Neither audiences nor musicians—and certainly not music critics—ever really knew what to make of Spike Jones and his City Slickers other than that they were very funny, in fact over-the-top, maniacally funny. Despite their displaying an extremely high level of musicianship in their “crazy” playing, it was the end result that was judged and not the extraordinary technique and timing that went into their performances. Famed jazz trombonist Jack Teagarden, who once sat in with the band for a lark in a performance of Chloe, was paralyzed when the band arrived at the hyper-fast break in the middle of the song. Teagarden, reading from the score, couldn’t get more than one note out before the rest of the band had finished the break. He never underestimated the Slickers’ musicianship from that day forward.

Jones was originally a top studio drummer in the Los Angeles area, sitting in on numerous recording sessions as well as playing full-time in John Scott Trotter’s middle-of-the-road orchestra, the same band that backed Bing Crosby on both radio and records. Although Jones’ most famous session with Crosby was his 1942 recording of White Christmas, his drums can be heard to much greater advantage on Crosby’s 1937 recording of Mr. Crosby and Mr. Mercer, a comic duet with songwriter-singer Johnny Mercer. According to Jordan R. Young, the author of two definitive books on Jones, he enjoyed trying to create funny sounds on his drum kit even back then in his spare time.

On one recording session, Jones accompanied a popular vocal group called The Foursome and had a chat afterwards with one of the singers in that group, Del Porter, who also played clarinet. It turned out that Porter was getting sick and tired of performing the corny pop music of his day and had some ideas for lampooning them. Jones encouraged him to start his own band to vent his feelings, which he did, calling it The Feather Merchants. I don’t think the band ever recorded, but apparently they were well thought of in the L.A. area. The most popular “corny” band of the time was Freddy “Schnickelfritz” Fisher and his Orchestra, which also purposely played songs both popular and folk in a funny manner.

Jones began sitting in with Porter’s band, then became a full-time member while still fulfilling his studio gigs, and eventually took it over. The leadership move seemed inevitable and was done without rancor, since Porter was a laid-back, easy-going guy while Jones was a hyperactive idea man who seemed always to be operating in overdrive. He rarely slept or ate, living mostly on coffee and cigarettes, and was always trying to come up with new gag ideas as well as ways to promote and sell the band. In a late-1950s TV interview with Edward R. Murrow on his Person to Person show, Jones claimed that he got the idea for the Slickers after seeing Igor Stravinsky conduct one of his own pieces at the Hollywood Bowl, where he wore new shoes that creaked audibly every time he went up on tiptoe to emphasize a musical point. Although it was quite probable that Jones did see Stravinsky conduct, the full story just related is obviously closer to the truth.

As for where Jones got the idea for the band’s name from, this occurred in an early 1941 recording session for Standard Transcriptions with country singer Cindy Walker. The song they recorded that day was a Walker original, We’re Gonna Stomp Them City Slickers Down. Spike’s new band, still working as the Feather Merchants, accompanied her on that song, playing in the same style they would unveil in July of that year on their first recording session for RCA’s Bluebird label. Some of the musicians later verified that this is where Jones got the idea for the band’s name—though, of course, it was indeed already formed and performing.

Several of Jones’ early recordings showed a style that was not as complex as they later became but still far in advance of what Fisher was doing with his “Schnickelfritz” band, among them The Sheik of Araby, Siam, and Clink, Clink, Another Drink, on which they were able to feature a rising star in the cartoon industry, voice-over expert Mel Blanc. (Blanc was even featured with the Slickers in a “Soundie” made shortly after the release of the record, a rare early example of an artist using video to help sell an audio recording.) But of course, the record that put him on the map was made in 1942, and that was Der Fuehrer’s Face. In today’s world, this song sounds relatively tame (especially when compared to some of Jones’ incredibly complex arrangements from 1944 onward), but in its day it created a sensation, particularly when “Willie Spicer” (actually, Jones himself) played the “Birdaphone”—a rubber razzer—every time the band shouted out “HEIL!” RCA, in fact, was so worried about a negative reception that they forced Jones to record an alternate take using a trombone in place of the raspberry, but fortunately they eventually chose to release the take with Spicer giving Hitler the Bronx cheer. (After hearing the record, Spike Jones went to the top of Hitler’s enemies list. It’s a good thing for Spike that his USO tours with the band provided plenty of security.)

