NØRGÄRD: Gilgamesh / Björn Haugan, ten (Gilgamesh); Helge Lannerback, bar (Enkido); Britt-Marie Aruhn, sop (Aruru); Jørgen Hviid, ten (Huwawa); Ranveig Eckhoff, sop (Siduri); Merete Bækkelund, alto (Ishtar); Birger Eriksson, bar (Utnapishtim); Solwig Grippe, alto (Utnapishtim’s mother); Rolf Leanderson, bar (Priest); Monika Hagelin, sop (Citizen 1); Eva Larsson, sop (Citizen 2); Erik Backman, ten (Citizen 3); Dieter Schlee, bass (Citizen 4); Karl-Robert Lindgren, bass-bar (Citizen 5); Richard Berg, bar (Citizen 6); Swedish Radio Chorus & Orch.; Tamas Vetö, cond / Voyage into the Golden Screen/ Danish Radio Symphony Orch.; Oliver Knussen, cond / Dacapo DCCD 9001

Here’s a freaky blast from the past that I’ve just discovered: Per Nørgård’s 1973 “opera-ballet” Gilgamesh, based on the old Norse legend of the creation of the world, paired with his 1986 orchestral piece Voyage into the Golden Screen in which he combines “western rationalism” with “eastern mysticism.”

Gilgamesh is not an opera (ballet) that has ever been performed, even in Denmark, with any regularity because it, too, is freaky. It’s not a “staged” opera meant to be played to an audience, but a theater-in-the-round total immersion piece. To quote the booklet:

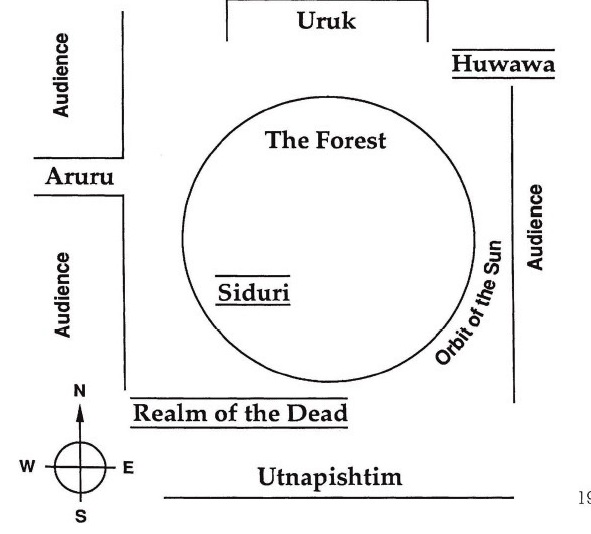

The opera is not divided into acts, and unlike a traditional opera the action is not played on a stage accompanied by an orchestra, with the spectators arranged in the auditorium. Instead, the setting is a rectangular room, the audience seated along two long sides, and some of the performers – musicians and singers alike – placed at certain permanent positions in the room, while other performers are acting on various parts of the floor. All the musicians are costumed so that the barrier between dramatic action on one hand and music accompaniment on the other is eliminated. Thus all those present in the room form part of the opera’s synthesis of musical motion and artistic stylization…even the conductor, who in a traditional opera must have a stationary position…is moving around in Gilgamesh.

Here’s their illustration of the performing space:

But if you think that’s freaky, wait until you hear the music, which clearly has a very strong influence from Eastern sounds and, for want of a better term, ancient music. The socre is the aural equivalent of old Nordic runes. Nørgård bases much of his music on number sequences, particularly the infinity series for serializing melody, harmony, and rhythm in musical composition. The method takes its name from the endlessly self-similar nature of the resulting musical material, comparable to fractal geometry. That sounds pretty intimidating, but when you listen to the actual music he turned out, it sounds relatively tonal and melodic, albeit using complex rhythms and melodic “cells” that are repeated later in the work with a different rhythm and/or different orchestration, thus producing an entirely different effect. It also has the aspect of what I would call “space music,” although he often increases the volume to emphasize dramatic moments.

Being based on cells and number sequences, Nørgård’s music is much more complex than minimalism, although there are repeated cells and motifs throughout, particularly in CD 1/band 10. There are also only occasional solo lines by the characters, yet the chorus includes several operatic soloists of high quality which gives the music a consistent high quality of pitch and execution. Remember, even in the 1980s we still were not overloaded with wobbly, infirm “operatic” voices like we are now. You had to sing steadily and in tune back then.

