A friend of mine sent me a CD which included a large number of recordings, most of them acoustic, of rare recordings from the first 34 years of the 20th century. Several of them impressed me, but none quite as forcibly as a Belgian tenor I’d never heard of, Laurent Swolfs. Although he was “only” singing a song, Flégier’s Le beau rêve, the voice absolutely bowled me over. Who WAS this guy? Well, as we shall see, except for a brief sojourn in Vienna, he restricted his career to Belgium, France and Holland, and although he recorded extensively between 1906 and 1924, 193 sides in all (21 were unissued, destroyed takes), he played “record tag” with a number of labels, some of them obscure like Reneyphone and Disque du Saphir, and even when he recorded for known labels like Odeon, Pathé or HMV, they only had local distribution. No one had ever issued an entire album of his recordings; the closest any of them came was Malibran Records, which put six tracks by him on a CD of Belgian and Flemish singers. You can view his entire discography by clicking HERE.

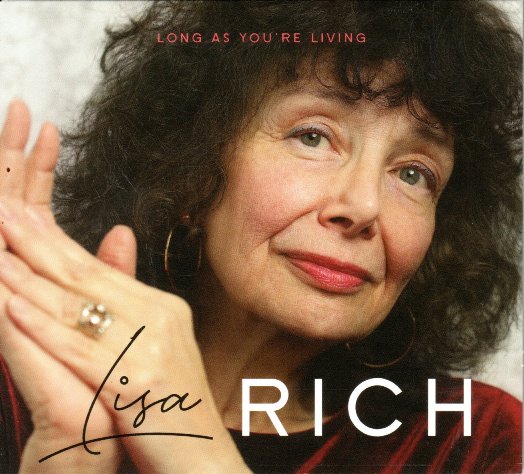

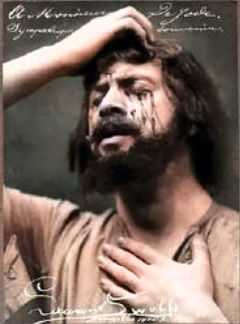

Swolfs as Tristan

So I began digging. I found eight other recordings on YouTube, one or two on the Internet Archive, and a surprise cache on another site which finally included a couple of Wagner arias. Yet this was a man who sang a wide gamut of roles, from such lyric parts as Wilhelm Meister in Mignon, the title role in Werther etc. to Canio in Pagliacci, Enée in Le Prise du Troie (the first part of Berlioz’ Les Troyens) and all of the Wagner roles, which makes him the only other tenor besides Lauritz Melchior to sing the full range of Wagner’s approved operas. Yet frustratingly, most of his 123 recordings were of songs (he was particularly fond of Keurvels’ Wiegenliedje)! Some of these were really rubbish, like Ma Curly-Headed Baby,

Swolfs as Werther

and for some ungodly reason he made three different versions of “Cantique de Noel” (“O Holy Night”). He also recorded two different takes of “Chanson Hindou,“ but NOT the Rimsky-Korsakov aria; it was written by Bemberg. Like Caruso, he recorded a version of Handel’s “Ombra mai fu” from Xerxes at his last recording session (1924). He was also loath to record duets. The only ones he made were Faure’s “Crucifix” with a Dutch bass named Huylebroeck for Parlophone c. 1912 and three duets (one each from Mirielle, Faust, and Carmen) with a French soprano named Berthe d’Anory for Reneyphone/Polydor in 1922 or ’23. Apparently he had a thing for doing songs or, like Jon Vickers, he hated “ripping” arias and duets out of context to record as a single item, but sooner or later I came up with 16 sides—technically, enough to fill out a full LP back in Ye Olde Days.