As in the case of every orchestra then performing, including the serious jazz bands, at least 14 months were lost due to the Musicians’ Union’s strike against the record companies. Decca and Capitol, the youngest of the major labels (founded in 1934 and 1942 respectively), were the first to sign, restarting their recording activities in November 1943, but RCA and Columbia, both industry giants, didn’t settle until around mid-1944. Fortunately, thanks to the Slickers’ newfound popularity, there are tons of broadcast recordings from that period available. Some of them are very funny, particularly As Time Goes By, It Never Rains in Sunny California, The Trolley Song, I Want a Gal and He Broke My Heart in Three Places, some of them featuring a singing duo called the Nilsson Twins who would later become better known singing “straight” pop tunes, but many were just mildly humorous in the vein of Behind Those Swinging Doors. The best of these songs were The Great Big Saw Came Nearer and Nearer and a real gem, Never Hit Your Grandma With a Shovel (It Makes a Bad Impression on Her Mind), never recorded commercially by Jones although it was recorded, at a faster tempo and without much humor in the singing, by some Country guy named Dick Unteed. Yet it is the Jones version which everyone remembers and plays, and somehow the song made it into the underbelly of popular culture. (Tiny Tim sang the first two lines on his debut album.)

The radio broadcasts also show how the band was evolving in 1943 and early ’44. Two major acquisitions during this period were saxophonist and comic vocalist Ernest “Red” Ingle, who had formerly worked for Ted Weems and later formed his own comedy band, The Natural Seven, and trumpet player George Rock, who Jones snagged from Freddy Fisher’s band. Rock was a virtuoso of his instrument, no joke; he could play anything from jazz to classical in its correct configuration, including outstanding double- and triple-tonguing (which you can hear on his “straight” performance of Minka), in addition to being able to imitate virtually every famous jazz or pop trumpeter in the business from Louis Armstrong to Harry James, Clyde McCoy and Charlie Spivak. For years a rumor circulated that Rock had played for a year with Charlie Barnet’s famous jazz orchestra, but this turned out to be a myth. He started with Fisher in the late 1930s (heard to best advantage on Fisher’s recording of Turkey in the Straw), and there he stayed until Spike took him into the fold around late 1943.

Jones’ hyperactive mind and strong intuitive sense of promotion was leading him to create more and more complex arrangements, some of them written by Joe “Country” Washburne, tuba player extraordinaire, who had also been in the Weems band with Ingle but left Spike because he detested air travel. It was an amicable split, however, as were most of those who left the Jones band; the only two exceptions were vocalist Carl Grayson, the master of “glugs,” who was eventually fired by Jones because he was a serious alcoholic who was not reliable in showing up for performance (or being able to perform because he was so inebriated), and Grayson’s successor, Mickey Katz, who walked out on Jones because he felt he wasn’t being paid enough for his talents. Katz, like Ingle, also formed his own comic band, but Katz went even further, modeling his “Kosher Jammers” directly on the kind of sounds that Jones brought out of the City Slickers—omitting only the bulb horns and pistol shots.

As I say, however, Jones’ approach to “musical depreciation” was a much visual as it was aural, and fortunately there are several videos from different periods in the band’s history that show how his visual approach evolved. He always timed the sight gags with the aural ones, but as time went on, both became much more complex.

First, here is the video of the band in 1941, their first year in the “big time,” doing the hillbilly spoof Pass the Biscuits, Mirandy—funny, but visually rather minimal. Then there are two videos of the band doing their wacky arrangement of Hotcha Cornia (Otchi Chornya), one from the Eddie Cantor film Thank Your Lucky Stars and the other from a live performance at a naval base, the second showing how it was done when they really didn’t have the stage room to run around. (Yes, there’s also a video of them doing Der Fuehrer’s Face, but it’s pretty tame, just Spike and Carl Grayson in close-up with no shots of the band.) Next we get the video version of their biggest-selling record, Cocktails for Two. By this time, George Rock was playing trumpet with the band, but they still hadn’t started wearing their crazy plaid and/or checkered suits—everyone was still dressed pretty normally. (But this film clip does capture Carl Grayson doing his famous glugs along with Spike and another band member, and there’s a cute gag near the end where the band is swaying in one direction while Spike, leading them, is swaying in the opposite direction.

