SPONTINI: Olimpie / Karina Gauvin, sop (Olimpie); Kate Aldrich, mez (Statira); Mathias Vidal, ten (Cassandre); Josef Wagner, bar (Antigone); Patrick Bolleire, bs (L’Hiérophante/ Un Prêtre); Philippe Souvage, bs (Hermas); Flemish Radio Chorus; Le Cercle de l’Harmonie; Jérémie Rhorer, cond / Bru Zane BZ1035 (live: Paris, June 3, 2016)

SPONTINI: Olimpie / Karina Gauvin, sop (Olimpie); Kate Aldrich, mez (Statira); Mathias Vidal, ten (Cassandre); Josef Wagner, bar (Antigone); Patrick Bolleire, bs (L’Hiérophante/ Un Prêtre); Philippe Souvage, bs (Hermas); Flemish Radio Chorus; Le Cercle de l’Harmonie; Jérémie Rhorer, cond / Bru Zane BZ1035 (live: Paris, June 3, 2016)

Gasparo Spontini’s operas, several of them not only brilliant but groundbreaking, remain maddeningly on the outskirts of the standard repertoire. Despite the enduring popularity of Maria Callas’ savagely abridged 1954 live performance of La Vestale, neither it, Fernando Cortez, Olimpie nor Agnese di Hohenstaufen are in the standard repertoire of any opera house in the world—yet we continue to get endless garbage from Rossini and Donizetti year in and year out, including the latter’s banal “Queen trilogy.”

Why this is lies more in the nature of the music than in its high quality. Although Spontini introduced an Italian lyricism to the Gluck tradition, he followed his idol in writing continuous scenes in which arias, duos, choruses and massed ensembles followed one another with little breaks for applause or garish high notes for the singers to hang onto. He was writing musical drama, not pop garbage, and most operagoers want their rum-tum-tum tunes, with appropriate breaks to scream loudly in the climactic high notes. Spontini doesn’t give them that, and alas, his name does not have the magical allure of Gluck himself. Although some of the choral writing is typical of Italian opera of the time, most of it is quite moving and dramatic (hear the opening scene of Act II) in the style of Gluck, giving it far more importance than Donizetti or early Verdi.

This is only the second studio recording of Olimpie, the first being Gerd Albrecht’s fine 1987 version for Orfeo. In that recording, he had a pretty stellar international cast, but only one of the singers—basso George Fortune as the Hierophant—had really decent French diction. The others, which included star German spinto soprano Júlia Várady, Italian tenor Franco Tagliavini, Polish mezzo Stefania Toczyska and Varady’s husband, legendary baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, made do with French pronunciation that was approximate at best and, in Várady’s case, almost unintelligible. Yet the recording had good sweep and a sense of drama, thanks to Albrecht’s conducting, and one got a fair idea of the excitement and elegance of this score.

In this performance we get all but two native French-speaking singers, the exceptions being Austrian baritone Josef Wagner as Antigone and American mezzo Kate Aldrich as Statira, and the difference is almost startling. The words emerge not only with greater clarity but, much to my surprise, an even greater sense of theater…but then again, this recording stems from a live concert performance, not a sterile studio run-through.

The plot, adapted from a 1764 work by Voltaire, mixes up Greek legend with a myth about Alexander the Great. From Wikipedia:

Act 1

The square in front of the Temple of Diana

Antigone, King of a part of Asia, and Cassandre, King of Macedon, have been implicated in Alexander’s murder. They have also been at war with one another but are now ready to be reconciled. A new obstacle to peace arises in the form of the slave girl Aménais, whom both the kings are in love with. In reality, Aménais is Alexander the Great’s daughter, Olimpie, in disguise. [Ed. Note: This must have been news to Alexander, since he was gay, but apparently they didn’t know or believe this in 1819.] Statira, Alexander’s widow [hardy har har!] and Olimpie’s mother, has also assumed the guise of the priestess Arzane. She denounces the proposed marriage between “Aménais” and Cassandre, accusing the latter of Alexander’s murder.

Act 2

Statira and Olimpie reveal their true identities to one another and to Cassandre. Olimpie defends Cassandre against Statira’s accusations, claiming that he once saved her life. Statira is unconvinced and is still intent on revenge with the help of Antigone and his army.

Act 3

Olimpie is divided between her love for Cassandre and her duty to her mother. The troops of Cassandre and Antigone clash and Antigone is mortally wounded. Before dying he confesses he was responsible for the death of Alexander, not Cassandre. Cassandre and Olimpie are now free to marry.

[In the original 1819 Paris version, Cassander is the murderer of Alexander and after his victory, “Statira stabs herself on stage and, together with Olympia, she is called to the Lord by the spirit of Alexander, who emerges from his grave (in Voltaire’s drama, Olympia marries Antigonus and throws herself into the blazing pyre in a confession of her love for Cassander).]

