Nowadays, when it seems that countertenors grow on trees and are picked annually by the bushel, we take their hooty, hollow falsetto voices for granted as “authentic” in early music. Yet only a few of them, such as Philippe Jaroussky, Robin Blaze and Andreas Scholl, actually make a sound that is pleasing to the ear and fit into the music well because of their superior musicianship and interpretations, and of course no opera company in the 18th century ever used a countertenor. They used castrato sopranos and altos, and in fact the composers of those operas often stipulated that when a castrato could not be obtained a female soprano or mezzo was to be used.

But there was a time, in the 1950s and very early ‘60s, when one countertenor emerged who could not only sing this repertoire—and earlier repertoire as well—but do so with a natural, beautiful high voice that did not grate the ear. On the contrary, it floated in the stratosphere with an ingratiating loveliness wedded to perfect diction and astounding musicality and breath control, and because the voice was natural and not falsetto he could project it into theaters like Covent Garden in London. He was the toast of New York and, on records, generally hailed by critics as the most wondrous and phenomenal voice of his time.

His name was Russell Oberlin.

How can one describe one’s first exposure to this voice? James Goodfriend, the editor of Stereo Review magazine, tried to do so in a column he wrote in the early 1970s (Hidden Treasures), a decade after Oberlin’s voice went and he had to stop singing. I’ve tried several times myself. But I don’t think any of us could really describe what we heard, because it was so phenomenal and so beautiful as to be almost supernormal. Although it was a voice that could carry, it was not powerful, and the reason it was not powerful is that it was almost exclusively placed in head tone. When I played a cassette tape of his Handel aria album (now issued on Deutsche Grammophon 28947765417) for a colleague in Aspen, Colorado in 1979, he was absolutely flabbergasted by the beauty of the voice and the sheer elegance of the singing. And bear in mind that he came up at the time when the most famous countertenor in the world was the first falsettist to sing in this manner, Alfred Deller.

I contacted Oberlin once, in the late 1970s, by mail to ask a few questions about his voice production. He wrote back that he was busy at the moment (he was in London) but would answer my “countertenor questions” in the future. He never wrote again. Happily, he has since opened up to others and some of the interview videos are posted on YouTube. Born in Akron, Ohio in 1928, Oberlin studied at Juilliard from 1948 to 1951 with Evan Evans, a voice teacher whose pedigree went back to Manuel Garcia, Jr. As Oberlin put it in a 2010 interview, one of the things that was heavily stressed was diction. The old singing teachers used to put it this way: “Put the words in the voice, not the voice in the words.” But of course Oberlin did not set out to be a countertenor; he was a high tenor, and in fact during his student years he made his recording debut as a member of the then-new Robert Shaw Chorale. His breakthrough came shortly after graduation, when he auditioned for Noah Greenberg whose vocal group, the New York Pro Musica Antiqua, specialized in Renaissance and early Baroque music. Greenberg wanted a male voice to sing high parts to balance out some of the shrill sopranos he had, and Oberlin obliged. He has since explained that for him the transition wasn’t terribly difficult because he was a high, almost Irish tenor in the tradition of John McCormack and Dennis Day. As it turned out, however, keeping his voice placed so high on a consistent, daily basis would eventually lead to a vocal collapse by the time he was in his mid-to-late thirties.

Nonetheless, the voice as one hears it on recordings made up through 1962 is not only extraordinary but, I daresay, unique. Just imagine being able to hear a voice that is male in basic timbre but not in quality, a voice that in its lower range retains the beauty of the upper, and whose upper range can occasionally sing loudly but never forcefully. Indeed, I would say that it is the lack of forcing, allied with nearly perfect diction, that makes Oberlin unique and remains unique decades after he retired to teach at Hunter College. The only negative one can attribute to the recordings is in the orchestral accompaniments to his Bach, Handel and Buxtehude recordings. The style is just a bit too lush and romantic in style, despite the fact that the orchestras are generally of reduced forces. This is particularly true in Leonard Bernstein’s recording of Messiah in which Oberlin sings the alto part. On the other hand, Bernstein’s 1959 recording of Bach’s Magnificat with Oberlin uses the proper sized orchestra—though, again, with a more legato style than we now consider appropriate.

