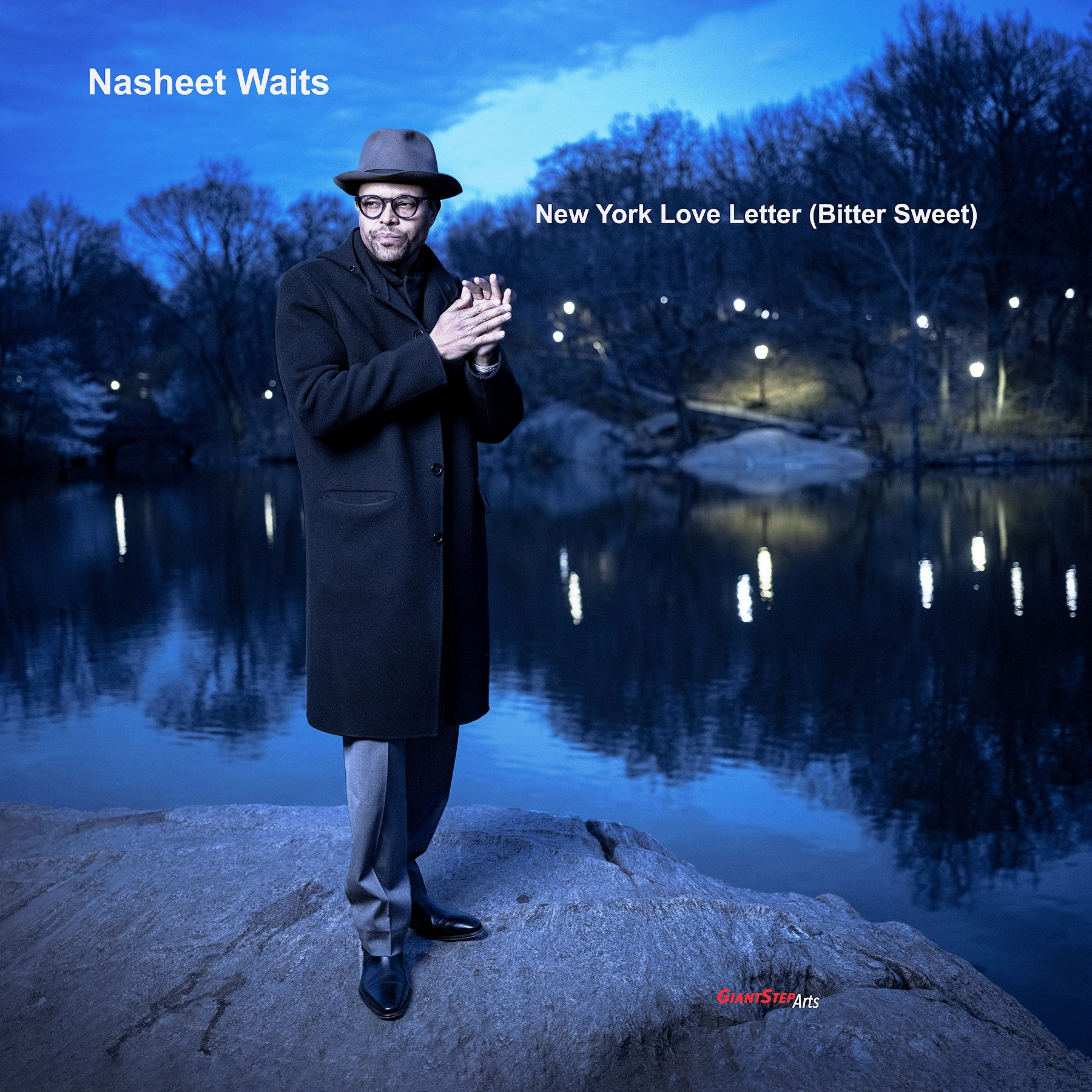

NEW YORK LOVE LETTER (BITTER SWEET) / Snake Stance. Snake Hip Waltz. Moon Child. The Hard Way AW (Waits). Liberia. Central Park West (John Coltrane) / Mark Turner, t-sax; Steve Nelson, vib; Rashaan Carter, bs; Nasheet Waits, dm / Giant Step Arts GSA 14

Scheduled for release June 28, this album spotlights versatile drummer Nasheet Waits, who Ted Panken of Jazziz named the “First call…for multiple bandleaders…who want a drummer to render a 360-degree range of styles and authoritative execution, high musicality, imaginative invention and inflamed-soul spirit.” This particular quartet also includes tenor saxophonist Mark Turner, whose own Giant Step Arts CD I gave a good review a while back, as well as Steve Nelson on vibes and Rashaan Carter on bass, all playing compositions by Waits himself.

My regular readers are well aware how much I’ve complained about the paucity of really interesting original jazz compositions nowadays. With a few exceptions (among them Moppa Elliot, Silke Eberhard and Jungsun Choi), the majority of contemporary “jazz composers” just write what I hear as a few indistinct musical gestures, hastily stitched together to make a “theme” which is really no theme at all. On many such album, the only interest is in the improvisations.