By the time they did Chloe in 1946, things were definitely getting crazier. Spike, at least, is wearing a suit with a small checkered pattern, and the whole props-and-gimmicks department surrounding Red Ingle’s vocal is already starting to resemble the shows of his nuttiest years. The band’s performance is also looking looser and more natural. From here we can jump to any number of his 1951-54 television appearances, by which time the act had become so raucous and complex that if you blinked, you missed something—usually something funny.

A 1951 publicity photo – staged, not natural – of the City Slickers to promote their TV show. Top row: Sir Frederic Gas (Earl Bennett) playing his “tree branch” violin, unknown tuba player, Jack Golly on clarinet, Doodles Weaver pretending to play saxophone, unknown saxist, drummer Joe Siracusa “playing” a baseball bat. Bottom row: trumpet virtuoso George Rock, comedian Dick Morgan on banjo, Spike, comedian-banjo virtuoso Freddy Morgan, unknown.

Also by 1946, as one can hear in Cocktails for Two, Love in Bloom and I’m Getting Sentimental Over You, the “serious” introductions to these songs were played on as high a level as any legitimate band in the nation. Proud of what he had accomplished, Jones tried to capitalize on this by turning that segment of his band into the “Other Orchestra,” which didn’t play funny at all. He spent a small fortune out of his own pocket for two years trying to make the Other Orchestra a success, but to no avail. It died a horrible death, leaving him in debt to some of the musicians. The reason was not just that the Other Orchestra wasn’t the City Slickers. Its problem was that the arrangements it played were very good but had nothing interesting or individual about them. For better or worse, even the “Mickey Mouse” bands of Sammy Kaye and Shep Fields had a distinctive style all their own. The Other Orchestra sounded no different from the very generic orchestras of arrangers like David Rose or Axel Stordahl. Had Spike put as much imagination into the Other Orchestra’s arrangements as he did into the Slickers, creating a style that was new and ear-catching, it might have caught on, but for whatever reason he didn’t.

A more realistic picture ofthe Slickerws in action, this time with Siracusa on drums (Spike played washboard, cowbells, and his “noise rack” with the band).

Although Jones’ second wife, singer Helen Grayco, later said that Spike’s TV show years were his happiest—and they may well have been—it was actually his half-hour Coca-Cola-sponsored radio show of 1947-49 that presented the band in its best balance between serious and crazy. In the first year, his wife occasionally appeared as a gust singer, but for the last two years Jones’ co- host was Dorothy Shay, the “Park Avenue Hillbilly,” who had a pleasant voice and wrote several funny songs (but not crazy, “Spiked”-up ones) for herself. The format would run like this: Spoken intro over seriously-played theme music, a crazy number by the Slickers (often with a gag thrown in between Spike and some of the band members), then perhaps a short comedy routine with Dick Morgan, George Rock or Sir Frederic Gas (Earl Bennett). Then Shay would be introduced, exchange a little banter with Jones, and sing one of her songs. This would be followed by one more crazy number by the Slickers, then an ad break for Coke. After the break, the weekly guest star would be introduced—usually a popular singer or comedian but sometimes a famous film star. After a little banter, the guest singer would do a song straight, usually one of their recent hits (among his guests were Mel Tormé, Frank Sinatra and the tragically short-lived Buddy Clark). Then Doodles Weaver would do one of his confused-spoonerism song parodies. It’s absolutely amazing how many of these Weaver was able to come up with, a new song almost every week, and none of them made it to a record except for The Man on the Flying Trapeze.

host was Dorothy Shay, the “Park Avenue Hillbilly,” who had a pleasant voice and wrote several funny songs (but not crazy, “Spiked”-up ones) for herself. The format would run like this: Spoken intro over seriously-played theme music, a crazy number by the Slickers (often with a gag thrown in between Spike and some of the band members), then perhaps a short comedy routine with Dick Morgan, George Rock or Sir Frederic Gas (Earl Bennett). Then Shay would be introduced, exchange a little banter with Jones, and sing one of her songs. This would be followed by one more crazy number by the Slickers, then an ad break for Coke. After the break, the weekly guest star would be introduced—usually a popular singer or comedian but sometimes a famous film star. After a little banter, the guest singer would do a song straight, usually one of their recent hits (among his guests were Mel Tormé, Frank Sinatra and the tragically short-lived Buddy Clark). Then Doodles Weaver would do one of his confused-spoonerism song parodies. It’s absolutely amazing how many of these Weaver was able to come up with, a new song almost every week, and none of them made it to a record except for The Man on the Flying Trapeze.