Ironically, the man who made Oberlin a star became jealous when the countertenor started branching out on his own to make records. Greenberg was at first supportive of Oberlin in his solo career, but as he began making many more LPs under his own name than with the group, the Pro Musica’s director was jealous that one solo singer was overshadowing the group and tried to curtail his activities. Eventually this led to a rift and Oberlin left the Pro Musica by the end of the 1950s…but not before they had performed and recorded the medieval Play of Daniel together. This was a very creative and imaginative arrangement by Greenberg himself, utilizing musical sounds and techniques he mad picked up from contemporary popular music (including drums, which were never used in music from that era). Premiered at The Cloisters, the beautiful Medieval and Renaissance art museum outside of New York City, it was an instant hit, much to everyone’s surprise. It was even performed on television and the Decca LP of the production was probably the best-selling early music record before the 1970s.

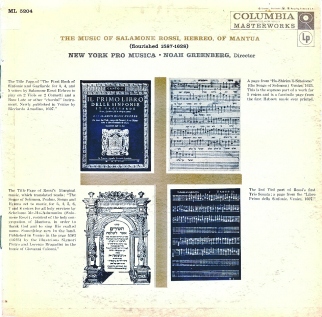

Possibly because the New York Pro Musica performances used what we now consider corrupted sources and editions (not always, but much of the time), nearly all of them are unavailable on CD: the Anthology of Early Music (by “The Primavera Singers of the New York Pro Musica”), Banchieri’s Festino, Children’s Music of Shakespeare’s Time, etc. And it’s not just the New York Pro Musica records made for the Expériences Anonymes or Esoteric labels. Even the recordings they made for the Columbia label—An Evening of Elizabethan Verse and its Music (with interspersed poetry readings by W.H. Auden) and the Monteverdi and Salamone Rossi albums—have somehow disappeared from the catalog. Even the NYPM’s several Decca recordings have disappeared, including the Play of Daniel that was once, briefly, reissued on an MCA twofer with The Play of Herod (sans Oberlin). I’ve since discovered that Amazon is selling it as an mp3 download only, no booklet or cover, for $1.79…but that’s not the same as being on a commercial CD.

Yet although one can sometimes question Greenberg’s arrangements for the group, there is nothing wrong with any of Oberlin’s recordings using a lute and/or harpsichord accompaniment, and there are many of them. Happily, a few of his finest moments on record have survived the cut and can be obtained on silver disc. Among the most priceless, in my view, are the following:

Handel Arias – Deutsche Grammophon 28947765417 – including a stunning version of “Vivi, tiranno!” (you can hear an abridged version of this recording here) from Rodelinda, then an oddity but today a well-performed opera, and an even more stunning two-and-a-half octave cadenza at the end of “Ombra cara” from the same opera)

Dowland: Lute Songs – Lyrichord LEMS8011 (no one has EVER sung these better, not in any voice category at any time in the history of recording)

Dowland: Lute Songs – Lyrichord LEMS8011 (no one has EVER sung these better, not in any voice category at any time in the history of recording)

Bach: Magnificat w/Lee Venora, sop; Jennie Tourel, mezzo; Charles Bressler, tenor; Norman Farrow, bass; Schola Cantorum; Leonard Bernstein, cond; New York Philharmonic Orchestra – Sony Classical 074646026120 (coupled with Eugene Ormandy’s performance of the Easter Oratorio)

Music of the Middle Ages, Vol. 4: English Polyphony of the 13th and Early 14th Centuries – Lyrichord LEMS8004 – here Oberlin is coupled by his old NYPM colleague, tenor Charles Bressler.

