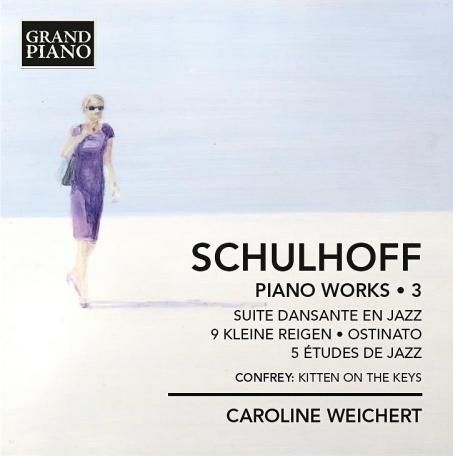

Schulhoff PIANO WORKS, Vol. 3 / Suite Dansante en Jazz; 9 Kleine Reigen; Ostinato; 5 Etudes de Jazz. Confrey: Kitten on the Keys / Caroline Weichert, pianist / Grand Piano GP723

It was in 2003 that British pianist Kathryn Stott issued the first CD devoted entirely to the piano works of Erwin (sometimes Ervin) Schulhoff (1897-1942). Prior to that, there had been several discs on which a work or two by Schulhoff, mostly chamber and orchestral music, had been issued (the only all-Schulhoff CDs were the one of Symphonies Nos. 1-3 conducted by George Albrecht on CPO and two volumes of pieces played by the ever-adventurous Ebony Band on Channel Classics), very little of it suggesting the wild, jazz-influenced piano music that Stott unleashed on us. Now, here is Vol. 3 of a continuing series of Schulhoff’s piano music played by the extraordinary German pianist Caroline Weichert.

Caroline Weichert

To say that Weichert has the full measure of Schulhoff’s quirky music would be an understatement. I have the highest respect for Stott, since her performances had almost nothing to be compared to and she gave them her all, but by and large her sense of rhythm was that of ragtime. While it is true that Schulhoff’s music was indeed based on ragtime, and a white, commercial form of early jazz that arose from ragtime, I must say that Weichert gives every piece that Stott herself recorded even more of a jazz swagger. Of course, this only includes (so far) the Suite Dansante en Jazz and the 5 Etudes de Jazz. Weichert’s series has yet to tackle the Piano Sonata No. 1, the Second Suite for Piano, the 11 Variations of 1921 or Hot Music: 10 Syncopated Etudes (1928), and Weichert’s present CD includes two piano works not jazz-influenced at all, the 9 Kleine Reigen and the six-part Ostinato. Not everything Schulhoff wrote was jazz-inflected, but it did run like a silver thread through most of his piano music from 1919 to around 1931. In Vol. 1 of her series, Weichert included the quirky, early 5 Pittoresken which includes a completely silent movement titled “In futurum” (thus beating John Cage to the punch by 40 years) and an extraordinarily delightful six-part suite titled Esquisses de Jazz.

Erwin Schulhoff

I discussed Schulhoff in some detail in my book, From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed history of the intersection of classical music and jazz (Chapter III, pp. 47-48), explaining that although he based his concept of “jazz” on “hot dance music” of the time, and in fact never visited America where he could have heard actual, real, African-American jazz direct from the source—as did Darius Milhaud and Maurice Ravel—he made some startling inroads into the codification of jazz dance rhythms and a feeling of improvisation in music that was very thorough-composed and in places extraordinarily challenging for the pianist. The fifth of his 5 Etudes de Jazz, in fact, is titled “Toccata sur le shimmy ‘Kitten on the Keys’ de Zez Confrey,” is one of the most virtuosic and difficult pieces of its day, a real showpiece which both Stott and Weichert play with tremendous zest and a feeling of real discovery, but only Weichert also gives us Zez Confrey’s original piece, which I would wager that 99% of modern-day listeners have never heard. Kitten on the Keys was a tremendous hit in its day, but moreso in terms of sheet music sales than records; one must remember that, even as late as the early 1930s, recordings were meant to sell sheet music, not the other way around. It wasn’t really until the advent of the Swing Era and the coming of jukeboxes and radio DJs like Martin Block that records as such became paramount in importance in and of themselves, particularly