If the guest star was a comedian or actor, he or she would be introduced and do a little routine with Spike and possibly with Dorothy as well. Somewhere in the mix the Slickers would play another crazy tune, then sign-off and theme. If the guest was a singer, Spike would do a medley based on a theme: “dream” songs or “home” songs or songs with a Western slant, whatever. Shay would sing the opening song, the guest star would do the second, then the Slickers would tear it up for the finale. The show was so popular, in fact, that it was given the coveted half-hour before the immensely popular Jack Benny Program.

As I noted earlier, throughout the City Slickers’ history, neither RCA nor the public could quite figure out if its crazy antics appealed more to adults or to children. It’s clear that his 1946 expanded version of the Nutcracker Suite was aimed for kiddies, with a chorus singing about sugar-plum land etc., and indeed that album was a favorite with tots, but his inspired-yet-vicious lampooning of Tchaikovsky’s “characteristic dances,” Waltz of the Flowers excepted, were clearly appreciated as much if not more by adults and particularly by fellow musicians. Indeed, it would be good for one to really listen to these arrangements carefully and try to pick apart their components without laughing too hard. It’s difficult because everything moves so quickly, but the closer you listen the more you come to appreciate the genius—and that is the right word for it—that he and his arrangers poured into their crazy concoctions. It not only takes a sharp ear to make out everything they play, particularly when they’re going at warp speed, but if you’re a professional musician just try imagining trying to play these “crazy” arrangements at that speed with that kind of precision. It’s almost like trying to repair a race car while it’s still moving.

And if you don’t want to take my work for it, just ask Peter Schickele. He based his crazy fictional composer P.D.Q. Bach on Jones’ classical lampoons, yet despite a half-century of trying, he never once was able to exactly replicate the kind of musical mayhem that the City Slickers exhibited. In fact, no one has. Many have tried, including his own son Spike Jr. and Richard Carpenter (yes, even the Carpenters tried to do a Spike Jones imitation on their TV show!), but none have ever succeeded. What he did was, quite simply beyond imitation.

There are so many excellent City Slickers recordings that it would be futile to describe them all in detail, but if I had to pick just one to show how brilliant this man and his band could be, it would be his 12-minute “deconstruction” of Bizet’s opera Carmen. Recorded in 1949 when the Slickers were at their very peak, it is both very funny and absolutely virtuosic. Eddie Brandt’s highly imaginative arrangement even went so far as to score the virtuosic “Gypsy dance” at the beginning of Act II for the 12 musicians in the City Slickers—and they played it without a hitch. Take that, Freddy Fisher!

There’s a certain irony in the fact that although Jones’ band was finally heard and seen to its best advantage on his early-‘50s TV show, this is exactly the period when RCA Victor started pushing and not just suggesting more and more childish songs and arrangements. While Spike was still turning out such inspired arrangements as Deep Purple, Pal-Yat-Chee, Dragnet, I’m in the Mood for Love and others, RCA insisted on recording a string of little kid songs with George Rock doing his little kid voice. They even forced Jones to do one of them, I’m the Captain of the Space Ship, on his TV show, much to Spike’s resentment. His brilliant 1952 recording of I Went to Your Wedding, for instance, had a very brief lifespan on American RCA; it stayed in print much longer on the British HMV label. Eventually, by 1955, Spike had enough and cut ties with the label that had nurtured and promoted him since 1941, telling the press, “I was an RCA victim.”

Shortly after leaving RCA, Jones recorded a funny spoof of Perez Prado’s Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White, which RCA had forbade him to do, on the tiny Spotlite label as “Davey Crackpot and his Musical Jumping Beans.” It’s a dead giveaway that the record is by Spike since Cherry Pink lists George Rock’s name on the label as trumpet player and the flip side, No Boom-Boom in Yucca Flats, features a vocal by Billy Barty. Yet to my knowledge, no one except me has ever put either side in a Spike Jones collection.