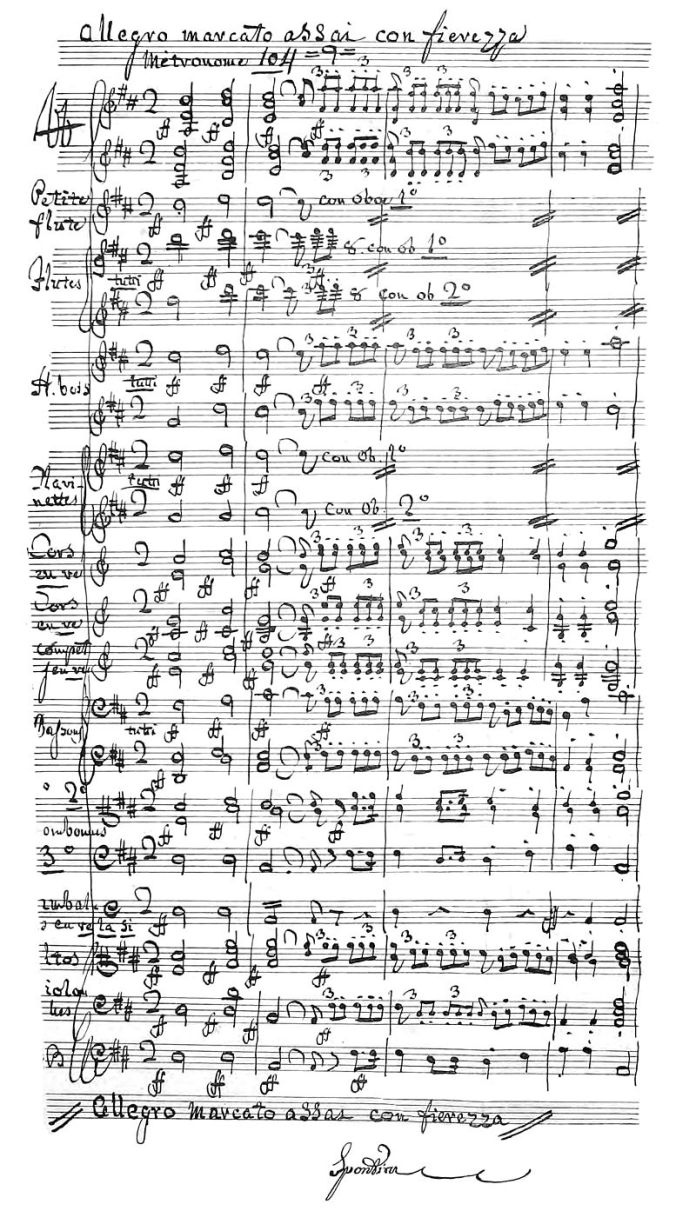

First page of the “Olimpie” overture, with Spontini’s signature at the bottom (credit: Wikipedia)

Spontini’s score sounds like a cross between Berlioz and near-mid-period Verdi, but his ability to write continuous scenes without the stop-and-go of Verdi before Aida makes all the difference in its high quality. Harmonically, he is primarily tonal but adds some piquant transitions and chromatic passages, and at times will shift keys suddenly and dramatically, i.e. the quick key change between the opening chorus and the entrance of Antigone. I would also suggest that Dick Wagner picked up something from Spontini’s extraordinary ability to write long, continuous scenes without a break, although he often credited Bellini’s La Sonnambula and especially Norma for this idea. But remember, folks, Bellini was writing in the 1830s. Spontini’s La Vestale comes from 1807, Fernando Cortez from 1809 and this gem from 1819. There’s a solo arioso for Cassandre at about the 22-minute mark that ends with him going down at the end, not up, while the orchestra comes roaring in to provide the climax. Donizetti or early Verdi would probably have written a high note for the tenor to belt and milk for all it’s worth while the orchestra roared behind him. One example among many: the Olympie-Statira duet in Act II is far more original, interesting, and less pop-music-oriented than the Norma-Adalgisa duet on Bellini’s opera–and it doesn’t build up to bust-’em-out high notes.

Interestingly, Jérémie Rhorer’s tempi and pacing are almost identical to Albrecht’s. One difference is that his orchestra uses straight-tone strings (which, of course, are NOT historically correct, but modern-day performers don’t really care about this; they’re on a mission to convince us it is), and although Rhorer is a conductor who makes his orchestra sound exciting and vital rather than flaccid and whiny, there are a few moments (particularly in the overture) where the legato string passages lack body. This, however, is the only weakness in an otherwise splendid performance which bristles with life and energy from start to finish while Albrecht’s does not, and in listening it’s evident that much of the brilliant and highly effective orchestral writing had a huge influence on Hector Berlioz, an admitted fan of Spontini (the two composers had a fairly good friendship through Spontini’s later, more difficult years). The other difference is that Rhorer’s brass and winds have much more “bite,” which brings the sound of the music more in line with Berlioz, which is of course the right sort of sound.

