In an era when atonal, serial, quarter-tone and microtonal classical music is taken for granted, the earliest and (in my opinion) greatest such composer of all is not only virtually forgotten but consistently ignored. His name was Julián Carrillo Trujillo, he was born in 1875 and lived into his 90th year, and he did far more to promote microtonal music than all the others who followed him combined.

In an era when atonal, serial, quarter-tone and microtonal classical music is taken for granted, the earliest and (in my opinion) greatest such composer of all is not only virtually forgotten but consistently ignored. His name was Julián Carrillo Trujillo, he was born in 1875 and lived into his 90th year, and he did far more to promote microtonal music than all the others who followed him combined.

So how did I run across him? You’re not going to believe this, but it was from a friend of mine, a member of the Vocal Record Collectors’ Society. The reason I say you won’t believe it is that he, like most of the members of the VRCS, can’t stomach music of this sort and considers it “non-music.” They enjoy operas of the tonal school, with tunes and lots of high notes, and that’s it. He has 265 recordings of Puccini’s Tosca but still can’t understand or appreciate Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande (“it’s all murk”) and stays as far away from the operas of Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg as possible.

But he does get the regular 78-rpm catalogs from vintage-record dealer Lawrence Holdridge, and he was kind enough to pass one along to me. And there, in Holdridge’s latest catalog, was listed a copy of Carrillo’s 1930 Columbia recording of the microtonal Preludio a Cristobal Colon (click on titles to pull up YouTube videos). This recording is remarkable not only because of its experimental nature, in which the soprano voice and instruments slither through gradations of microtones with insouciant ease, but absolutely none of the amazing musicians—not even the singer!—are identified on the record label, and even Holdridge’s thousands of contacts in the music world were not able to come up with a single performer’s name. Only the director of the ensemble, one Angel Reyes, is named. And despite the strangeness of the music, this disc stayed in the Columbia catalog (with two number changes) at least up through 1949.

But he does get the regular 78-rpm catalogs from vintage-record dealer Lawrence Holdridge, and he was kind enough to pass one along to me. And there, in Holdridge’s latest catalog, was listed a copy of Carrillo’s 1930 Columbia recording of the microtonal Preludio a Cristobal Colon (click on titles to pull up YouTube videos). This recording is remarkable not only because of its experimental nature, in which the soprano voice and instruments slither through gradations of microtones with insouciant ease, but absolutely none of the amazing musicians—not even the singer!—are identified on the record label, and even Holdridge’s thousands of contacts in the music world were not able to come up with a single performer’s name. Only the director of the ensemble, one Angel Reyes, is named. And despite the strangeness of the music, this disc stayed in the Columbia catalog (with two number changes) at least up through 1949.

Listening to this recording online, I was utterly fascinated, and the reason I was so entranced was that despite the experimental nature of the piece it was still MUSIC. It had a melody of sorts; it had a beginning, a middle, and an ending. It was well-constructed and it developed. In this sense, it had very little in common with the later pieces of such similar composers as Giacinto Scelsi and György Ligeti, which moved the harmony and rhythm along with the top line. Carrillo’s music had a firm grounding in proper classical principles and an emotional appeal quite different from those who followed in his footsteps.

This led me to delve further into the man and his music. As it turned out, he was a poor Mexican, born in Ahualulco, a village in San Luis Potosi, the last of 19 children. His rise in the musical world was entirely the gift of “angels” who saw in him a potentially great musician. To quote Wikipedia:

While singing in the children’s choir of the local church, choir director Flavio F. Carlos encouraged him to study music in the state capital. He planned to study for two years, then return to Ahualulco as the church’s singer, but problems prevented this plan. He arrived to San Luis Potosí City in 1885 and began to study with Flavio F. Carlos, teacher to several generations of San Luis Potosí’s composers. Carrillo also began to work in his teacher’s orchestra where he was a percussionist and later, violinist.