In 1956, Jones signed a short-term deal with, believe it or not, Norman Granz’ Verve label. Verve was specifically dedicated to jazz performances, particularly three of Granz’ favorite musicians, Ella Fitzgerald, Art Tatum and Dizzy Gillespie, but suddenly here was Spike Jones with a new 10” single featuring four songs (two on each side): Love and Marriage, The Trouble With Pasquale, Memories Are Made of This (the first “barking dog” record) and 16 Tacos. The following year, Verve released the City Slickers’ only album in hi-fi and, as it turned out, their very last as a group, Dinner Music for People Who Aren’t Very Hungry. Again there were a couple of songs on it that clearly appealed to kids, particularly the very dumb Wyatt Earp Just Makes Me Burp, but also some tracks that were devastatingly funny even to adults. Jones re-used Memories Are Made of This on this LP, which also included the first-ever releases of his radio transcription recordings from 1943-44 of Cocktails for Two and Chloe. It sold enough copies for Granz to break even, but not many more. Clearly, the Slickers’ day in the sun was over.

In 1958 Spike reappeared on TV, this time wearing a tux and white tie instead of his checkerboard suits and with a band that played relatively straight even when he did spoofs like Indian Love Call with soprano Mimi Benzell. I remember watching that program with my parents. I found it pretty funny, but was assured that he was much funnier earlier on. A year later, my Uncle John gave me his copy of Jones’ Liberty LP, Omnibust, saying that he was disappointed because there wasn’t much of the “real” Spike Jones band on it. And indeed there wasn’t, except for a wild one-minute version of Les Baxter’s Quiet Village (a hit at the time for Martin Denny). But I did like Loretta’s Soaperetta, Ah-1, Ah-2, Sunset Strip, I Search for Golden Adventure in my Seven Leaky Boots and a spoof of the Kentucky Derby, even though I later discovered that all but the second of these were watered-down versions of earlier records.

In 1960, when I was nine years old, I finally heard the “real” Spike Jones band…in my Catholic grammar school! One of the nuns gathered all three fifth grade classes into one classroom and played us Spike’s 78 record of Happy New Year. I never laughed so hard in all my life up to that time. A year later, I saved up my allowance (25¢ a week, folks…that’s all my parents would give me) until I could afford to buy a copy of Thank You, Music Lovers!, the RCA Victor album that presented 12 of Spike’s biggest sellers and funniest hits. That’s when I learned how good and how original this band really was…and I also found out that None But the Lonely Heart became Loretta’s Soaperetta and William Tell Overture became the Kentucky Derby spoof. (It wasn’t until years later that I ran across a 78 of Down in Jungle Town to find the original source of Seven Leaky Boots.) I was hooked. I bought every Spike Jones 78 I could find, years before most of them (but certainly not all) were reissued on LP and later on CD.

But by then, Spike had moved on to other projects. One was an excellent spoof of idiotic novelty songs from the past in an album titled 60 Years of Music America Hates Best; another was an unfortunately very childish album of Halloween nonsense, A Spike Jones Spooktacular. Then he gave up funny music altogether, creating a sort of Dixieland-meets-folk-music group to record such things as Washington Square, an album of Hank Williams tunes, and novelty instrumentals like Powerhouse and Frantic Freeway.

He was clearly past his prime, and not just artistically. Decades of chain-smoking had ruined his health, given him COPD and confined him to a wheelchair with an oxygen tank when he wasn’t performing. Then, in 1964, he and eight of the City Slickers (including George Rock, Freddy Morgan and Joe Siracusa) made a surprise TV appearance on which they played spirited versions of Ketelbey’s In a Persian Market and Khachaturian’s Sabre Dance. It was the last time that Jones “Spiked” the classics and truly the last gasp for the Slickers.

Spike and the City Slickers in 1964

Sadly, I never saw that last TV appearance of the Slickers, but I did see him play a sleazy lawyer on the Burke’s Law program in early 1965. Then, on May 2, 1965, while doing my paper route, I glanced at the front page of the paper and learned that Spike Jones had died the day before at age 53. I was shocked and heartbroken. No one else I knew cared, but I knew that the world had lost a musical comedy genius.