On balance, then, I was more than willing to sacrifice a little undernourished string tone (seldom fatal in a Rhorer performance) for the increased power and drama of the overall performance. Time and again I was brought up short by the complete emotional and dramatic involvement of the singers, with pride of place going to the two ladies, Gauvin and Aldrich, Wagner as Antigone and Bolleire as the Hierophant. They bring the libretto to vivid life and keep one on the edge of one’s seat from start to finish. The best way I can put it in words is that the Albrecht performance was more elegant in phrasing but this one is more visceral and dramatic.

Being a live performance, Gauvin is a bit fluttery in her entrance, but she quickly warms up and assumes her normal outstanding singing. I wonder about the size of the voice, however, since all the singers are fairly close-miked and I’ve never heard her live. I would guess that she has a somewhat light lyric soprano voice like Mirella Freni in her early prime, which had carry but wasn’t really huge, but Gauvin also has a wonderful brilliance in her voice that early Freni did not have (her voice was more rounded). Some online critics have complained, however, about the small size of tenor Mathias Vidal in the role of Cassander. I will concede that, in this one role, Franco Tagliavini on the Albrecht set was more appropriate (I did hear Tagliavini in person once, as Arrigo in Verdi’s I Vespri Siciliani, and it was a decent-sized lyric voice with a bit of a cut), but you must remember that French lyric tenors of this era didn’t usually have big voices with a “cut” up top. That didn’t enter the picture until Gilbert-Louis Duprez built up his smallish lyric voice by singing high Bs and Cs from the chest in 1831, thus Vidal’s voice is, in my view, appropriate for the role if perhaps one size smaller than expected. One thing that really impressed me was his ability to sing florid runs and turns easily by letting the voice “ride on the breath” the way singers like Edmond Clement and Louis Cazette did in the early 20th century. You seldom hear singing like this anymore, not even from most native French tenors, thus I was surprised and delighted.

Of the other singers, pride of place goes to Kate Aldrich’s Statira, sung with drama and energy (albeit with a fairly prominent vibrato). She almost comes across as a junior Cassandra in Les Troyens, which is probably what inspired Berlioz to write that part the way he did. But really, all of them are quite good although, after having been spoiled by Fischer-Dieskau’s silken-smooth timbre, I have to admit that Josef Wagner sounds a bit like a German Amonasro, although this, too, is not inappropriate for the role of Antigone, and at least he has a good voice. Everyone else is up to their tasks as well although Bolleire, as the Hierophant, has a bit of unsteadiness in his voice.

In toto, then, this is quite the performance of Olimpie and, despite my few reservations, now the preferred recording of this outstanding opera.

—© 2019 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter (@Artmusiclounge) or Facebook (as Monique Musique)

You have really blow my mind with your knowledge, and the same time straight vocabulary and criticism, about was considered “pop” opera, by some snobs.

I´m no way a fan or somebody with knowledge about opera, justa few things. I´m a historian and a documentary maker. My interest for Alexander the Great brought me here.

It´s a sourprise that the opera is about after Alexander´s Death or assesination ( it was never clear ), but anyway y would give it as much oportunities as it takes to really understand the power and tragedy who comes aling with that character ( even if he´s almost nowhere in the play). The idea of Alexander having a daughter is kind of bizarre. We know that bactrian Roxanna gave him a son, who was murdered along with Roxanne by Cassandros ( funny that here he is a romantic character ). Some say that the daughter of King Darius, Stateira was pregnant with Alexander´s child and that´s why Roxanna killed her. And there´s another hipotesis about a woman named Barcine, who was married with the greek General Memnon who was fighting along the persians against Alexander; and she gave him a son Heracles. But it´s hard to believe that a man who loved so much his friends, dog and horse Bucefalus would “leave” a woman and a son behind. Specially becouse the greatest lack of Alexander was not to have an heir to his empire. And greeks would not accept a half persian king like Alexander IV son of Roxanna. As much as the 600 marriages between macedonians and greeks with persian women were forgotten after Alexander´s death, so his politics of harmony betwen races.

The fact of Alexander gay is used for the people who hated him. We really don´t know and there´s no proof. Not even Homero´s THE ILIAD Aquiles and Patroclus were lovers. But if we want to entertain the idea that Alexander and Hefastion were lovers, we got to put these women. Wich makes Alexander bi-sexual, or pan-sexual if you count Bagoas.

Great comentary, I´m gonna listen this opera over and over again. Is there an opera exlusevly about Alexander?

LikeLike

I know of no opera written exclusively about Alexander the Great. As for the Spontini opera, just relax and remember that librettists were forever fooling around with the real lives of historical figures in those days. Look at Verdi’s “Ballo in Maschera,” in which the gay Swedish king Gustavus is shown at the center of a love triangle with Renato’s wife, Amelia, or the other historical inaccuracies in other operas. “Olympie” is an excellent piece of music drama but one shouldn’t take the history in it too seriously. Giordano’s “Andrea Chenier” is more accurate than most such operas, and even there the real story was played around with.

LikeLike