He composed his first small works for this group. Because of the economic situation of his family, Carrillo left his primary school studies early, but continued working in the orchestra and studying music with Carlos. In 1894, Carrillo composed a mass that was locally successful. This, along with a letter of recommendation from the government of San Luis Potosí, allowed him to go to study in the National Conservatory of Music in Mexico City. Carrillo made quick progress in the Conservatory. His professors included Pedro Manzano (violin), Melesio Morales (composition), and Francisco Ortega y Fonseca (physics, acoustics, and mathematics).

Having not completed primary studies, he was ignorant of the acoustic basis of music—so he was fascinated when Ortega discussed laws governing (the) generation of fundamental intervals in music. For example, when a violin string is depressed (stopped) at its midpoint, it produces a pitch twice the frequency of (an octave above) the open string. When a string is stopped at one-third, the remaining two-thirds vibrates a perfect fifth higher than the open string (almost exactly equivalent to 5/8 of an octave). Carrillo explored these relationships in experiments. For a while he tried, but couldn’t divide the string further than into eight equal parts. Then he left the traditional way of dividing the string into two, three, four, five, six, seven and eight equal parts, and, using a razor to stop the string, divided the fourth string of his violin between G and A into sixteen parts. He could produce sixteen clearly different sounds within a whole tone.

From then on, he immersed himself in the study of the physical and mathematical basis of music. In 1899, General Porfirio Díaz, President of Mexico, heard Carrillo as a violinist. Díaz was impressed, and gave him a special scholarship to study in Europe.

Carrillo was admitted to the Leipzig Royal Conservatory, where he studied with Hans Becker (violin), Johann Merkel (piano), and Salomon Jadassohn (composition, harmony and counterpoint). He became first violin in two orchestras: the Conservatory’s Orchestra, conducted by Hans Sitt; and the Gewandhaus Orchestra, conducted by Arthur Nikisch. Carrillo composed several works at Leipzig, including Sextet in G Major for two violins, two violas and two violoncellos (1900), and the First Symphony in D Major for Orchestra (1901). Carrillo conducted the Leipzig Royal Conservatory Orchestra in the premiere performance of his First Symphony.

Carrillo was admitted to the Leipzig Royal Conservatory, where he studied with Hans Becker (violin), Johann Merkel (piano), and Salomon Jadassohn (composition, harmony and counterpoint). He became first violin in two orchestras: the Conservatory’s Orchestra, conducted by Hans Sitt; and the Gewandhaus Orchestra, conducted by Arthur Nikisch. Carrillo composed several works at Leipzig, including Sextet in G Major for two violins, two violas and two violoncellos (1900), and the First Symphony in D Major for Orchestra (1901). Carrillo conducted the Leipzig Royal Conservatory Orchestra in the premiere performance of his First Symphony.

In 1900, Carrillo attended the International Congress of Music in Paris, presided by Camille Saint-Saëns. He presented a paper, which the Congress accepted and published, on the names of musical sounds. He proposed that, since each note is one sound, each note name (C, D flat, etc.) should be a single syllable. He proposed 35 monosyllabic names. He also befriended Romain Rolland. When he finished his studies in the Leipzig Conservatory, he went to Belgium to improve his skills as a violinist. There, he studied with Hans Zimmer (who had been Eugène Ysaÿe’s student) and was admitted to the Ghent Royal Conservatory of Music. In 1903, he composed a Quartet in E minor, which he intended to give, “ideological unity, [and] tonal variety,” to classical forms.

In 1904, he won the First Award Cum Laud and with Distinction in the Ghent Conservatory International Violin Competition. Later that year he returned to Mexico where President Díaz gave him an Amati violin “as a present from the Mexican Nation” for his excellent performance in foreign countries. In Mexico City, Carrillo began intense work as violinist, orchestra conductor, composer and teacher. He was appointed professor of history (1906), composition, counterpoint, fugue and orchestration in 1908 by the National Conservatory. Among his students was José Francisco Vázquez Cano who founded the Free School of Music and Declamation, the Faculty of Music of the National University (UNAM) and the National University Philharmonic Orchestra (OFUNAM).