Enée in La Prise de Troie

Here is what I learned about him by searching online. Born in Ghent in 1868, Swolfs studied singing in Antwerp and Brussels with Désiré Demest, among others, but it was essentially Demest who settled his voice for life. Demest was also the teacher of Fernand Ansseau, Armand Crabbe and Hector Dufranne, all first-rate singers. Swolfs began his career as a concert singer, then made his debut in 1901 at the Opera House of Antwerp as Max in Der Freischütz. In 1903 he was engaged by the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels, where he had a successful career for more than 20 years. In 1906 he sang, astonishingly, the first part of Berlioz’ Les Troyens (La prise de Troie) in Brussels with Mme. Charles-Mazarin and Sylvain Dupuis (11 performances), then later the same season created the role of Herod in the Belgian premiere of Strauss’ Salome (17 performances), and in the 1908-09 season he worked at the Opera House of Lyon. In 1908, conductor-composer Felix Weingartner, who heard him in Antwerp, brought Swolfs to the Vienna Court Opera to create the leading role in Weingartner’s opera Genesius. While in Vienna he also sang the title roles in Lohengrin and Samson et Dalila. In 1910 he had a huge success at the Paris Grand Opéra as Siegmund and as Samson. In 1911 he sang at the Opéra-Comique of Paris in the premiere of Albéric Magnard’s opera Bérénice. In 1913, he appeared there as Loge in Rheingold and made guest appearance at the Opera House of Nice. After the First World War, he became a successor to Ernest van Dyck as a professor at the Brussels Conservatoire. From 1923-25 he was at the same time the artistic manager of the Opera House of Antwerp and continued singing. After his retirement he lived in Ghent, and near the end of his life he became blind.

Young Swolfs (pre-facial hair)

The one thing everyone agreed on was that he had a powerfully controlled and metallically shining voice. What I found most interesting about him were two things: first, that he took most of his high notes in head voice or voix mixte, much like the French fort tenor Léon Escalaïs, and second, that he had almost inexhaustible lung power which allowed him to sustain phrases for an incredibly long span. In addition to these assets, he was also a sensitive and musically creative singer who could shade the voice and color it effectively, especially in those songs. In short, his is the kind of singing that should be a model today for virtually any tenor attempting to sing heroic roles, but of course he isn’t. Most modern dramatic tenors bluster and bellow as if they were trying to blow down the third little pig’s house of bricks and not doing so. They have vocal strain, wobble, uneven registers and all sorts of vocal flaws which would never have allowed them to get beyond comprimario roles in the old days. But of course we can’t just blame the singers themselves; all of them had teachers, thus it is to the teaching methods of today that we must lay 90% of the blame. Lauritz Melchior, Wolfgang Windgassen, James King and Jon Vickers all sang with steady tonal emission well into their 60s. There is really no excuse for the garbage we hear coming out of modern-day dramatic tenors. Even José Cura, who started singing professionally rather late and went on a bit too long, had some marvelous years when he didn’t have half the problems we hear out of such tenors today.

Swolfs as Dalibor, 1902

But to return to Swolfs, one really must hear him to believe him. Like Escalaïs, Caruso, Slezak and a very few others, his voice sounded remarkably natural even on acoustics, and I would go so far as to say, based on the cross-section of records I’ve heard spanning 14 years, he was even more consistent than the latter two. Putting it plainly, Laurent Swolfs was a singing machine, but one with a heart and a mind. What sounds so easy on the records must have cost him untold hours of practice and discipline to create and, more importantly, maintain.

Curiously, there is almost nothing available online about his personal life. We don’t even know if he was married or had children, and nowhere can you find an inkling about his personality. We know at least a little bit about his more famous Dutch contemporary, Jacques Urlus, than we do about him. Of course it is his singing that principally engages us, but it would be interesting to know if he was a lover of poetry since his song interpretations are so outstanding.

A cross-section of Swolfs’ record labels

Swolfs as Samson

I have uploaded most of my Swolfs recordings, cleaned up as best I could, to the Internet Archive, and at a page on the Historical Tenors website you can hear five more recordings (not cleaned up) including two of his Wagner excerpts, “Am stillen herd” from Die Meistersinger and the “Wintersturme” from Die Walküre. Yet all of this information put together does not indicate the breadth of Swolfs’ repertoire, which included Dalibor, Der Evangelimann, Der Freischütz, La damnation de Faust, Hérodiade, Elektra, and even one of the “outside” Wagner operas, Feuersnot—yet oddly, it did not include the French operas from which he recorded the duets with Mme. d’Anory!

In any event, Laurent Swolfs is clearly a tenor you should investigate if you are a lover of truly great singing. As I wrote to my friend, he has brought several excellent but neglected singers to my attention over the years (such as mezzo-soprano Susanne Brohly), but among tenors Swolfs is clearly the greatest artist and voice of them all.

—© 2024 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Facebook (as Monique Musique)

Check out the books on my blog…they’re worth reading, trust me!