Zez Confrey

jazz recordings where the improvisation was the composition. All of which is a roundabout way of saying that Confrey only made one piano solo recording of his most famous composition, and that was for Edison, whose vertical-cut records could only be played on special phonographs designed for that type of record. As a result, most people either heard it played by their talented cousin or sibling on the keyboard from the sheet music or from Confrey’s orchestral recording for Victor (made May 18, 1922, and sounding like some idiotic silent comedy tune, complete with slap-tongue reeds, though Confrey does play a bit of it on the keyboard in between this nonsense). And yet—hold your breath as you read this—this was probably the recording that Schulhoff heard and which inspired his wild fantasy!

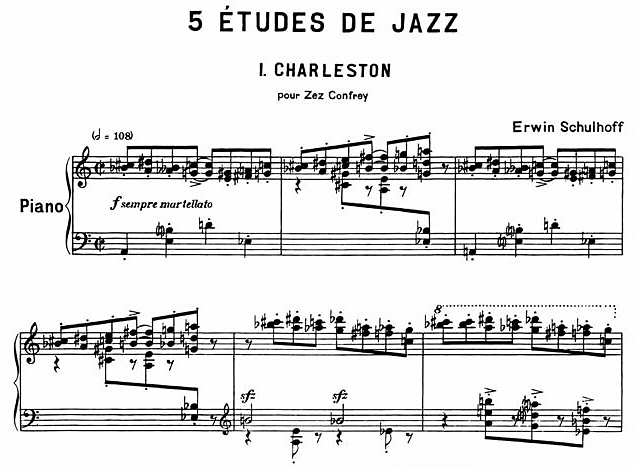

Indeed, as you look through the titles of the individual pieces within his “jazz” suites, you will find—in addition to such expected titles as “Charleston,” “Tempo di Fox,” “Jazz-Like,” “Tempo di Rag,” “Blues,” “Stomp” and “Shimmy-Jazz”—such incongruous (for jazz) titles as “Tango” (lots of tangos…apparently, Schulhoff didn’t hear much difference between jazz syncopation and tango syncopation, though they are worlds apart), “Boston” (I haven’t a clue what this refers to…there certainly wasn’t much real jazz heard from Boston until the Swing Era), “Waltz” (there wasn’t a single waltz in the entire jazz world until Fats Waller wrote his Jitterbug Waltz in the late ‘30s) and “Chansons” (apparently Schulhoff confused sultry French singers with cigarette butts dangling from their lips with the blues). Well, bless him, at least he tried, but to get an indication of just how Eurocentric his worldview was one should note the dedications of each of the five Etudes de Jazz—not one naming a real jazz musician. “Charleston” is for Zez Confrey, “Blues” for Paul Whiteman (yeah, man, there was one hip blues musician!), “Chanson” for Robert Stolz (the German operetta composer), “Tango” for Eduard Künnecke (another German operetta composer) and the “Toccata on ‘Kitten on the Keys’” for Alfred Baresel, the only name among the five involved with real jazz, although probably the least well-known today. Baresel was, in fact, one of the founders of the German jazz movement and the very first German music critic to take jazz seriously. His first book on jazz, published in 1926, was later on the Nazis’ banned book list as an example of “Degenerate Art.”

The other two works on this CD, the 9 Kleine Reigen and Ostinato, are charming, fully classical piano works in Schulhoff’s mature style, and it is interesting that Weichert plays them with a different “feel.” She is certainly a very clever and gifted musician who approaches her work with a rare combination of curiosity and seriousness. I noted that her performances of the Suite Dansante and 5 Etudes run longer than Stott’s, but in almost each case the individual movements have more of a jazz “swagger” at the slower tempos. My sole complaint of this recital was that I found her performance of Confrey’s Kitten on the Keys to be somewhat too slow, which hurts the music’s stated intention of imitating a kitten walking on the keys of a piano. (There’s a marvelous photo going viral right now that shows a cat walking across piano keys who says, “I don’t play piano…I play FORTE!”)