When Victoriano Huerta’s government was overthrown, Carrillo had to flee to the United States. In New York City, he organized and conducted the American Symphony Orchestra. He performed his First Symphony in New York. The success of this work was so great that a journalist named him “the herald of a musical Monroe Doctrine”. In 1916, Carrillo composed music for D.W. Griffith’s film, Intolerance. In New York, Carrillo also wrote the “Thirteenth Sound Theory” which was published later in the second volume of Musical Talks.

In 1918, he came back to Mexico, where he was chosen to conduct the National Symphony Orchestra (1918–1924) which had been the Conservatory’s Orchestra. He was also named Principal of the National Conservatory (1920–1921). Carrillo led the National Symphony Orchestra to performance excellence. Renowned pianist Leopold Godowsky said the orchestra was superior to the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. The National Symphony Orchestra was so popular, it could be sustained by its own economic resources. With his orchestra, Carrillo introduced Mexico to the music of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Weber, Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Richard Strauss, Saint-Saëns, Debussy and Ravel.

Believe me, you had to be a great violinist to be picked for the first chair in an orchestra led by Artur Nikisch. Nikisch was, by universal opinion, the greatest conductor of his time. And it was in the late 1910s, immediately after the First World War, that he began to develop his microtonal theory which he called “Sonido 13” or “The 13th Sound” in order to distinguish it from Arnold Schoenberg’s 12-tone technique. As we all know, Schoenberg’s approach to splitting the musical atom was to take the 12 half-tones in an octave and decree that when composing music you must use each of those 12 tones at least once before you can repeat any of them. This led to some interesting experiments, such as the still-startling Pierrot Lunaire and the one-woman opera Erwärtung, but it also boxed composers into a corner. Yet because Schoenberg fled to the United States to escape Nazi persecution, he became immensely influential in this country, and after World War II he spawned a large movement of composers who believed that his approach was the only proper one to apply to modern classical music. Anyone who wrote in a tonal idiom was ridiculed and ostracized, and after Schoenberg’s death in 1951 even Igor Stravinsky threw over his own neo-Classical style to embrace the Schoenbergian aesthetic.

Now, there were some truly great and remarkable works composed in that idiom, but as I suggested earlier, it was a limited and restricted format that eventually became a maze with no outlet for creativity. Thus we had the rise of such microtonal composers as Scelsi, Ligeti and Penderecki, who then influenced composers of their generation. Yet meanwhile, through all of this period, Carrillo just kept chugging along, writing his microtonal music for a wide variety of instruments. String and wind instruments, of course, could slither through microtones, although they had to have exceptionally keen ears to hear the differences. In order to enable others to participate in his music, Carrillo developed the microtonal piano and microtonal harps, long before anyone else even though of them.

An example of Carrillo’s personal notation system (unexplained online)

Needless to say, he met with resistance, but oddly enough this resistance came not just from composers who still worked within the well-tempered system but also from other avant-garde composers in Western Europe. Jealous of his brilliance, they complained that it was “impossible to perceive such little intervals,” and when Carrillo proved that even lay listeners with a decent sense of pitch could indeed perceive them, they complained that he “stole” his ideas from German composers. I will say right here and now that this was nothing more than racism. Because Carrillo was a Mexican, and therefore looked down on even by Spaniards, their goal was to belittle and marginalize him and his music, and to a large extent they succeeded. Only in America was his work taken seriously, at least for a little while. His Sonata casi fantasia in quarter-, eighth- and sixteenth-tones was premiered in New York’s Town Hall in March 1926. Impressed by this work, Leopold Stokowski commissioned a Concertino which he premiered with the Philadelphia Orchestra a year later. This is undoubtedly what led to Columbia Records issuing his Preludio a Cristobal Colon in 1930—as it turned out, the first and last recording of his music to appear for 30 years!