For those of you who haven’t really explored Spike Jones in depth, or for those of you who have been looking for some of his rarest recordings for years without being able to find them, I can recommend three uploads on the Internet Archive.

Thank You, Music Lovers. This album was originally released with this wonderful cover art by Jack Davis in 1960 in mono, then reissued in electronically-enhanced “stereo” in 1967 as The Best of Spike Jones and his City Slickers. Adopting the expanded format of RCA’s “Vintage Series” albums, however, I have added six excellent tracks not on the original album.

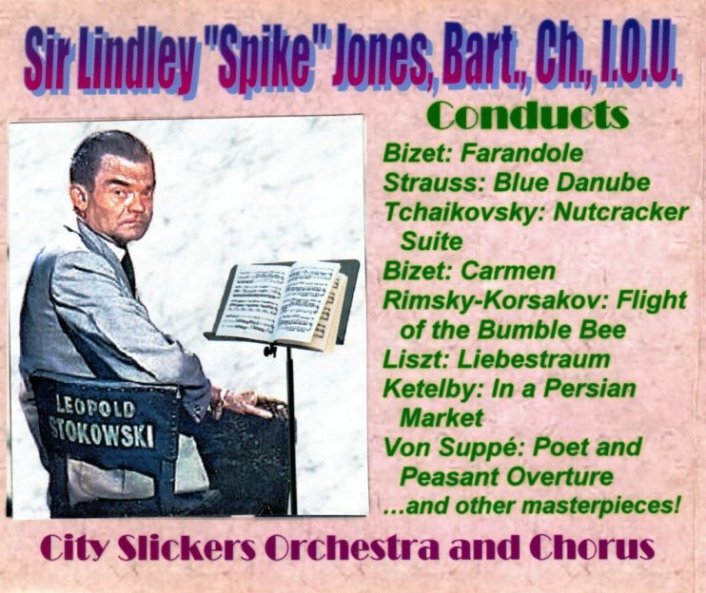

Sir Lindley “Spike” Jones, Bart., Ch., I.O.U, Conducts. I created this 4-CD set myself from some of Spike’s rarest broadcasts, studio recordings and TV clips, including the complete Poet and Peasant Overture. In all but a very few cases, I was able to track down the original mono pressings rather than the botched “electronic stereo” versions that circulated in the U.S. for many years.

Dinner Music for People Who Aren’t Very Hungry. Recorded and released in 1957, Dinner Music for People Who Aren’t Very Hungry was Spike Jones’ first high-fidelity album as well as the last for the City Slickers. It included the first issues ever of Jones’ original broadcast performances of “Cocktails for Two” and “Chloe,” made well before their studio recordings, thus we get vocals here by two band members who were long gone by 1957, Carl Grayson and Red Ingle. I am particularly fond of this version of “Pal-Yat-Chee,” which features a vocal by Betsy Gay, the “confused coloratura,” who does a splendid job alternating between a “hillbilly” voice and one that sounds like a trained soprano.

Two bonus tracks are included here, “Mairzy Doats” from Spike’s 1960 album 60 Years of Music America Hates Best and “Frantic Freeway,” a 1962 recording in which Jones experimented with instrumental and sound effects overdubbing.

And that, as they say, is that. I sincerely hope that you love these recordings as much as I do. Unlike most comedy records, re-listening to Spike Jones often reveals details you might have missed the first (or second, or third) time you heard it, thus they are among the very few comedy recordings worth keeping in your collection.

—© 2023 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter or Facebook

Check out the books on my blog…they’re worth reading, trust me!

Pingback: The King of Musical Mayhem – MobsterTiger

When I was a kid in the 40s l oved Spike Jones music items on radio especially Poet and Peasant overture How he made the classics palatable even to non-musicians . I still have a cd with many of his selections including Beedlebaum I have a cd with several selections including Poet and Peasant as well as William Tell overtures and of course, Beedlebaum Thank you informing the world of this forgotten gem of musical gifts. Augusta Sent from Mailhttps://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?LinkId=550986 for Windows

LikeLike