Nørgård describes this work in his own words:

the words – mostly taken from the epic – do not play the leading part except in a few passages. Then, these passages have been composed with the utmost regard for the comprehensibility of the text. In the remaining – and greater – part of the opera, the words are significant to a certain extent only, but beyond this they function as phonetic elements (e.g. URUKS MUR (Uruk’s wall) with all its U- and R-sounds ), or form a symbolic incantation.

This, then, is a surround-sound chamber opera, meant to be experienced in its odd performance space as a total immersion, as if learning a foreign language but only having an hour and 40 minutes to do so. It’s a psychological teaser that has no meaning beyond the listening and feeling experience. Thus although you are missing the physical presence of the singers in costume and the added dimension of the dance, listening at home to this work on your stereo speakers is a pretty good substitute for being there.

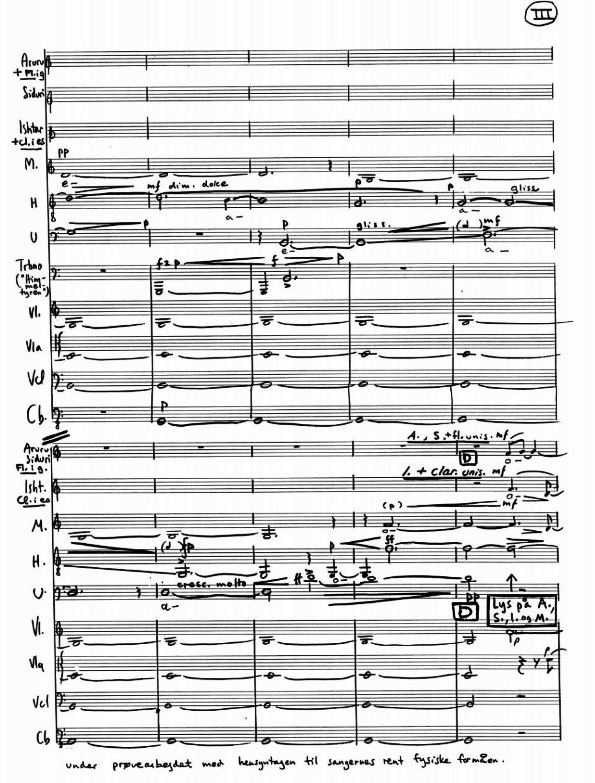

Needless to say, since this work was designed to play in a small room, the orchestration is light: a few strings, brass and winds with percussion (primarily the bass drum). You rarely hear more than a few instruments at any one time; I would guess that the full orchestra probably numbers no more than 25 or 30 players. One might also think that some of the music came from ancient folk music, but it didn’t and, with the continually shifting rhythms, couldn’t possibly have been absorbed by ancient peoples. Here are two pages of the score to illustrate how he put it together:

Keeping the score harmonically simple means that much of the music uses “regular” chord spacing, thirds, fourths and fifths. Nørgård purposely avoids extended chords or, in fact, any harmonic friction in order to make the score accessible to average listeners, yet there are moments where a soloist sings a line or two that runs against the harmonic grain, at least for short periods of time. On CD 1, track 11, Nørgård has three solo voices playing against one another simultaneously, with the chorus and orchestra dropping out. Throughout the opera, the singers must have absolutely perfect pitch in order to make it work. Even slight pitch deviations would upset the entire balance of the music. One thing’s for sure, though. Drink some vodka, turn on the strobe lights and put this record on, and you won’t need LSD to get high.

On CD 2, we hear more advanced harmonies—at least, some extended chords—which add to the otherworldly effect of the opera.

The filler piece, Voyage Into the Silver Screen, is a similarly offbeat instrumental work which includes harmonicas conducted by the late, lamented Oliver Knussen. This, too, is spacey music combining Western rationalism with Eastern mysticism, and I can hear why Nørgård feel so all alone. You don’t hear many Eastern musicians playing harmonicas. (Bob Dylan and John Sebastian are NOT popular in the Middle East.) This piece consists mostly of very long lines, which become interwoven and more complex harmonically as the piece goes along. Once again, there are interesting percussion outbursts when you least expect them.

Both works were recorded at live performances, but there are just two or three tiny sounds in Gilgamesh from performer movement or audience sniffles, and just a cough or two in Voyage. I heartily recommend that you discover these pieces; you won’t be disappointed.

—© 2024 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Facebook (as Monique Musique)

Check out the books on my blog…they’re worth reading, trust me!

Pingback: Per Nørgård’s “Gilgamesh” – MobsterTiger