Oscar Vargas Leal, David Espejo y Avillas and their microtonal harps

Around the time of the Concertino’s premiere, Carrillo wrote his Leyes de Metamórfosis Musicales (Musical Metamorphosis Laws), a method to transform the tonal proportions of a work. For example, half tones become whole tones and whole tones become double tones; or half tones become quarter tones and quarters become eighths, and so on. In addition, these laws present a compositional process similar to serialism. He also wrote Pre-Sonido 13: Rectificación básica al sistema musical clásico—Análisis físico musical (Pre-Thirteenth Sound: Essential Rectification to classical musical system—Physical musical analysis) and Teoría lógica de la música (Logical Theory of Music). The Mexican government honored him for his work, but he didn’t receive a dime of support from them or anyone else. Opponents put obstacles in his way as a conductor and professor of music. After that, he rarely was invited to conduct in Mexico and his music was seldom performed. Despite being former Principal of the National Musical Conservatory and titular Conductor of the National Symphony, he never obtained similar jobs again despite his abilities and decades of experience. He had to pay for his own musical research, making musical instruments, publishing his compositions, etc.

Yet he continued to write new compositions and, occasionally, get them performed. A small glimmer of light in this musical darkness came in New York in 1947 where he conducted experiments at the city’s University disproving the then-prevalent “node law.” Carrillo showed that it had to be modified since a node is not a mathematical point but a physical one, i.e., if a violin string is stopped below halfway, the frequency of the bowed fraction is more than twice the frequency of its base note.

Then, suddenly, the world of modern music opened its doors to him. In the late 1940s he gave lectures in France, Spain and Belgium. In 1951 Stokowski again conducted one of his works, the astounding Horizontes, a symphonic poem for violin, cello and microtonal harp, and the reception was so successful that the concert had to be repeated. In 1952 Stokowski played this work in in Minneapolis, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. In 1954 Carrillo donated a metamorphoser piano in third-tones to the Schola Cantorum in Paris; two years later, President René Coty, who preceded Charles de Gaulle, named Carrillo a Knight of the Legion of Honor. This was followed by West Germany giving him the Great Cross of the Order of Merit, and in 1958 Carrillo won a gold medal at the Brussels World Exposition for his 15 metamorphoser pianos.

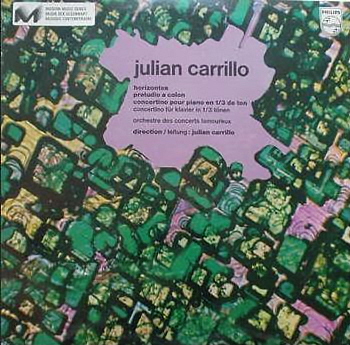

Now flush with honors and, more importantly, much-needed money, Carrillo was finally able to get the bulk of his music recorded. Starting in 1960, at the age of 85(!), he began an astonishing series of stereo LPs made in Paris with the Concerts de Lamoureaux Orchestra, which he himself conducted. Although made under the auspices of the Dutch record company Philips, they only released a few of them on their label; most were issued on Carrillo’s own “Sonido 13” and Universidad Nacional Ajutonama di Mexico (UNAM) labels. Here he was able to work with the outstanding musicians of the Quatuor Villers, violinists Francine Villers and Nicole Lepinte, violist Marie-Thérèse Chaillet and cellist Reine Flachot, as well as with such top-notch soloists as violinist Robert Gendre and Gabrielle Devries, pianist Bernard Flavigny and the world-renowned flautist Jean-Pierre Rampal. His amazing Mass for Pope John XXIII in quarter tones (1962, available in five parts beginning here) was recorded by the only French chorus that could sing it, a group made up of professors from the Paris Conservatoire; this album was later reissued in 1969 by CRI in their “New World” series. His last completed composition was Balbuceos (Babbling) for metamorphoser piano and orchestra, premiered once again in America by Stokowski in 1965. He died in September of that year, aged 90.

