneasy listening to Antheil, that was his purpose! Erik Satie was a huge fan, and when present would applaud wildly at these cacophonous musical outbursts, shouting, “What precision! What precision!” You get the same feeling listening to this disc. Listen, for instance, to the “Airplane” Sonata, where Wallisch stomps like mad through the first movement, but then pulls back on the gas and provides some surprisingly tender moments at the beginning of the second.

Sometimes I felt that the narration, though colorful and informative (in Paris of the 1920s, “pay-to-play” music critics were just as ubiquitous and corrupt as they are now), went on a bit too long. It’s the sort of thing that is intriguing and informative on first listening, but I can see where it might wear thin by the third or fifth. One for-instance is his long narration on the Ballet Mécanique; an interesting story, and colorful as usual, but so what? The music itself isn’t even on this CD. It’s the kind of story that could have been put in the liner notes while an extra piano piece was included on the disc. Of course, this is just my own feeling; it may not be yours.

Still, as your ears wander through this recording, you can’t help but be so totally immersed in Antheil’s world—the world of his music and the world of his colorful anecdotes—that you come out the other end with, at the very least, an appreciation for what he was trying to do, even if what you hear isn’t entirely to your taste. As in the case of Schulhoff’s jazz-influenced piano works, Antheil’s music can be heard as a precursor of more modern jazz piano works, whether or not those future jazz composers actually heard Antheil and Schulhoff or not. The point is that the music that influenced them, Stravinsky, Milhaud and Schoenberg, also came to influence Thelonious Monk, Dave Brubeck and others. The stream of musical influence is, and has never been, a straight line; it swirls and eddies around the rocks and broken branches that are in the river. And sooner or later, some jazz pianists must have run across Antheil; up until his untimely death in 1959, you could hardly have ignored him.

This, then, is a very fine album, a bit pricey considering that you’re only buying the second CD to get the same music with German narration, yet valuable nonetheless.

—© 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Read my book: From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed guide to the intersection of classical music and jazz