Not so here. Waits is a musician through and through, not “just” a drummer, and these compositions actually have meat on their bones. Although not super-tuneful (of course they don’t have to be), they are at least real themes with good harmonic movement. In fact, one of the things I liked about them was that the harmony moves with the melodic line, and in form and shape they resemble the music of Thelonious Monk without aping it. You will never hear a “real” Monk theme in a Waits composition, but he comes close enough to at least evoke that great master of modern jazz.

In fact, what I heard on this recording were fully integrated jazz compositions in which the structure is actually more important than the solos, good as they are. In a way, this harks all the way back to such pioneer jazz composers as Jelly Roll Morton and Bill Challis, who found ways to integrate the strengths and minimize the weaknesses of the individual musicians in the bands they wrote for, producing what were then real rarities, fully integrated conceptual jazz. Monk did the same thing in his early period, 1947-52, but later Monk recordings tended to sound more like convivial jam sessions with rare exceptions (like the Thelonious Monk Orchestra’s live set at Town Hall in New York).

None of which is meant to belittle the contributions of these soloists, particularly Turner whose solo on Snake Hip Waltz is one of the greatest and most prodigious solos I’ve heard from any modern-day tenor saxist, but even Nelson and especially Carter play solos on this track (and the others) that are mind-boggling in their originality. As for Waits, yes, he does tend to dominate certain passages within each piece, but like the very best drummers of the past (Dannie Richmond, Jack DeJohnette, Elvin Jones, Joe Morello, etc.), his playing is musical, Never once did I get the feeling that what he was playing diverted too far away from the basic pulse of each piece or was trying to dominate the ensemble just to show off. Yet I do think that, whether purposely or accidentally, that his drums were over-recorded. The reason I say that is that, in the very soft and intimate Moon Child (a really creative as well as lovely theme played primarily by Nelson on the vibes), Waits sticks mostly to brushes, and brushes should never really dominate the sound of a quartet…yet they do so here, and personally I don’t believe that Waits was the one who insisted on this kind of microphone set-up. A foot or two further back from the mike, and he would have sounded just right.

Between the excellence of these compositions and the excellence of the solo playing, I found myself mesmerized from start to finish of this extraordinary set. Although none of this is really “outside” jazz, Turner does stretch “out” occasionally, which makes the listener pay close attention to everything he performs. Small wonder that Waits has praised him for his sensitivity and high musicality. The one really sad thing about this set is that, when you hear the live audience applaud, it sounds as if there were only about 10 people in the audience. Does jazz this good really appeal to that few number of people?

Yet the inspiration engendered by this quartet transcends whatever audience they had; this is a group that evidently plays for themselves, to spur and encourage each other to the best they can do. You can hear this particularly in The Hard Way AW, one of Waits’ more adventurous compositions with its juxtaposition of different themes in different rhythms, including one passage using quarter note triplets in each bar. This is also one of those tracks on which Turner flies into the musical ionosphere with some edgy outside playing, to which Waits responds with one of his finest drum solos on this record. Although he generates a lot of power on his drums, he does not steamroll his musicians the way Art Blakey did. Rather, he is one of those rare beings, a real percussion artist like Vic Berton, Chick Webb, Morello and Elvin Jones, who creates solos with a large amount of rhythmic diversity and subtlety. He is a colorist on the percussion, drawing as much out of his instrument as Turner does on the tenor sax.

Intentionally or not, the impression one gets from this group as the CD continues is that Turner and Waits are the real musical leaders. Both Nelson and Carter continue to be very good, both in the ensemble and in their solo spots, but in the end it is Turner and Waits who mesmerize you most often.

Clearly the strangest piece on the album is John Coltrane’s Liberia, its opening crafted by Carter playing his bass with the bow on the very edge of the strings to create an eerie sound. Eventually he returns to playing plucked bass with the vibes mixed in. At one point—and I may be wrong—it sounded to me as if a portion of the performance was spliced out of the master tape (perhaps it didn’t come off as well as the musicians would have liked). When Turner enters, the tempo gradually increases and Waits’ drums become busier, but in a “dancing” way. His playing is light and airy, not heavy, and surprisingly the tempo increases once again into a fast swing beat, with Carter driving the group from the bass. Turner continues to be the dominant soloist, however, and on this track Nelson rather recedes into the background, yet what he does play fits in. Despite his excellent technique Carter isn’t a flashy bass soloist. What he plays is musically “meaty” and, again, fits into the overall concept of the piece

We end with a ballad, and (for once) a really good one, Coltrane’s Central Park West, which has almost an Autumn in New York kind of vibe. Waits is again on brushes (and a little more recessed than previously) with occasional soft press rolls and cymbal work as Palmer plays very sensuous tenor and Nelson adds a lovely vibes solo, but again it is Palmer who dominates one’s attention. Overall, this is an extraordinary set and clearly one of the finest jazz releases of the year to date.

—© 2024 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Facebook (as Monique Musique)

Check out the books on my blog…they’re worth reading, trust me!

Pingback: Nasheet Waits’ New York Love Letter – MobsterTiger