Now flush with honors and, more importantly, much-needed money, Carrillo was finally able to get the bulk of his music recorded. Starting in 1960, at the age of 85(!), he began an astonishing series of stereo LPs made in Paris with the Concerts de Lamoureaux Orchestra, which he himself conducted. Although made under the auspices of the Dutch record company Philips, they only released a few of them on their label; most were issued on Carrillo’s own “Sonido 13” and Universidad Nacional Ajutonama di Mexico (UNAM) labels. Here he was able to work with the outstanding musicians of the Quatuor Villers, violinists Francine Villers and Nicole Lepinte, violist Marie-Thérèse Chaillet and cellist Reine Flachot, as well as with such top-notch soloists as violinist Robert Gendre and Gabrielle Devries, pianist Bernard Flavigny and the world-renowned flautist Jean-Pierre Rampal. His amazing Mass for Pope John XXIII in quarter tones (1962, available in five parts beginning here) was recorded by the only French chorus that could sing it, a group made up of professors from the Paris Conservatoire; this album was later reissued in 1969 by CRI in their “New World” series. His last completed composition was Balbuceos (Babbling) for metamorphoser piano and orchestra, premiered once again in America by Stokowski in 1965. He died in September of that year, aged 90.

And his music once again fell into a black hole.

Yet there is much of it available on YouTube, taken from old and sometimes scratchy LPs; only the Mass for Pope John XXIII seems to be available in pristine condition. Sadly, his great Violin Concerto, played by Gendre, only has the first movement available, but all the others seem to be complete (although the great, massive Triple Concerto cuts off in the middle of a chord). It is all worth your while to hear, and you will note that Carrillo was not so dogmatic that he wrote everything in quarter or microtones. His Violin Sonata No. 1 (1939), dedicated to Paganini, is more tonal than usual, as are the Cello Concerto (played beautifully by Flachot), the Triple Concerto and some of the Piano Preludes. Sometime during his later period, he also rescored the Preludio a Colon for soprano and strings, and this recording, too, is available online. For your edification, I have copied and uploaded the first page of the Preludio a Colon as well as a few pages of the Gloria from the Mass for Pope John XXII. They bear close study.

Cover of Philips LP 832 272 DSY, which included Horiaontes, Preludio a Colon and the Concertino for piano in 1/3 tones

The point I am making is that Julián Carrillo was a truly great composer, not just some obscure theorist who lived in an ivory tower spinning odd theories for the edification of other ivory tower academics. His music has feeling and emotion to spare; it is illuminating and moving, even at its most tonally slithery. He was so solidly grounded in the compositional framework of the late 19th century that it would have been impossible for him to write music that was purely a mathematical exercise. Perhaps the two strongest examples of this are the 1939 Violin Sonata (mostly chromatic) and the 1941 Triple Concerto, neither of which rely that strongly on microtones although elements of that style can clearly be heard. Indeed, in this work he developed a technique that I’ve never heard any other composer accomplish: giving each of the three solo instruments cadenzas to play in the third movement, then having them use elements of those cadenzas in a sort of contrapuntal development in the fourth movement. This is living, breathing music which needs to be played, heard and recorded far more often than it is, which is almost never.

The one drawback to the online examples of his art is the fact that few of the performers are identified. I had to rely on the sometimes-sporadic website Discogs in order to find out who the heck was playing much of this music, and so I give the work titles and the performers to you for your edification:

1ª Sonata en Mi menor dedicada a Paganini (1939) – Gabrielle Devries, violinist

First String Quartet (1924) – Quatour Villers

Horizontes for Cello, Harp & Orchestra (1947) – Reine Flachot, cellist; Monique Rollin, harpist; Gabrielle Devries, violinist; Orchestre de Concerts Lamoureaux, conducted by Carrillo

Preludio a Colon (revised version) – Reine Flachot, quarter-tone cellist; Quatour Villers; Annick Simon, soprano

Balbuceos – Bernard Flavigny, pianist; Orchestre de Concerts Lamoureaux, conducted by Carrillo

First Concerto for Cello in quarter and eight tones – Reine Flachot, quarter-tone cellist; Orchestre de Concerts Lamoureaux, conducted by Carrillo (available for streaming in 3 parts, beginning here)

Cromometrofonía – Oscar Vargas Leal & David Espejo y Avillas, microtonal harpists

(available for streaming in 3 parts beginning here)

Happy listening!

—© 2018 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter or Facebook @Artmusiclounge