Purcell: Songs; Blow: Ode on the Death of Mr. Henry Purcell (with Charles Bressler, tenor) – VAI 1258. Possibly the greatest of all Oberlin albums. I’ve yet to hear any human voice sing the Purcell songs better…and remember, Purcell himself supposedly had a high “countertenor” voice like Oberlin himself. (Listen to his performance of “Music for a While” here.) And John Blow’s Ode on the Death of Mr. Henry Purcell is, for me, one of the greatest pieces of music ever written: not only well constructed but heartfelt and fascinating from first note to last. I guarantee that you will be mesmerized as soon as you hear Oberlin and Bressler start singing, “Mark, mark how the lark and linnet sing / With rival notes / They strain their warbling throats / To welcome in the spring.” In the 1970s, Murray Hill Records reissued this with the most God-awful phony stereo reverb you’ve ever heard in your life, completely distorting and ruining the sound, and this is how it is present on YouTube, so please…do yourself a favor and stay away. To compensate, for an extra-special treat, here is a link to a CBC television clip of Oberlin singing the Bach Cantata No. 54, “Widerstehe duch die Sünde,” with a small chamber orchestra led by Glenn Gould on the harpsichord.Of course, not everyone hears voices exactly the same way. There was a critic for Fanfare who, back in the 1980s, described Oberlin’s voice as sounding like Tiny Tim. I can only hope that he has met a suitable end to his poor hearing. If you approach Oberlin with an open mind, and open ears, I think you’ll be amazed. He was one of a kind. We will not hear his like again.

Update: Russell Oberlin has died on November 26, 2016.

—© 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Read my book: From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed history of the intersection of classical music and jazz

Wonderful article. Thank you!

LikeLike

Having sung counter tenor in various churches I was taken by Russel Oberlin@s

voice, I am now 86 and love to hear GOOD singing, I later became a Choirmaster

and ruined my voice by singing falsetto and I am afraid that I ruined my voice so much that I now find it difficult to sing at all.

LikeLike

So sorry to hear that! We have, sadly, lost or overlooked some very fine countertenors from the past such as David Schwartz and Richard Levitt.

LikeLike

I wholeheartedly agree. Russell Oberlin was a masterful singer and consummate musician; his Dowland Lute Songs is perhaps the finest of my personal desert island LPs. Unfortunately, I probably heard Oberlin live only once in The Play of Daniel, in Hartford, Connecticut.

Don’t forget that Oberlin’s partner on the Dowland album was another towering giant of early music: the magnificent lutenist Joseph Iadone. Iadone,first a jazz bass player, became a self-taught scholar of the lute and a prodigy nurtured personally by Paul Hindemith at Yale. Iadone was Oberlin’s equal on the lute, both performers exquisitely attuned to the meanings in Dowland’s poetry, which plumbs the depth of the human soul. At least once in one’s life, a person should be exposed to this recording. Iadone inspired many students at Hartford’s Hartt College of Music, where he taught for many years, and where I had the pleasure to hear him perform while I was a student there. With its wide fretboard, an authentic lute is not an easy instrument to master. Iadone played the lute with an unusual clarity, a clarity that exposed the subtle expressiveness of his phrasing; Iadone could even play very fast and yet always with a unique, subtle expressiveness that’s revealed on this recording.

Unfortunately, the Lyrichord CD, The Art of the Lute, is an awful legacy that one should be sure to skip. I suspect that Iadone’s health was failing when these tracks were recorded, probably never intended for formal release.

This Dowland LP, from about 1958, has been re-issued on a Lyrachord CD series, along with a number of other LPs from the EA record label. Unfortunately, the trailing echo of each selection is abruptly chopped off on these CDs. Otherwise, the sound is good and befitting to these marvelous artists. These recordings are worth hearing and enjoying; the Dowland is, I think, the best of them.

Richard Steinfeld

LikeLike

There really is no singer who is able to match the quality and power of James Bowman’s extraordinary voice. He has been the Gold Standard for many a year. Even Britten himself apologized to him for not using him on the krecording of A Midsummernight’s Dream. Since that time, during the Aldeburgh Festival premier of Death in Venice, Bowman remains the Gold Stndard. No one else compares.

LikeLike

If you’ve never heard Oberlin sing in person you really can’t comment. Even the British critics described Oberlin as the “trumpet among countertenors,” though of course that was before Bowman’s career, but I find it impossible to believe that someone singing in their natural voice would not be as loud as someone singing in falsetto. Nonetheless, Oberlin’s quality of voice is easily 10 times better than Bowman who, good musician though he is, is just another falsettist.

LikeLike