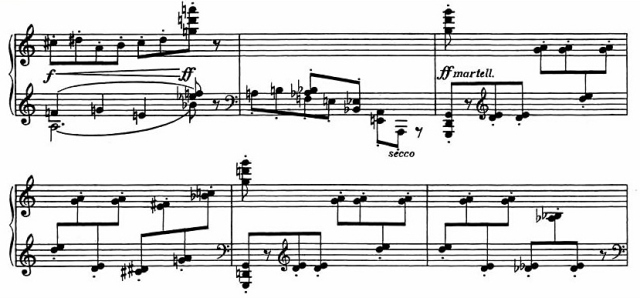

Breaking the music down to essentials, the jazz-based works often skitter along using a beat like this:

—which isn’t really a jazz beat per se, but a ragtime beat, and in fact a rather strict ragtime beat without much modification. Scott Joplin varied the beat far more than this in most of his classic rags, but to Schulhoff’s defense this was a typical beat played by many white, unswinging jazz bands, which were probably all Schulhoff heard. In fact—and I have no direct evidence on this but am going by my decades of knowledge and experience—I’d wager that most of the music Schulhoff heard and thought was “jazz” was probably played by German bands, many of which played exactly this rhythm in many of their 1920s recordings.

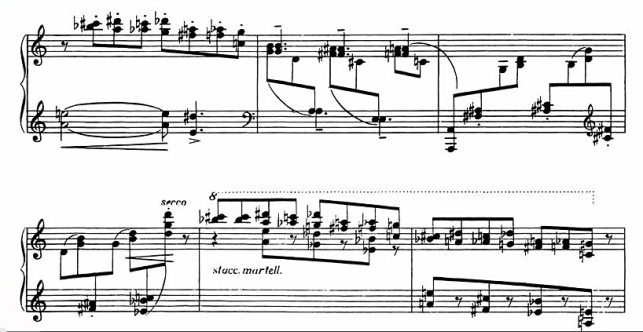

But Schulhoff’s innovations—and, in exchange, his contribution back to jazz—was never in rhythm but in harmonic movement. Looking over the first several bars of the “Charleston” from the 5 Etudes de Jazz, for instance, we clearly see a piece that begins generally in C major immediately altered via advanced chord positions and tone clusters, then shot in the fifth and sixth bars into an upper stratosphere that wasn’t even touched upon by any jazz pianist until the arrival of Art Tatum on the international scene in 1933, and then only sporadically. This type of harmonic language really didn’t come into jazz on a semi-regular basis until fairly late in the bebop era, i.e., in the late-1940s recordings of the Dave Brubeck Octet, or regularly until the late 1950s with the arrival of such avant-garde pianists as Martial Solal and Cecil Taylor—and Taylor never used this sort of harmonic language with the same sort of rigorous structural integrity that Schulhoff does here:

Schulhoff may also be viewed as a missing link (so to speak) between, say, the ragtime pianists and such jazz-classical composers as Alexander Tsfasman (1930s-1950s) and Nikolai Kapustin (1960s-present), and his music is fascinating and vital. I look forward to Weichert’s future entries in this Schulhoff series!

— © 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Read my book: From Baroque to Bop: An extended and detailed history of the intersection of jazz and classical music

Great article! I’m thrilled to see any pixels at all celebrating Schulhoff’s endlessly fascinating compositions.

Incidentally, you may want to investigate the interpretations of Czech pianist Tomáš Víšek if you haven’t already. He has a number of discs on the Supraphon label and covers most if not all of Schulhoff’s solo piano work. I really like his readings, which seem to bring a rubato sensibility (without sounding mannered) to syncopations in the pieces that can end up sounding corny in the wrong hands. As a result, they really underscore the stunning harmonic conception that, as you point out, Schulhoff innovated and rigorously explored decades before anyone else.

Looking forward to hearing Weichert’s take!

LikeLike

Your style is so unique in comparison to other folks

I’ve read stuff from. Thanks for posting when you

have the opportunity, Guess I’ll just book mark this page.

LikeLike